Posts Tagged ‘Rick Perry’

2014 DFW Smog Report: Good News But Don’t Hang Up the Gas Mask Yet

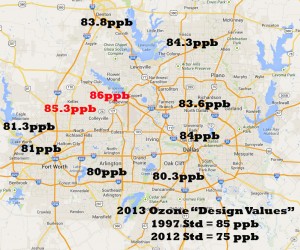

For the first time since DFW began recording its smog levels, the region's three-year running average dipped below the 1997 eight-hour 85 parts per billion (ppb) standard. After years of leveling off at around 86-87, it's dropped to 81 ppb. That's good news.

For the first time since DFW began recording its smog levels, the region's three-year running average dipped below the 1997 eight-hour 85 parts per billion (ppb) standard. After years of leveling off at around 86-87, it's dropped to 81 ppb. That's good news.

DFW's decrease is attributed to 2011's terrible numbers rolling off the board and a wetter, cooler and windier summer than normal these last five months or so. As both drought-ridden 2011 and this year's results demonstrate, weather still plays an extremely critical role in how large or small our smog problem will be. Another summer or two like 2011 could easily put us back over the 1997 standard. More wet and cooler weather could see the decrease continue.

The news would be better except that we were supposed to have originally accomplished this milestone in 2009, then again last year after a second try, according to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

As it is, we still haven't reached the current, more protective 2008 national standard that was revised downward to 75 ppb after a review of the scientific literature.

In January, TCEQ will host a public hearing on its proposed "plan" to EPA to meet that goal that predicts most, but not all DFW monitors will reach 75 ppb by the summer of 2018.

Despite overwhelming evidence that new controls on the Midlothian cement plants and the reduction of gas industry pollution could speed this achievement, TCEQ's new plan contains no new pollution control measures on any major sources of smog polluters – cement kilns, coal plants, gas sources – but instead relies on the federal adoption of a new lower-sulfur gasoline mix for on-road vehicles. Like past proposals by Rick Perry's TCEQ, this one depends solely on the feds to get them into compliance. TCEQ isn't lifting a regulatory finger to help.

And its new plan once again aims high, not low. At last count, there were at least three Tarrant and Denton County monitors that TCEQ admitted would still be above the 75 ppb standard at the end of 2018. "Close enough" is the reply from Austin.

From a public health perspective, it's even worse. Why does the ozone standard keep routinely going down? Because new and better evidence keeps accumulating to show widespread health problems at levels of exposure to smog that were once considered "safe." About every five years, the EPA's scientific advisory committee must assess the evidence and decide if a new standard needs to be enforced to protect public health.

For most of the last ten years, the position of this independent panel of scientists is that the standard should be somewhere between 60 and 70 ppb. They were ignored in 2008. They were ignored in 2011. They once again came to this conclusion last May. What was the evidence that persuaded them? That the current 75 ppb standard for smog causes almost 20% of children in "non-attainment areas" to have asthma attacks, and leads to hundreds of thousands of deaths every year. Cutting the standard to 60 ppb reduces those deaths by 95%. Since the Clean Air Act states the EPA is duty bound to set a smog standard protective of human health, 60 ppb seems to be the threshold level that the current scientific literature says is actually safe for the majority of the population most vulnerable to the impact of bad air. By contrast, a smog level of 70 ppb only reduces those deaths by 50%. (Policy Assessment for the Review of the Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standard, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air and Radiation, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Health and Environmental Impacts Division, Ambient Standards Group, August 2014)

By December 1st, EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy must decide whether to officially recommend a standard in that 60-70 ppb range. It looks as though this time, the EPA might just endorse what the scientists are recommending, although it's unclear whether it'll be the upper or lower part of that range.

So even while the TCEQ is saying it's "close enough" to achieving the 75 ppb standard left over from George W's administration by 2018, the evidence is that level is too high to prevent large public health harms and must be lowered. A lot.

This is why it's so infuriating that the TCEQ is satisfied with getting only "close enough" to a 2008 standard that's about to become obsolete. Austin knows it could demand better air pollution control measures on the market right now that would accelerate the decrease in smog. It knows the pubic health would benefit from requiring such measures. But it's willing to condemn DFW children and others at risk for many more years for the sake of keeping its "business-friendly" reputation.

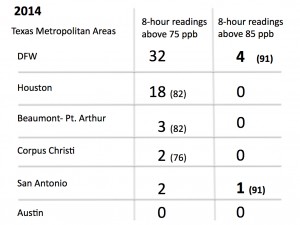

And while this year's slip below the 85 ppb standard is a sign of some progress, it remains true that DFW still has the worst air in Texas – a title we took from Houston years ago. Take a look at the chart summarizing the 2014 ozone season across Texas. Despite the nicer weather, DFW still had almost twice as many readings above 75 ppb as Houston and four above the 85 ppb standard. Houston had no readings above 85. In fact, San Antonio was the only other city to record a level so high – once.

DFW still has a smog problem and all it takes is another hot and dry summer to see it escalate. We need the help more controls on major sources could give us. We need Selective Catalytic Reduction on ALL the Midlothian cement and East Texas coal plants. We need electrification of gas compressors in the Barnett Shale. This should be the message to both the TCEQ and EPA during the public hearing in January.

DFW still has a smog problem and all it takes is another hot and dry summer to see it escalate. We need the help more controls on major sources could give us. We need Selective Catalytic Reduction on ALL the Midlothian cement and East Texas coal plants. We need electrification of gas compressors in the Barnett Shale. This should be the message to both the TCEQ and EPA during the public hearing in January.

DFW smog in 2014: we've met the Clinton era standard for now, on the way to trying to get "close enough" to the W Standard, and still very far from a new Obama standard. Don't hang up the gas mask yet.

The Real Toxic Legacy of Rick Perry? The Thousands of Other Rick Perrys He Leaves In Charge of State Government

When explaining how the powers of state government are distributed under the Texas Constitution, the emphasis is usually on how powerful the Lt. Governor is and how weak the Governor actually is – a leftover from the Confederate backlash to Reconstruction.

When explaining how the powers of state government are distributed under the Texas Constitution, the emphasis is usually on how powerful the Lt. Governor is and how weak the Governor actually is – a leftover from the Confederate backlash to Reconstruction.

But that explanation usually assumes a traditional two-term governor, not one who takes up residency for 14 years.

In the past it was hard for any one Texas governor to put their personal stamp on so many state agencies so deeply because they were out after four to eight years and the terms of the appointments were staggered. Multi-member commissions were a mix of appointees from different administration, representing different government philosophies and parties. This made compromise a necessity.

And then came Rick Perry.

After 14 years, he's not only been able to appoint all the top level decision-makers in all of the state's various agencies and commissions, he's been able to go down two to three layers deep in each bureaucracy and make sure those mid-level officeholders reflect the same views. Compromise is no longer necessary. Through this process, he's assembled more power than perhaps any other Texas governor in history.

Even if Wendy Davis were to win next month, it would take many years to replace Perry's choices for all of the state agencies that affect Texans on a daily basis. Some don't expire until 2019. And Davis would have to win approval for each appointment from what is shaping up to be the most business-friendly state senate Texas has seen since Spindletop.

Recently, the Austin American Statesman reviewed over 8,000 Perry appointments, and found:

Nearly 4 in 5 Perry appointees are white, even as the portion of whites in the state dropped from 55 percent in 2000 shortly before Bush left office to 44 percent in 2010. Overall, 77 percent of his appointees have been white, and 67 percent are male.

Perry has appointed 90 of his former employees to boards and commissions, placing trusted lieutenants in the upper echelons of government agencies. Twenty-three of those one-time governor’s office workers were given paid appointments.

Nearly a quarter of appointees are donors to Perry’s campaigns, together giving more than $20 million. That constitutes a fifth of all contributions he has received during his time as governor.

No agency reflects Perry's these trends more thoroughly than the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

Zac Covar, white and male, was a Perry aide, who then became an assistant to the TCEQ Chairman appointed by Perry, who then became Executive Director of the TCEQ, who then became one of three Commissioners himself. He's also a fellow Aggie, graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Poultry Science from Texas A&M University, making him imminently qualified to help run the largest environmental agency in the free world outside of the EPA. His term expires next year.

Commissioner Toby Baker, white and male, was another Perry aide, and another fellow Aggie, with a degree in Public Administration. His term expires in 2017.

Chairman Bryan Shaw, white and male, is still another fellow poultry science degreed graduate of A&M, although you be hard-pressed to discover that in his official job description now days (two chicken scientists ruling the TCEQ coop seems to be an embarasment that even shames the Perryites). Since he was last appointed in 2013, his six-year term won't be up until 2019.

It's not only the top administrators at TCEQ who are full-fledged mini-mes of Perry. It's also the agency's Chief Engineer Susana M. Hildebrand, who's been known to flat out lie to Legislative Committees about the inconvenient results of studies that don't reflect the hardcore pro-leave-industry-alone views of the Perry Administration. It's the TCEQ's Chief Toxicologist, Michael Honeycutt, who keeps insisting that smog really isn't that bad for you. And on and on.

The result of all this political in-breeding is an agency which is the largest purveyor of junk science in the state, taking every industry-financed "study" and promoting it as if it were gospel, even if it's in the extreme minority of scientific opinion, while discounting the overwhelming collection of independent academic reviews that contradicts it. That's how you arrive at the point where the state's major environmental agency says there's no such thing as climate change, no harm in smog, and the continuing release of millions of tons toxins are no big deal. That's how a month before Holcim decides to install SCR at its Midlothian cement plant, a representative of TCEQ can say straight faced in an Arlington regional air quality meeting that the technology "isn't technically feasible."

This is why many of the state's citizen groups have given up on anything useful coming out of Austin for the foreseeable future. They've decided that If change is going to happen in Texas it'll be at the local level, where Rick Perry's fingerprints have not yet smudged all reconciliation with reality. And that's exactly why recent local expressions of people power, like the Dallas drilling ordinance and the Denton fracking ban vote are such a threat to an otherwise watertight hegemony emanating from the Governor's office.

TCEQ: Link Between Fracking and Air Quality, No Cement Controls Just “Because”: Highlights From Tuesday’s Air Meeting

Dallas Resident Liz Alexander showed up at the Council of Governments meeting room on Tuesday to lend her support to the effort to get more out of an anemic state ant-smog plan than the state wants to give. She was a warm body whose presence would be its own statement of concern. She was being a good trooper by just showing up.

Dallas Resident Liz Alexander showed up at the Council of Governments meeting room on Tuesday to lend her support to the effort to get more out of an anemic state ant-smog plan than the state wants to give. She was a warm body whose presence would be its own statement of concern. She was being a good trooper by just showing up.

At first she sat far from the action amidst the rows of seats for bystanders and, despite encouragement, was resigned to just listening, because as she explained, "she didn't know enough to ask questions."

Then someone urged her to move up to the rectangle of tables where the presenters stand and deliver, where there are microphones to raise the volume of concerns and questions that might be posed by mind-numbing reassurances that everything is going hunky-dory. As more of these air quality meetings have occurred, citizens have been less and less shy about taking up these front row seats that look more official than the rest; look like they should be reserved for guys in suits. Increasingly they're occupied by people in street clothes.

And then, after much information had been paraded in front of Liz, she did something she did not think she was qualified to do only about 90 minutes earlier. She asked a question. It was about what assumptions had been included in the information about unspent air pollution clean-up dollars that are piling up in Austin. She got an answer from a local COG staff person in real time that satisfied her. In the space of one meeting she moved from spectator to participant.

And she wasn't the only one. More than any other meeting so far, this one involved more citizens asking more questions about more subjects – and it revealed just how thin the state's rationale is for doing nothing.

As predicted, it was a day for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to explain why its new DFW anti-smog plan was really going to work this time – unlike the five previous failures – and why it wasn't going to be considering any new controls on the Midlothian cement plants or on gas compressors – a refutation of the case Downwinders at Risk had made in its June 16th presentation.

But here's what really happened: For the first time in these proceedings the state admitted that oil and gas emissions have a big influence on regional air quality. And when a former County Judge asked an TCEQ's Air Quality Manager specifically why anti-smog controls already being used on cement kilns in Europe were not being considered for the Midlothian kilns, the staffer couldn't say, offering up only the longest, most pregnant pause by any state staffer in the history of these meetings.

After being heavily criticized for months for leaving at least four monitors above the 75 ppb federal smog standard even after its plan had ended in 2018, the state came back to this meeting saying they only had three sites above 75 ppb now, and by margins that didn't exceed the standard by more than 1 part per billion. Between June and August, there had been a remarkable drop in future estimated smog levels at the area's monitoring sties in the state's computer modeling – particularly at the historically most stubborn monitoring sites in Denton and Northwest Tarrant County.

What had caused this drop? A relatively modest decrease in Nitrogen Oxide pollution of around seven tons a day and a decrease in Volatile Organic Compounds of about 15 tons per day. That's not a lot of pollution to produce such a large decrease in monitor readings in the computer model.

A more important question is: where did the decreases in air pollution come from that could produce such dramatic results in the modeling? The answer: primarily from oil and gas industry sources. Based on TCEQ's own formula relying on the declining number of new wells being drilled in the Barnett Shale.

For the moment forget the methodological qualms you might have about that declining well assumption. Instead, appreciate the fact that the same state agency that couldn't bring itself to ever say the Barnett Shale was producing air pollution holding DFW back from meeting Clean Air Act smog standards now says that it's decreases in that very kind of pollution that are having such a substantial effect on the monitors in the western part of the Metromess that have been the most resistant to other control strategies. TCEQ has just proven a causal link its been denying for over seven years now.

It can't be just a one-way street. If declining oil and gas air pollution equals better air quality in the TCEQ's computer model, so increases in oil and gas pollution must lead to worse air quality.

There are all kinds of reasons to doubt that the drop in total oil and gas air pollution will happen at all or drop as fast or as sharply as the TCEQ predicts. Afterall, they're 0 for 5 in such matters. They may be underestimating the amount of total air pollution from all gas and oil sources and so the drop will not be as sharp. They may be underestimating the impact of lots of new lift compressors that will be showing up to squeeze the last bits of gas from older wells even as new wells are not drilled as often. But as of Tuesday the link has been made by TCEQ itself that such a drop results in big decreases in smog levels in Denton and Northwest Tarrant County. That's something that citizens can use to argue as proof of the impact of oil and gas facilities on local air quality.

Of course, it only took the span of about 30 minutes for the TCEQ to internally contradict itself about those results.

According to TCEQ computer modelers, natural gas Compressor Stations large enough to be considered "point sources" just like cement kilns or power plants will be responsible for over 17 tons of Nitrogen Oxides, and 26 tons of VOCs a day in 2018 – well over the amount of oil and gas pollution decreases that resulted in those lower monitoring numbers in Denton and NW Tarrant County. But according to the TCEQ staff responsible for suggesting new controls in the new smog plan, those numbers are not large enough to have an impact on improving DFW air quality or warranting a policy of electrification for those compressors that could reduce their air pollution to a fraction of those volumes.

So while 7 tons of NOx reduction from Oil and Gas sources is large enough to bring some of the most stubborn monitors down a whole part per billion, reducing air pollution from Oil and Gas sources by another 17 tons of NOx reduction would have no effect on DFW air quality at all and it's just not worth it to make them electrify compressors. Honest, that was the logic in play on Monday, and it didn't hold up very well under questions from people like Liz Alexander.

And that was all before you got to why the Midlothian cement kilns could not, no way, no how, possibly, under any circumstance, be required to install Selective Catalytic Reduction controls, just like their European counterparts have done over the last 15 years.

Turns out, it's just because.

Oh, the TCEQ staffer cited four criteria for any new control measure to meet before it could be considered. Let's see, there was "technological feasibility." Since there are at least seven full-scale SCR units up and running in Europe, that couldn't be a problem. It's accepted technology by some of the same companies operating kilns in the US – including LaFarge-Holcim.

There was "economic feasibility." And since there are all those SCR examples already in the European market and no company has gone bankrupt running them, that's also off the table. Plus the fact that the TCEQ's own 2005 study of SCR concluded it was "available technology" then that would only cost $1000 to $3,000 per ton of NOx removed – versus the up to $15,000 per ton of NOx removed ratio allowed in the state's own official diesel engine replacement program. Coming in at one-fifth the cost of what the state already said was economically feasible, it certainly ruled out that one.

There was the third criterion – that controls couldn't cause ‘‘substantial widespread and long-term adverse impacts.’’ The state said that wasn't the reason they couldn't be considered either, although the TCEQ staffers seemed to hedge a bit here, seemingly wanting to say that, really, they didn't want to cause themselves adverse impact by admitting that they had been wrong for over a decade about this stuff.

The proposed control cannot be ‘‘absurd, unenforceable, or impracticable.’’ Clearly, if the Europeans are doing it on their kilns, it's none of those either. It's quantifiable, and up and running in power plants, cement kilns and incinerators.

And it has to speed the attainment deadline by a year. No problem. SCR could do that if it was installed in a timely fashion.

So at the end of the state's presentation, former Dallas County Judge Margaret Keliher asked the TCEQ staffer exactly why SCR wasn't considered a possible pollution control measure since none of these criteria that had been presented seem to rule it out. And the TCEQ's staffer's response was…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

No, really, that was the response. She couldn't say. It was that embarrassing. Because the rejection of SCR by TCEQ isn't based on any of those criteria. It's based on a political decision that's been made that no new pollution controls will be sought on the kilns or any other major industrial polluter as long as Rick Perry is running for President. Or "just because."

How ridiculous is this? At this point the TCEQ is taking an even more regressive view of SCR controls than the cement industry itself. In June, Holcim Cement's Midlothian plant requested a permit from the state that would allow it to build either a Thermal Oxidizer or an SCR until for the control of VOC pollution. Being the free market fanatics the Perry Administration claims to be, doesn't the fact that one of the Midlothian cement plants is asking for a permit that includes the possibility of installing SCR mean it's automatically technologically and economically feasible? The market is never wrong, right? Are the folks at Holcim so enamored of kinky, off-the-wall green technology that they'll just include it in a permit for laughs? These guys are Swiss engineers. They have no sense of humor.

Denial of SCR as a viable control measure that could reduce smog pollution is making the TCEQ contort into sillier and sillier positions. It's making them deny the conclusions of their own almost-decade old report that said it was available to put in a kiln in 2005. It's making them deny the fact that SCR is up and running at over half a dozen kilns in Europe. It's forcing them to once again use the "Midlothian limestone is magically special" defense that has been used to forestall any progress in pollution control there over the last 25 years. The arguments used against SCR are exactly the same as were used against the adoption of less effective SNCR technology before it was mandated. In case you hadn't noticed, they're still making cement in Midlothian despite the burden of having to nominally control their air pollution.

The state wants to power through this anti-smog plan just like they did the last one in 2011. They don't want to have to make industry do anything. But at this point the denial of SCR as a control measure to be included in the next DFW anti-smog plan is so absurd, as is the justification for electrification of gas compressors, that it might be fodder in the next citizens lawsuit over a DFW anti-smog plan, which usually follows these things like mushrooms after a rainstorm.

Want to get involved in this fight and make it more difficult for the state to get away with doing nothing at all about DFW smog – again? Please consider attending our next DFW Clean Air Network meeting – THIS SUNDAY, AUGUST 17th, from 3:30 pm to 5:30 pm at the offices of the Texas Campaign for the Environment across from Lee Park in Dallas, 3303 Lee Pkwy, Suite #402 (214) 599-7840. Citizens are the only force that can make this plan better. Be there, or breathe bad air.

Want to Quiz the State Over Crappy DFW Air? Tomorrow’s Your Chance As the Empire Strikes Back

Rick Perry's minions at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) are drafting a new anti-smog plan for DFW this summer and fall. The only access DFW residents have to how it's being done and why are through periodical regional air quality meetings hosted by the Council of Governments in Arlington. At these meetings staff from TCEQ make presentations on why the air in DFW is getting so much better and why no new pollution control measures are needed to reach smog standards required by the Clean Air Act – despite the fact that the state is 0 for 5 in plans to attain compliance with those standards. In fact, the last such plan from Austin actually resulted in slightly higher levels of smog.

Rick Perry's minions at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) are drafting a new anti-smog plan for DFW this summer and fall. The only access DFW residents have to how it's being done and why are through periodical regional air quality meetings hosted by the Council of Governments in Arlington. At these meetings staff from TCEQ make presentations on why the air in DFW is getting so much better and why no new pollution control measures are needed to reach smog standards required by the Clean Air Act – despite the fact that the state is 0 for 5 in plans to attain compliance with those standards. In fact, the last such plan from Austin actually resulted in slightly higher levels of smog.

Tomorrow, Tuesday August 12th there will be another such regional air quality meeting. It's going on from 10 am to 12 noon at the Council of Government headquarters in Arlington at 616 Six Flags Road, right across from the amusement park (insert your own joke here). Of course, it's during business hours – you didn't think they're going to make it easy for the public to attend, did you?

Despite that, beginning in April more and more local residents have been showing up at these meetings to express their concern at the lack of progress in bringing safe and legal air to DFW. One of the reasons is that these meetings are the only forum available to citizens to question TCEQ staff in person – and then ask follow-up questions if you don't like the first answer. It's their only opportunity to be a kind of clean air Perry Mason and because it's a public meeting and everyone's looking at them, TCEQ staff have to at least make an attempt to answer those questions.

Things reached a high point at the last meeting in June when Downwinders and the Sierra Club were allowed to make their own presentations about why the state is falling down on its job. A roomful of concerned citizens and elected officials saw the case against the state was self-evident – all we had to do was quote from its own past press releases and memos to make our point.

Tomorrow's meeting is the first chance the state will have to give a rebuttal to those citizen group presentations. Staff will present all the reasons why we don't need new air pollution controls on the Midlothian cement plants, the gas industry, or the East Texas coal plants, and why another do-nothing anti-smog plan from Austin will be just dandy.

And so, if between inhaler bursts you ever wanted to quiz officials about Rick Perry's air pollution strategies, tomorrow's meeting is going to be your chance.

You may think you're not qualified, but you'd be wrong. Simple common sense questions are often the hardest ones for the TCEQ staff to answer, because you know, they're based on common sense, and so many of their policies aren't.

This is how citizens uncovered the fact that TCEQ was hiding oil and gas pollution in other categories not named oil and gas. This is how we got the TCEQ to release maps of where all the gas industry compressors in DFW are after first explaining there were no such maps. And so on.

All that you need is a curious mind. They're not prepared for those.

Tomorrow, 10 to 12 noon is your opportunity to show your concern about breathing bad air, your desire to see major industrial sources of pollution better controlled, and why you want these anti-smog plans to do more. Be there or keep breathing bad air.

EPA Scientists Say Current Smog Standard Not Protective Of Public Heath Even While TCEQ Blows Off Current One

It's been a pretty nice summer in DFW so far hasn't it? Wetter and cooler than usual. More wind. According to the stats, this past month was the first June without any 100 degree days in seven years or so. Consequently, it's also the first June in forever that hasn't seen any "Orange" or "Red" ozone alert days. If this keeps up, DFW may actually come into compliance with the 1997 ozone standard of 85 parts per billion (ppb) over an 8-hour time period – a first as well.

It's been a pretty nice summer in DFW so far hasn't it? Wetter and cooler than usual. More wind. According to the stats, this past month was the first June without any 100 degree days in seven years or so. Consequently, it's also the first June in forever that hasn't seen any "Orange" or "Red" ozone alert days. If this keeps up, DFW may actually come into compliance with the 1997 ozone standard of 85 parts per billion (ppb) over an 8-hour time period – a first as well.

But unless you think "global weirding" is going to produce these kinds of summers routinely from here on out, there's little cause for comfort. This year's cleaner air is a direct result of cooler weather. Substitute the hellish summer of 2011 for this mild one and you'd be seeing ozone alerts filling up your e-mail box. As a result, it's not out of the question we could meet the standard this year, but flunk it in 2015 if the weather reverts back to "normal."

In addition, while we may come in under the 1987 smog standard for the first time, the public health goal posts have moved with better science. In 2008, the Bush Administration lowered the acceptable level of smog to 75 ppb. That's the goal of the clean air plan that Downwinders and other groups are fighting the state over right now, saying it's not adequate to even get to that 75 ppb level.

Texas Commission on Environmental Quality staff say we don't need to implement any major pollution control measures on cement kilns, power plants, or natural gas facilities to reach this 75 ppb goal by the deadline in 2018. All we have to do is sit back and let a new federal gasoline standard hit the market in 2017 and we'll all be fine – well, except for those millions of residents who'll be breathing-in smog greater than 75 ppb on the north and western side of the Metromess. But the TCEQ staff say we'll be "close enough." No harm, no foul say the folks from the agency where smog is not considered bad for you.

But close enough should only count in horseshoes and hand grenades, not what people breathe into their lungs. And while some of us are trying to make sure the new TCEQ plan is serious about reaching an air quality goal that's now six years old, the level of ozone considered "safe" by experts is once again going down.

In a letter to EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy last week, the Agency's own Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC) recommended a new smog standard of between 60 and 70 ppb, saying that there's a boatload of evidence showing that the 75 ppb level is not protective of human health, and even at 70 ppb there's significant public health harm done by bad air.

"At 70 ppb, there is substantial scientific evidence of adverse effects….including decrease in lung function, increase in respiratory symptoms, and increase in airway inflammation. Although a level of 70 ppb is more protective of public health than the current standard, it may not meet the statutory requirement to protect public health with an adequate margin of safety….our policy advice is to set the level of the standard lower than 70 ppb within a range down to 60 ppb…"

This recommendation was not unexpected. Every five years, the CASAC is legally obligated to review the scientific literature to make sure the federal ozone standard is giving adequate protection to public health. The last time it did so in 2008, the panel came to a similar conclusion to lower it somewhere between 65 and 70 ppb, but the Bush Administration ignored its own scientists and chose the higher standard instead. An Obama EPA was supposed to correct that mistake when it came into office, but then-EPA head Lisa Jackson got mugged on her way to the White House by the President's re-election campaign. Any changes were put on hold until that five year review clock began ticking again. And now the official alarm has gone off on that clock. The result is a re-affirmation of the earlier findings, this time with even more science to back up the changes.

As a result, EPA will have to decide whether or not to adopt the tougher recommendations of its scientists by December 1st of this year. If they do, a new standard will be officially adopted by 2015 and we'll have to write a new clean air plan in a couple of years to achieve that goal by the end of the decade. If it doesn't, they'll be sued, with the CASAC letter as exhibit #1, and they'll lose and have to set a new standard anyway.

Why is that important to the current debate over TCEQ's plan to meet the 75 standard? Because the TCEQ plan leaves at least four monitors, spread out from Denton, to Keller, to Eagle Mountain Lake above 75 ppb – a standard that EPA scientists now say conclusively is not protecting public health.

"Close enough" to that 75 ppb level turns out to be too far away from real protection in light of the new recommendations for a standard below 70 ppb from the Science Advisory Committee. And that assumes you believe the computer modeling TCEQ has done to support its plan. To date, the state is 0 for 5 going back to 1991 in being able to accurately predict these things. If history is any indication, the state's plan will fail to reach its goal of 75 ppb at just about every one of the 20 monitors in DFW, not just four.

If you know your target of 75 ppb of smog over an 8-hour period is no longer a safe standard, and your current plan condones levels above that, it's not really a clean air plan.

December is not only when EPA must decide if it's going to pursue a lower smog standard. It's also when the state is scheduled to take public comment on its current DFW anti-smog plan. So you have the surreal possibility of holding public hearings over the merits of an already obsolete plan that isn't even serious about reaching its obsolete goal.

This is why DFW residents must demand a plan from Austin that aims lower, not higher. It's why they must demand the EPA not allow TCEQ to get away with being "close enough" to a standard that's not protecting their health. A real clean air plan would be shooting for an average of 65-70 ppb knowing that that standard will be coming down the road sooner or later. A real clean air plan wouldn't allow any monitor to exceed the current 75 standard. A real clean air plan would try to do its best to protect public health by implementing pollution control measures on the sources of smog that are the cheapest and most effective to target – Midlothian's cement plants, east and central Texas coal plants, and the natural gas industry.

And that's exactly what Downwinders and other members of the new DFW Clean Air Network are trying to do. We're pushing for stricter EPA enforcement of the 75 ppb standard, and we're pushing for adoption of "Reasonably Available Control Measures" on the cement plants and gas compressors – now, not later. Because the only way DFW breathers are going to get a better clean air plan out of Austin and Washington is by organizing for one themselves.

Study: Climate Change Will Likely Increase DFW Smog

Just last week at the June regional air quality planning meeting the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality was bemoaning the fact that the weather too often determines how bad an "ozone season" DFW will have. And it's true. When we have really hot, dry, and windless summers, ozone levels soar as they did as recently as 2011-2012 when the recent drought seemed to reach its most awful heights in DFW. Conversely, when we have relatively cool, wet and windy summers, ozone levels abate, as they seem to be doing this year – at least so far.

Just last week at the June regional air quality planning meeting the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality was bemoaning the fact that the weather too often determines how bad an "ozone season" DFW will have. And it's true. When we have really hot, dry, and windless summers, ozone levels soar as they did as recently as 2011-2012 when the recent drought seemed to reach its most awful heights in DFW. Conversely, when we have relatively cool, wet and windy summers, ozone levels abate, as they seem to be doing this year – at least so far.

Of course, the TCEQ spokesperson was using weather as an excuse why DFW hadn't yet achieved compliance with the 1997 ozone standard after two tries that fell short. Completely overlooked was the fact that the last state air plan for DFW in 2011 promised historically low ozone levels by 2013 without any new pollution controls on major sources of pollution. Combine that lack of action with a really hot, dry summer like we saw in 2011, and you get the first clean air plan ever to leave ozone levels higher after it ended than when it started.

That's why it's important to think about the weather when you're trying to build new clean air plans for DFW that stretch years into the future. Air quality planners have to ask themselves if between now and the next federal clean air plan deadline of 2018, will there be more summers like this seemingly anomalous one, or will they more like the summer of 2011 when we had a constant barrage of 100 degree plus days as early as March?

Currently, the TCEQ is using a stretch of bad air days from 2006 to predict ozone levels between now and 2018 in their computer model for the DFW air plan to comply with the new, tougher 2008 ozone standard. But 2006 was pre-drought. Although they say they're "adjusting" the meteorology to compensate for weather changes since then, do you really trust TCEQ to assume worst-case weather scenarios when they're still trying to hide the smog impacts of gas pollution from the public? Us either.

So it's with more than a little self-interest that we note a new Stanford study with the too-sexy title of "Occurrence and Persistence of Future Atmospheric Stagnation Events" concluding that the Western US, including Texas, should expect hotter and therefore smoggier summers thanks to climate change. Why? Because hotter temperatures will slow the flow of air around the globe. That means less wind, and less wind means more time for smog-forming chemicals to sit and bake in the hot sun and form harmful levels of ozone. Historically, most of our worst ozone days are when winds are blowing less than 5 mph – stagnate air.

DFW isn't like Denver or LA where mountains form bowls around the urban areas and trap pollution in inversions. But the new study concludes the impact from global warming could have the same effect on the Texas prairie by stagnating air currents:

"Our analysis projects increases in stagnation occurrence that cover 55% of the current global population, with areas of increase affecting ten times more people than areas of decrease. By the late twenty-first century, robust increases of up to 40 days per year are projected throughout the majority of the tropics and subtropics, as well as within isolated mid-latitude regions. Potential impacts over India, Mexico and the western US are particularly acute owing to the intersection of large populations and increases in the persistence of stagnation events, including those of extreme duration. These results indicate that anthropogenic climate change is likely to alter the level of pollutant management required to meet future air quality targets."

And who's more prepared to deal with the "pollution management required to meet future (re: tougher) air quality targets than the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality? Almost any one, including your 13-year old niece who's done so well in 8th grade science this year. Because not only is it the TCEQ's official position that smog isn't all that bad for you, but that there's really no such thing as climate change. It's why you should bring a boatload of skepticism to the computer model that's driving the currently proposed DFW clean air plan. To plug hotter and hotter temps into the DFW smog model for coming years would be admitting to a phenomena that the Rick Perry administration in Austin just can't bring itself to concede. One more example of how the DFW plan is being driven by politics, not science.

As the TCEQ's own staff admitted last week, DFW's ozone levels are often hostage to the weather. If you're model isn't correctly estimating the weather during future ozone seasons, chances are your estimates of future ozone levels will be off as well. But of course, since smog isn't really bad for you there's no downside to being wrong about these things at TCEQ HQ, and only an upside in GOP primaries.

For the rest of us who believe what the science tells us, the consequences are more dire. As the VICE magazine take on the Stanford study said:

"….one reason this study is so important to the climate change conversation—it underlines the public health threat posed by climbing temps. When Obama was touting the EPA's new carbon regulations, he emphasized the public health benefits of drawing down emissions: It would reduce asthma and respiratory illness, he pointed out. But that's largely because shuttering dirty power plants cuts both carbon and particulate pollutants simultaneously; fighting climate change also means fighting asthma.

Now, scientists have demonstrated there's an additional layer of concern to grapple with on the pollution front; climate change is going to begin blocking cities' toxic release valves. If we don't work to slow carbon emissions, these steamier cities will find their streets clogged with stagnant smog. Scrubbing that pollution and finding novel ways to clear the air, too, then, will prove to be a pressing concern in the not-so-distant future.

Rick Perry, with a Smoking Gun, in the COG Headquarters: Monday at 10 am

The latest chapter in a decades old mystery game of "Get a Clue" happens tomorrow morning, Monday, June 16th when representatives of the Sierra Club and Downwinders at Risk present their case against the current state anti-smog plan during the regional air planning meeting at the headquarters of the North Texas Council of Governments, 616 Six Flags Road in Arlington. Come find out who and/or what keeps the DFW area from ever meeting federal clean air standards year after year and what can be done about it. The meeting starts at 10 am. Citizen groups are expected to do their presentations in the 11 to 12 hour. Then we'll all have a debriefing lunch at the Subway's down the street hosted by State Representative Lon Burnam. Y'all come.

The latest chapter in a decades old mystery game of "Get a Clue" happens tomorrow morning, Monday, June 16th when representatives of the Sierra Club and Downwinders at Risk present their case against the current state anti-smog plan during the regional air planning meeting at the headquarters of the North Texas Council of Governments, 616 Six Flags Road in Arlington. Come find out who and/or what keeps the DFW area from ever meeting federal clean air standards year after year and what can be done about it. The meeting starts at 10 am. Citizen groups are expected to do their presentations in the 11 to 12 hour. Then we'll all have a debriefing lunch at the Subway's down the street hosted by State Representative Lon Burnam. Y'all come.

A Barnett Shale Manifesto…From Austin

Sometimes it takes a perspective above the grind of trench warfare to give you a better sense of what the entire battlefield looks like. That's what UT Law Professor Rachel Rawlins has done for Barnett Shale activists with the recent publication of her article "Planning for Fracking on the Barnett Shale: Urban Air Pollution, Improving Health Based Regulation, and the Role of Local Governments" in the new Virginia Environmental Law Review.

Sometimes it takes a perspective above the grind of trench warfare to give you a better sense of what the entire battlefield looks like. That's what UT Law Professor Rachel Rawlins has done for Barnett Shale activists with the recent publication of her article "Planning for Fracking on the Barnett Shale: Urban Air Pollution, Improving Health Based Regulation, and the Role of Local Governments" in the new Virginia Environmental Law Review.

Don't let the academic title fool you. This is a call for a radically new approach to how communities in Texas regulate the risks of fracking, and every other type of heavy industry. We put the link up for the piece on our Facebook page on Saturday based on a quick reading of its commentary on the Flower Mound cancer cluster, but it's more, so much more than that. Among other things, it's a comprehensive rebuttal of every claim of safety and well-being ever issued by the industry or state authorities about the health of residents living in the Barnett Shale, of which the Flower Mound case is only one example. Rawlins has produced a one-stop catalog of each major air pollution health controversy in the Barnett since concerns began to grow in the last decade, with an almost 30-page review of why no industry or government-sponsored study of fracking pollution and its health effects is a satisfactory response to those concerns. Want to convince your local officials that fracking isn't as safe as it's touted? Here's the staggering blow-by-blow commentary to do it.

But all of that documentation is presented in service to making the point that current state and federal regulation of fracking is failing to protect public health, both in design and in practice. Professor Rawlins' solution to this problem is not to give the state and federal government more power to regulate the gas industry. No, it's to turn the current regulatory framework upside down and give more power to local governments to do the things that the state and federal government should be doing.

In making this recommendation, she echoes the strategy that's been driving Downwinders since it was founded – that the best way to regulate pollution problems is at the local level where the most harm is being done, and it should be directed by the people being harmed. This is what drove our Green Cement campaign that closed the last obsolete wet cement kiln in Texas. This is what fueled our campaign to close down the trailer park-come-lead smelter in Frisco. And it's what was behind the recent Dallas fights over drilling. In each case, it wasn't Austin or Washington DC that was the instrument of change – it was local governments, pressed by their constituents, flexing their regulatory powers. The same thing is driving activists in Denton who are organizing the ban fracking petition drive and vote.

This strategy avoids battles where industry is strongest – in the halls of the state capitol and in DC, where citizens are outspent millions to one. Instead, it takes the fight to neighborhoods where the harm is being done or proposed, where people have the most to lose, where the heat that can be applied to elected officials is more intense. Citizens will still get outspent, but the money doesn't seem to buy corporations as much influence among those actually breathing the fumes of the drilling site, or smokestack.

Particularly now, with corporate-friendly faux-Tea Party types in control of state government and the House of Representatives in DC, there is little room for grassroots campaigns to make a difference by passing new legislation. Even if by some miracle a few bills did pass, their enforcement would be up to the same state or federal agencies that are currently failing citizens. Local is more direct, and more accountable. Professor Rawlins agrees, and spends most of the rest of her 81-page journal article citing the ways in which local control of fracking in the Barnett Shale is hampered by the out-dated top-down approach to regulation, and what should be done to fix that.

Included in her recommendations are two long-term Downwinders projects: Allowing local governments to close the "off-sets" loophole for the gas industry that exempts them from having to compensate for their smog-forming pollution in already smoggy areas like DFW, and creating California-like local air pollution control districts that could set their own health based exposure standards and pollution control measures without having to go through Austin or DC.

If there's a single major fault in Rawlins's analysis, it's that she believes more local control of pollution risks is itself dependent on action by an unwilling state government. But Downwinders and others have shown that isn't true. Our most significant and far-reaching victories – from the closing of the Midlothian wet kilns to the new Dallas drilling ordinance – have all taken place while Rick Perry was Governor and the state legislature was in the hands of our opponents. We did these things despite Austin, not because we had its permission. Local zoning laws, local permitting rules, local nuisance acts, and other local powers are under-utilized by both residents and their elected officials when it comes to pollution hazards.

The same is true now of Downwinders' off-sets campaign aimed at the gas industry. We think we've found a way to avoid the "preemption" argument that would keep local governments from acting on smog pollution from gas sources by aiming the off-sets at Greenhouse gases – an area of regulation Texas is loathe to enter. By targeting GHG reduction, we also reduce a lot of toxic and smog-forming air pollution. It's a back door way, but it accomplishes the same goal. It's going to be up to Texas activists to sew similar small threads of change through an otherwise hostile political environment.

Even given that flaw, Professor Rawlins' introduction to her article is the most concise summary of the air pollution problems caused by gas mining and production in the Barnett, as well as the most credible call to action for a new way of doing business there. Here it is reprinted in full for your consideration:

In the last decade hydraulic fracturing for natural gas has exploded on the Barnett Shale in Texas. The region is now home to the most intensive hydraulic fracking and gas production activities ever undertaken in densely urbanized areas. Faced with minimal state and federal regulation, Texas cities are on the front line in the effort to figure out how best to balance industry, land use, and environmental concerns. Local governments in Texas, however, do not currently have the regulatory authority, capacity, or the information required to closet he regulatory gap. Using the community experience on the Barnett Shale as a case study, this article focuses on the legal and regulatory framework governing air emissions and proposes changes to the current regulatory structure.

Under both the state and federal programs, the regulation of hazardous air emissions from gas operations is based largely on questions of cost and available technology. There is no comprehensive cumulative risk assessment to consider the potential impact to public health in urban areas. Drilling operations are being conducted in residential areas. Residents living in close proximity to gas operations on the Barnett Shale have voiced serious concerns for their health, which have yet to be comprehensively evaluated. Given the complexityof the science, and the dearth of clear, transparent, and enforceable standards, inadequate studies and limited statistical analysis have been allowed to provide potentially false assurances. The politically expedient bottom line dominates with little attention paid to the quality of the science or the adequacy of the standards.

Determining and applying comprehensive health-based standards for hazardous air pollutants has been largely abandoned at the federal level given uncertainties in the science, difficulties of determining and

measuring “safe” levels of toxic pollutants, and the potential for economic disruption. Neither the state nor the federal government has set enforceable ambient standards for hazardous air pollutants.Identifying cumulative air pollution problems that may occur in urban areas, the State of California has called upon local governments to identify “hot spots” and to consider air quality issues in their planning and zoning actions. In Texas, however, preemption discussions dominate the analysis. Any local government regulation that might provide protection from toxic air emissions otherwise regulated by the State must be justified by some other public purpose.

Texas should consider authorizing and encouraging local level air quality planning for industrial activities, similar to what California has done. Care should be taken to separate these facilities from sensitive receptors and “hot spots” that may already be burdened with excessive hazardous air emissions. Given the difficulty of the task, there is also an important role for the state and federal governments in working to establish ambient standards for hazardous air pollutants, as well as standards for health based assessment and public communication. The uncertainty inherent in any of these standards should be made clear and accessible to local governments so that it may be considered in making appropriate and protective land use decisions. Texas should consider allowing local governments to have the power to establish ambient air quality standards, emissions limitations, monitoring, reporting, and offsets for hazardous air pollutants, following the model applied to conventional air pollutants pursuant to the federal program.

Professor Rawlins' article provides Barnett Shale activists with a new map to guide them toward more effective action. We'd all do well to study it and pick local battles that promise to contribute toward its realization.

New UNT Study-In-Progress Links Gas Pollution to Persistent DFW Smog

This is why it's important for citizens to have real scientific horsepower.

This is why it's important for citizens to have real scientific horsepower.

DFW has a smog problem. It's not as bad as it used to be, but it's still at unsafe and illegal levels. And for the last four or five years, the air quality progress that should have been made has been stymied. Despite almost all large sources of smog-producing pollution being reduced in volume, our running average for ozone is actually a part per billion higher than it was in 2009.

Many local activists believe this lack of progress is due to the huge volumes of smog-producing air pollution being generated by the thousands of individual natural gas sites throughout the DFW region itself, as well as upwind gas and oil plays. In 2012, a Houston-based think tank released a report showing how a single gas flare or compressor could significantly impact downwind smog levels for up to 5 mile or more. Industry and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality say no, gas sources are not significant contributors to DFW smog. In fact, during this current round of planning, the state has gone out of its way to downplay the impact of gas pollution, including rolling back previous emission inventories and inventing new ways to estimates emissions from large facilities like compressor stations.

Into this debate steps a UNT graduate student offering a simple and eloquent scientific analysis that uses the state's own data on smog to indict the gas industry for its chronic persistence in DFW – especially in the western part of he Metromess, where Barnett Shale production is concentrated.

On Monday night Denton Record-Chronicle reporter Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe gave a summary of a presentation on local air quality she'd sat through that day at UNT:

"Graduate student Mahdi Ahmadi, working with his advisor, Dr. Kuruvilla John, downloaded the ozone air monitoring data from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality back to 1997, a total of more than 6.5 million data points, he said, and has been studying it for the past four months.

Ahmadi wanted to explore a basic question underlying a graphic frequently distributed by the TCEQ that shows gas wells going up in DFW as ozone goes down, which suggests in a not-very-scientific-at-all way, that the increasing number of gas wells is having no effect on the ozone.

Ahmadi adjusted for meteorological conditions to determine how much ozone DFW people are making and where. Such adjustments have been explored by others to understand better the parts of ozone-making we can control, because we can’t control the weather. He used an advanced statistical method on the data, called the Kolmogorov-Zurbenko filter, to separate the effects of atmospheric parameters from human activities.

According to the results, the air monitoring sites surrounded by oil and gas production activities, generally on the west side of DFW, show worse long-term trends in ozone reduction than those located farther from wells on the east side of DFW.

His spatial analysis of the data showed that ozone distribution has been disproportionally changed and appears linked to production activities, perhaps an explanation why residents on the western side of DFW are seeing more locally produced ozone, particularly since 2008.

Ahmadi's results are not definitive, and the paper he's writing is still a work-in-progress. But he's asking the right questions, and challenging the right unproven assumptions. He's at least put forth an hypothesis and is trying to prove or disprove it. He's using science. TCEQ's approach is all faith-based.

Anything that takes the focus off vehicle pollution is anathema to Austin and many local officials who want to pretend that industrial sources of air pollution don't impact the DFW region enough to make a difference so they don't have to regulate them. If there's a guiding principle to TCEQ's approach to this new clean air plan, due in July 2015, it's to avoid any excuse for new regulations while Rick Perry is running for President. The agency isn't interested in doing any kind of science that might challenge that perspective – no matter how persuasive. After all, you're talking about a group that doesn't believe smog is bad for you. TCEQ doesn't want to know the truth. It can't handle the truth. It's got an ideology and it's stickin' to it.

So it's up to young lowly graduate students from state universities armed only with a healthy sense of scientific curiosity to step up and start suggesting that the Emperor's computer model has no clothes, and offering up alternative scenarios to explain why DFW air quality is stuck in neutral. It turns out, just doing straight-up classroom science is enough to threaten the fragile House of Computer Cards with which the state's air plan is being built.

Perhaps equally as ominous for the success fo any new clean air plan is Ahmadi's discovery that ozone levels in DFW have been during the winter time, or "off-ozone-season." There could be a new normal, higher background level of smog affecting public health almost year round.

Mahdi Ahmadi's study is just one of the many that need to be done to construct an honest clean air plan for DFW, but it shows you what a curious mind and some computing power can do. Citizens can't trust the state to do the basic science necessary as long as the current cast of characters is running the show in Austin. EPA won't step in and stop the farce as long as TCEQ can make things work out on paper. If the scientific method is going to get used to build a better DFW clean air plan, it's going to have to be citizens who apply it.

2013 DFW Smog Report: Failure….Again

(Dallas)— On the eve of constructing yet another DFW clean air plan, the 2013 Ozone Season ended on Thursday the same way the previous 16 have ended: with North Texas out of compliance with the 1997 federal clean air standard.

(Dallas)— On the eve of constructing yet another DFW clean air plan, the 2013 Ozone Season ended on Thursday the same way the previous 16 have ended: with North Texas out of compliance with the 1997 federal clean air standard.

Even a mild summer with lower temperatures and more rain couldn't save the numbers from exceeding an illegal three-year running average of 85 parts per billion at monitors in Keller and Grapevine.

According to Jim Schermbeck with the clean air group Downwinders at Risk, what makes this year’s violation particularly troublesome is that the 1997 standard has been replaced with a more protective one that's 10 ppb lower. “For the next DFW air plan to succeed, it will have to reduce smog to levels that no DFW monitors have ever recorded. I don’t know anyone outside of Austin who thinks the state is up to that task.”

That new plan has its official kick-off event next Tuesday, November 5th, beginning at 9am in Arlington at the Council of Governments Headquarters. It's the first briefing from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality on the computer model it will be using to base the plan on. Everything about one of these plans is based on such a computer model, a model only the state can run. The plan must be submitted to EPA by June of 2015.

Even though extremely high ozone numbers were rarer this year, there were enough bad air days to cause the running averages of 10 out of 17 monitors, called "design values" to rise – not the kind of trend you want when you're next task is complying with a tougher standard.

Schermbeck was particularly concerned about a monitor near Mockingbird and I-35 in Central Dallas that’s seen its ozone average rise dramatically for three years in a row. “This is a monitor that had a "design value" of 67 parts per billion in 2010 – that is, it was in compliance with the new 75 ppb standard just three years ago. But now it’s up to 84 ppb and almost out of compliance with the 1997 standard. That's quite an increase in three years, and in a place where smog hasn’t been a problem for awhile.”

Every monitor inside the DFW metro area and even most "rural" monitors had a design value above the new standard of 75 ppb. Only Kaufman and Greenville made it under the wire, barely, with readings of 74 ppb.

As usual, the worst ozone levels were found in the northwest quadrant of the DFW area. This is a well-known historical pattern caused by the predominant southeast to northwest winds that blow pollution from the coast up through the coal and gas patches of East and Central Texas, over the Midlothian Industrial Complex and North Texas central urban cores into Northwest Tarrant Wise and Denton counties

This pattern has been the target of the last three state clean air plans, but has never been overcome. Schermbeck noted that last clean air plan to make a dent was the 2006 effort that produced lower numbers in steady fashion. Since 2008 however, air quality that was supposed to be getting better has gotten worse, or stagnated.

While cars have gotten cleaner during this time, and pollution from cement and coal plants has been reduced, there's one "source category" of pollution that's increased significantly since 2008: the gas industry.

In submitting the last DFW air plan to EPA in 2011, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality estimated there were more tons of smog-forming Volatile Organic Compounds being released by the gas industry in the official DFW "non-attainment area" than by all the cars and trucks on the road combined. That wasn't true in 2008.

Moreover, this is new air pollution in a smog non-attainment area that doesn't have to be off-set by reductions in pollution elsewhere in DFW. Unlike every other large industry, the gas industry is exempt from this offset requirement of the Clean Air Act.

Denton's Airport monitor's 4th highest reading of 85 ppb this summer, the one that officially counts toward its running average, was the highest such reading in the entire state, including Houston.

There's no doubt Denton is in the middle of the local gas patch, as are the Keller and Grapevine monitors that had the highest design values this year. Given the decreases in pollution from other categories, are gas patch emissions keeping these numbers from coming down they way they were supposed to? Austin keeps saying no, but the evidence is compelling.

Just last year there was a study out of Houston showing how a single flare or compressor station could significantly impact local ozone levels by as much as 5 or 10 ppbs. TCEQ itself just produced a study this last summer showing how Eagle Ford Shale gas pollution is increasing ozone levels in San Antonio.

Local Barnett Shale gas pollution might explain these Tarrant and Denton county monitors' problems, but they don't explain the rise in numbers of the Dallas monitors, since the wind during ozone season comes in from the south to southeast.

What new pollution is coming from that direction? Gas industry pollution from numerous compressor stations and processing plants stations in Freestone, Anderson, Limestone and other counties just about 90 to 100 miles south-southeast of Dallas. If one adds up all the emissions these facilities are allowed under their "standard permits." it exceeds the pollution from coal plants like Big Brown. That's a huge hit from sources that weren't there 10 years ago.

In effect, DFW is getting squeezed between gas pollution being produced in the middle of its urban areas, and gas pollution blowing in from the south.

“Officials with Rick Perry's TCEQ would rather drink lye than admit gas pollution is causing smog problems for DFW” says Schermbeck, “but such an admission might be the only way to bring DFW into compliance with the Clean Air Act.”

“This is why local DFW municipal and county governments serious about air quality must divorce themselves from Austin's politicized science and begin to seek their own solutions. Austin really isn't interested in solving DFWs chronic smog problems. Heck, the Commissioners who run TCEQ don't even believe smog IS a health problem.”