Fracking

“You got your fracking fluid in my cement!” Kiln Disposal of Drilling Wastes.

It was inevitable. Like chocolate and peanut butter. Like rats and the plague.

It was inevitable. Like chocolate and peanut butter. Like rats and the plague.

Two notoriously polluting industries find solace in each other's ability to scratch each other's dirty, irritating itches.

Cement plants are always looking for ways to get paid to burn other people's garbage. It takes a lot of energy to fire a 20-foot flame at 2000 degrees 24/7 in order to cook rock. It also takes a lot of "additives". That's why cement plants started burning other companies' hazardous wastes in the 70's and 80's. Because of a loophole in federal law, 50-year old cement plants with no modern pollution controls were allowed to charge for burning highly toxic wastes from refineries and chemical plants that were otherwise supposed to be going to fully-regulated hazardous waste disposal sites.

But those official sites cost more to use, and the cement plants cost so little. That's right, cement plants charged these polluters to dispose of their wastes, but not more than the incinerators or landfills with all the bells and whistles of "regulation." In this way, cement plant operators double dip – they don't have to shell out as much for fuel they'd have to buy, and they get paid a profit to be a Dispos-All for industry. And by the way, industry calls this "recycling."

Because of the persistence of Downwinders at Risk and other citizens' groups, this loophole has been slowly but surely closing, meaning less and less hazardous waste is being burned in US cement kilns. From a peak of almost 30 kilns burning toxics in the in the 1990's, we're now down to less than a dozen. But to take the place of this lucrative lost market, cement plants across the country are turning to "non-hazardous" waste to burn. Tires, but also municipal garbage, plastic wastes, used oils, shingles, car parts and other kinds of wastes. TXI's new permit allows the burning of a dozen different kinds of industrial wastes at its huge kiln in Midlothian.

While these wastes are classified as "non-hazardous," when they come in the front gate of a kiln, it turns out they can release a lot of toxic pollution when they're incinerated. Metals like lead and cadmium and arsenic that don't burn (consult your High School physics textbook) are present. So are PCB's that have Dioxin. But burning plastic or chlorinated wastes means you can generate Dioxins even without having them present in the wastes to begin with. There's also Mercury in some of the wastes from cars that TXI and other kilns wants to burn.

So you have the release of exactly the same kinds toxic pollution you were concerned about with the burning of officially-classified hazardous wastes. But now, it's taking place "legally," – or at least it is until the law hasn't catches-up with the consequences of this kind of low-rent disposal operation. Have a waste you want to get rid of? Send it to your local neighborhood cement plant. They'll burn anything.

Enter the Natural Gas industry. They've been getting a lot of bad PR lately about their own waste problems. They have billions of gallons of what they like to call "fracking fluid," and what the rest of us would call "hazardous wastes" that's so toxic it must be disposed of in a deep underground injection well after only being used once, isolated from the rest of the earth's environment forever. But because of some well-placed loopholes, this "fracking fluid" is not considered "official" hazardous waste under federal rules. It will just unofficially injure you with its toxins.

As it turns out, injecting billions of gallons of "non-hazardous" toxic liquid under extremely high pressure near deep underground faults is a sure way to generate earthquakes. And that's what's been happening. Not only in North Texas, but other places where there are lots of injection wells. There was another small one last night in Midlothian, right down the highway from a large deep injection well near Venus. Along with the fact that most fracking fluid cannot be or is not "recycled" now and can only be used once before disposal, the fracking fluid generated by the gas industry has turned into an embarrassing sore point.

If only there was some other way the gas industry could dispose of their drilling wastes. If only they could appear to be more environmentally-friendly and save money at the same time……

And there you have the genesis of a happy marriage made in polluter heaven. I have a facility that needs stuff to burn and mix, and I'm not that particular about what the stuff has in it. You have lots of stuff that needs to be burned, er, "recycled" and you spend less when you send it to a facility like mine not specifically built to do that job. Everybody wins!

"The use of drilling wastes and muds is most preferable in cement kilns, as a cement kiln can be an attractive, less expensive alternative to a rotary kiln. In cement kilns, drilling wastes with oily components can be used in a fuel-blending program to substitute for fuel that would otherwise be needed to fire the kiln.

Cement kiln temperatures (1,400 to 1,500 degrees C) and residence times are sufficient to achieve thermal destruction of organics. Cement kilns may also have pollution control devices to minimize emissions. The ash resulting from waste combustion becomes incorporated into the cement matrix, providing aluminum, silica, clay, and other minerals typically added in the cement raw material feed stream.

Recent studies have shown that it is feasible to use such drilling waste as substitute fuel in a cement plant. The drilling mud can be processed by a centrifuge to separate remaining water, compressed by a screw into a solid pump and conveyed.

The cement companies can contribute to sustainability also by improving their own internal practices such as improving energy efficiency and implementing recycling programs. Businesses can show commitments to sustainability through voluntary adopting the concepts of social and environmental responsibilities, implementing cleaner production practices, and accepting extended responsibilities for their products."

For veterans of The Cement Wars of the 1990's this rhetoric is certainly recycled. Cement Plants are Long, Hot and Good for America! Cement plants are the best disposal devices ever. They just make everything go "poof." That's why they were built specifically to dispose of wastes of all kinds – oh wait. nope. They were built to make cement. But how great is it that they can make an entire sideline business out of dealing with, and spewing toxic chemicals into the environment?

Even though the specific article deals with the Middle East, is there any question that a cement plant in Texas or Pennsylvania, or Ohio won't try to make the case for accepting drilling wastes, if they haven't already? The permit modification TXI received to burn plastics and car wastes from the State of Texas required no public notice at all. Citizens only found out after the fact. There are only about a dozen players left in the international cement market. If they're discussing this in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, chances are they're talking about it in Zurich, Heidelberg, and Midlothian too.

Developments like this are why its important to tell the EPA it's making a big mistake to delay and change its cement plant toxic emission rules. The industry's "inputs" are changing rapidly. Two years is too long. We need the protection of those new rules now. If you haven't already clicked and sent EPA an e-mail saying you oppose this delay, the "official" comment period is over, but it couldn't hurt for the folks in DC to see your "unofficial" opposition.

It's also a lesson in why "everything is connected." Don't live near a gas well? If you live in DFW, chances are you live downwind of a kiln that could be burning the wastes of gas wells.

Yes Virginia, There is a Pro-Cancer Lobby

The New York Times' Nicolas Kristof, who's established himself as one the nation's leading editorialist on the harms of what he calls "Big Chem," has another excellent piece in the Sunday edition.

The New York Times' Nicolas Kristof, who's established himself as one the nation's leading editorialist on the harms of what he calls "Big Chem," has another excellent piece in the Sunday edition.

Using the curious case of Formaldehyde, the carcinogen that isn't one according to the people who make money manufacturing it, Kristoff draws a portrait of the kind of industry-fueled professional obfuscation that Big Tobacco, Big Oil and Every other Big Industry of the last 60 years has used to escape necessary regulation.

Part of this strategy is to block, delay and bury information that proves your product's guilt, and so it is with Formaldehyde, something most of us think we only run across in High School biology labs. As it turns out, the chemicals is used in a wide variety of products and our homes are full of it. Our general exposure to formaldehyde has increased. This use and exposure has risen even as the World Health Organization and American scientists have concluded that formaldehyde causes cancer.

And so a seemingly innocuous document like the 500-page "Report on Carcinogens" from the National Institutes of Health becomes a real threat to the manufactured "uncertainty" the chemical industry has spent so much to construct.

“Formaldehyde is known to be a human carcinogen,” declared the most recent Report on Carcinogens, published in 2011. Previous editions had listed it only as a suspected carcinogen, but the newer report, citing many studies of human and animal exposure to formaldehyde, made the case that it was time to stop equivocating."

This conclusion made the report an instant target. Industry got its supporters in the house to demand a follow-up study for Formaldehyde and that no other Reports on Carcinogens be published with the new consensus language on its cancer-causing impacts.

So a chemical that the science says is clearly a carcinogen is still being sold in lots of household products as if it was perfectly safe thanks to folks who, collectively, make up what might be called the "pro-cancer lobby."

Besides all of us being exposed to Formaldehyde through consumer products, people who live in places where natural gas is being mined, like the Barnett Shale, as well as those downwind of waste-burning cement plants, like the ones in Midlothian, get dosed with more of the stuff. So, you know, we're doubly-blessed in DFW.

When the Gas Industry Says “Full Disclosure,” It Only Means 65%

According to an EneryWire analysis, "at least one chemical was kept secret in 65 percent of fracking disclosures" by companies that publicly disclosed the ingredients in their hydraulic fracturing fluid.

The study supports the claims of critics including Downwinders, that companies who say they're fully disclosing the contents of their fracking fluids aren't really doing so. Downwinders has joined other members of the Dallas Residents at Risk alliance in calling for the City of Dallas to require true full disclosure of all fracking fluids in order to better protect first responders.

The study supports the claims of critics including Downwinders, that companies who say they're fully disclosing the contents of their fracking fluids aren't really doing so. Downwinders has joined other members of the Dallas Residents at Risk alliance in calling for the City of Dallas to require true full disclosure of all fracking fluids in order to better protect first responders.

Industry claims it has a right to prevent the public, including doctors, firefighters, and police from knowing certain "trade secret" ingredients in their fracking fluids and every clearinghouse for ingredient information – including the much-heralded one established in Texas – allows for the use of this exemption. This trade use exemption is what the EnergyWire analysis tracked.

"It's outrageous that citizens are not getting all the information they need about fracking near their homes," said Amy Mall, who tracks drilling issues for the Natural Resources Defense Council. "Companies should not be able to keep secrets about potentially dangerous chemicals they're bringing into communities and injecting into the ground near drinking water."

But companies say they spend millions of dollars researching and developing new formulations of frack fluid and shouldn't have to give away their secret recipes.

"In just the past 18 months, the industry has spearheaded an effort that took us from an idea on paper about disclosure to a fully functional and user-friendly disclosure system," said Steve Everley of Energy in Depth, a campaign of the Independent Petroleum Association of America. "That kind of commitment and progress cannot be overstated in a discussion about industry disclosure."

This is very simple. If your a Dallas firefighter responding to an accident at a gas facility site, you need to know what chemicals are on site, how much of those chemicals are there, and where they're stored. No exceptions.

The High Cost of Fracking

Yesterday, Environment Texas released a new compilation report in Dallas, titled, "The Costs of Fracking." There's not a lot of new information, but it does serve as a convenient catalog of the disadvantages of inviting the gas industry to town, as the Dallas City Council is considering via a new gas drilling ordinance. Every city council member should take a look, although we doubt they will.

Yesterday, Environment Texas released a new compilation report in Dallas, titled, "The Costs of Fracking." There's not a lot of new information, but it does serve as a convenient catalog of the disadvantages of inviting the gas industry to town, as the Dallas City Council is considering via a new gas drilling ordinance. Every city council member should take a look, although we doubt they will.

The report covers the impact of fracking on public health, water, air, as well as the infrastructure demands of the gas industry. Among the tidbits:

"The truck traffic needed to deliver water to a single fracking well causes as much damage to local roads as nearly 3.5 million car trips. The state of Texas has approved $40 million in funding for road repairs in the Barnett Shale region, while Pennsylvania estimated in 2010 that $265 million would be needed to repair damaged roads in the Marcellus Shale region."

Fracking can affect the value of nearby homes. A 2010 study in Texas concluded that houses valued at more than $250,000 and within 1,000 feet of a well site saw their values decrease by 3 to 14 percent.

The average public health costs of air pollution from fracking operations in Texas’ Barnett Shale region reach $270,000 per day during the summer smog season.

Here's the press release. Here's the report.

2011 was the Worst Year for Smog since 2006 in DFW. 2012 Is One Bad Air Day Away Matching It.

Last year's air quality death spiral in DFW was sometimes explained away as an anomaly because of the severe drought the entire state was going through.

Last year's air quality death spiral in DFW was sometimes explained away as an anomaly because of the severe drought the entire state was going through.

So what's the explanation this year?

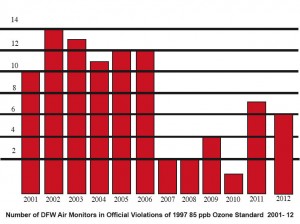

With yesterday's high ozone levels sending a 6th monitor into an exceedance of the old 1997 85 parts per billion smog standard, DFW is just one more bad air day away from matching last year's dreadful results. Today's ozone forecast says there should be no high levels of smog in DFW today, even as the temperature reaches for a record high. But then again, they weren't predicted Thursday either.

To give you some idea how rapidly things have gone downhill for air quality in DFW the past two years, just look at the annual numbers. From 2007 to 2010, we had a total of nine monitors register official exceedances of the 85 ppb standard. That's about two monitors a year average. This turns out to be the closest we've ever come to actually meeting the standard. Officials could argue with some justification that air quality was slowly getting better.

On the other hand, during the last two years, we've had 13 monitors record exceedances of the 85 ppb standard, an average of 6.5 a year, and 2012's ozone season is not yet over. You could add up all the exceedances from the four years between 2007 and 2010 and still not equal the number we've experienced in just the last 24 months.

This is not progress.

TCEQ and the gas industry have argued for some time that gas mining couldn't possibly be contributing to smog problems since smog levels were going down as drilling was increasing in DFW. But that's not true anymore. As gas drilling has moved further and further east – into the heart of the non-attainment area, we've seen in increase in ozone concentrations, in exceedances in monitors, and monitors in the eastern part of the Metromess exceeding the standard that hadn't done so in five to seven years.

Meanwhile all other major source categories for air pollution have been decreasing their emissions. Cars, power plants and cement kilns are actually releasing less air pollution now than they were ten or 20 years ago. Only one large specific source category has increased its annual tonnage significantly over that same time – oil and gas.

Is it just a coincidence that smog is getting worse as oil and gas pollution skyrocket – not only in the Barnett Shale that surrounds DFW on three sides, but by all the new oil and gas sources now southeast of Dallas as part of the Haynesville Shale play that are blowing their pollution toward us most of the ozone season? There are now so many gas compressors in Freestone County, less than 75 miles away from the Dallas County line, that their emissions represent the equivalent of over 4 new Big Brown coal plants. What do you think the impact on air quality would be of four large new coal plants located immediately upwind of DFW? Might it look a lot like it does in 2012?

Could it be that the dirty mining of "clean" natural gas is making it impossible for DFW to meet the old 85 ozone standard, much less the new 75 ppb one? That the Devil's Bargain so many former and current elected officials made with the gas operators to grab the cash and run is now coming back to bite them and us in the air quality butt? That was certainly the conclusion of the study we publicized this last Tuesday from the Houston Advanced Research Center:

"Major metropolitan areas in or near shale formations will be hard pressed to demonstrate future attainment of the federal ozone standard, unless significant controls are placed on emissions from increased oil and gas exploration and production….urban drilling and the associated growth in industry emissions may be sufficient to keep the area (DFW) in nonattainment."

It's time for local officials to replace those cash registers in their eyes with gas masks. Because of their rush to make money, they didn't pause to understand how so much new industrial activity could produce smog just like the bad ol' days. They were being paid not to understand. And now 5 to 6 million people who still can't yet breathe safe and legal air are paying the price.

Study: Gas Drilling “Significantly” Increasing DFW Smog

In the middle of another bad North Texas ozone season, a new study by a Houston research consortium concludes that Barnett Shale natural gas facilities "significantly" raise smog levels in DFW, affecting air quality far downwind.

In the middle of another bad North Texas ozone season, a new study by a Houston research consortium concludes that Barnett Shale natural gas facilities "significantly" raise smog levels in DFW, affecting air quality far downwind.

According to the study, ozone impacts from gas industry pollution are so large, they'll likely keep North Texas from being able to achieve the EPA's new 75 parts per billion (ppb) ozone standard.

Author Eduardo P. Olaguer, a Senior Research Scientist and Director of Air Quality Research at the Houston Advanced Research Center, concludes that, "Major metropolitan areas in or near shale formations will be hard pressed to demonstrate future attainment of the federal ozone standard, unless significant controls are placed on emissions from increased oil and gas exploration and production….urban drilling and the associated growth in industry emissions may be sufficient to keep the area (DFW) in nonattainment."

Olaguer's article describing his study was recently published in the July 18th edition of the Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. It's the first independent study to examine specific North Texas ozone impacts from the gas industry.

Environmental groups say air pollution from natural gas sources is already making it impossible for DFW to meet even the obsolete 15-year old standard of 85 ppb. So far in 2012, five monitors have violated that level of smog despite a state plan that Austin guaranteed would reduce ozone concentrations in DFW to record lows this year. Counting 2012's failure, DFW has been in continual violation of the Clean Air Act for its smog pollution since 1991.

"This study is proof we need a regional strategy of self-defense to reduce air pollution from the gas industry," said Downwinders at Risk Director Jim Schermbeck, whose group has been leading the fight to reduce smog-forming pollution from gas sources for two years now. "TCEQ and EPA are not doing enough to rein-in these facilities. Despite their official plans, our air is getting dirtier, not cleaner because gas pollution is still under-regulated. It's time for us to do more at the local level."

Schermbeck suggested the study could make a difference in the upcoming city council vote on a new Dallas gas drilling ordinance.

"Dallas has a chance to react positively to this new evidence by adopting the nation's first policy aimed at mitigating the tons of new pollution caused by gas mining in its new drilling ordinance. That would be a very large step forward in advancing regional clean air goals."

A city-wide coalition of neighborhood, homeowners, and environmental groups has been urging the Dallas city council to require gas operators to reduce as much air pollution as they release through funding of anti-pollution measures across the city. The Houston Center study gives them a lot of fresh arguments.

According to it, "…oil and gas activities can have significant near-source impacts on ambient ozone, through either regular emissions or flares and other emission events associated with process upsets,and perhaps also maintenance, startup, and shutdown of oil and gas facilities."

In fact, just routine emissions from a single gas compressor station or large flare can raise ozone levels by 3 parts per billion as far as five miles downwind, and sometimes by 10 ppb or more as far as 10 miles downwind.

Those impacts rival the size of smog effects traced back to the Midlothian cement kilns or East Texas coal-fired power plants by previous studies.

As the study notes, "Given the possible impact of large single facilities, it is all the more conceivable that aggregations of oil and gas sites may act in concert so that they contribute several parts per billion to 8-hr ozone during actual exceedances."

This conclusion directly contradicts the stance of the Natural Gas industry and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, both of which deny that Barnett Shale gas emissions are large enough or located in areas that can influence DFW ozone levels.

But the Houston study is based in part on data collected by industry, as well as information from the city-sponsored "Fort Worth Study," and citizen-sponsored testing in the town of DISH in Denton County. It also uses a kind of computer modeling that allows for a more realistic understanding of how large releases from gas facilities can increase ozone pollution than the one the TCEQ uses. It's the most sophisticated challenge yet to the state and industry's claim that gas emissions do not constitute a large threat to DFW air quality.

"This is reality-based science, not the ideologically-influenced happy talk that's coming out of TCEQ these days," said Schermbeck. "Local governments in North Texas, especially those that are traditional allies of clean air, need to pay close attention and act on it."

The report is available for downloading here.

The EPA Loss in Court You Didn’t Hear About, But Could Affect You More in DFW

Let's face it, the EPA legal team has taken a bunch of hits lately. Losses in court over the Texas Flex permitting plan and national cross state pollution rules, among others, have gotten lots of headlines, but for various reasons may not be as awful as they first sound to environmentalists.

Let's face it, the EPA legal team has taken a bunch of hits lately. Losses in court over the Texas Flex permitting plan and national cross state pollution rules, among others, have gotten lots of headlines, but for various reasons may not be as awful as they first sound to environmentalists.

But there was a recent ruling that did hit home for metropolitan areas like DFW that are a) already in "non-attainment" of the federal ozone, or smog, standard, and, b) host lots of urban gas and oil drilling. You probably didn't hear about it, but it may have more of an impact on your air here because it once again left a large loophole in current law that allows the oil and gas sector to escape emissions "off-setting."

According to the Clean Air Act, every large industry that comes to set up shop in a non-attainment area like DFW must decrease as much pollution as it estimates it will increase. This is required so that new pollution doesn't just take the place of pollution that's been reduced from industries already operating in the area. Otherwise, there would be a large imbalance between new industries and established ones that would put air quality progress in peril.

And that's exactly what's happening in DFW.

For a decade now, gas mining in the Barnett Shale has added tons and tons of new air pollution to the North Texas airshed that has not had to be off-set with reductions. While emissions from this industrial sector grew, pollution from local cars, power plants and cement kilns actually decreased. Based on past experience DFW should be making headway toward cleaner air. But we're not. For the last two years, DFW air quality progress has stagnated and even begun rolling backwards. This year we already have five monitors out of compliance with a 1997 ozone standard, compared to just one in 2010.

So why aren't gas emissions subject to Clean Air Act "off-sets" just like a power plant or cement kiln? Because nobody writing the Clean Air Act in 1970, or its amendments in 1991, anticipated urban drilling on the scale we're experiencing it in DFW these days. Nobody foresaw the establishment of a huge gas patch in a large metropolitan area with connected, but widely diffused sources of emissions spread out over hundreds of square miles. They were thinking about "stationary sources" of pollution like coal-fired power plants, refineries and the like. The amounts needed to trigger off-setting are all oriented toward these massive facilities, not lots of smaller sources that eventually equal or surpass their output. As a result, there's a huge loophole that keeps the oil and gas industry from being regulated like any other industry in a non-attainment area.

EPA has recognized this loophole and tried to close it by ruling that facilities connected by process in the gas field may be treated as one large source of pollution – the term is "aggregate." And this is the definition that a court recently shot down in a Michigan case:

"The Cincinnati, Ohio-based 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday that EPA had no basis to find that the natural gas sweetening plant and sour gas production wells owned by Summit Petroleum Corp. in Rosebush, Mich., are "adjacent" under the statute and therefore a single source just because they shared some similar functions.

It is an important case for the oil and gas industry because it is the first appeals court ruling to address a recent EPA move seeking to more aggressively "aggregate" various nearby sources of air pollution at oil and gas facilities for permitting purposes.

The court ordered EPA on a 2-1 vote to consider again whether the facilities, spread over a 43-square-mile area, are "adjacent" under the "plain-meaning of the term," which focuses only on physical proximity."

Just in case there was any doubt about why the gas industry was challenging the EPA policy of aggregating, the next sentence of the article makes it clear:

"Industry groups object because it can bring the individual sources under the umbrella of more stringent Clean Air Act permitting requirements."

Now, of course adjacent in common law means next door. But what does it, or should it mean, in environmental law? The collective air pollution being generated by that 43 square mile complex could very well be "adjacent" to your lungs a short distance downwind. But the court didn't see it that way.

That means that going into the next clean air plan for DFW – one that will, at least theoretically be aimed at the new 75 parts per billion ozone standard – EPA will not be able to "off-set" the large amounts of air pollution generated by gas mining and processing in the North Texas non-attainment area.

And that's why we have to do it ourselves, one city and one county at a time. Starting in Dallas. Starting now.

As part of the larger re-writing of the Dallas gas drilling ordinance, a very large and impressive coalition of homeowners groups, neighborhood associations, and environmental organizations have all endorsed the idea of Dallas requiring local off-sets for any pollution released by new gas facilities within the city limits. A company would have to pay for projects that would reduce as much pollution as it was estimated to release every year. Dallas would be the first city in the country to adopt such a policy, but it probably wouldn't t be the last. And it wouldn't take that many before you started seeing an impact on industry's emissions.

We have a model in the successful Green Cement Campaign of the last half decade, that also started in the Dallas City Council chambers with a first-in-the-nation vote. All it took was a dozen cities and counties passing green cement procurement ordinances to get the cement industry's attention. As of 2014, something like 300,000 tons of air pollution a year will have been eliminated because there are no more dirty wet kilns in North Texas.

We can do it again. This time with gas patch pollution. We have to. Nobody else is going to do it for us.

Gas Industry Cites Decreasing CO2, Forgets About Increasing Methane

Maybe you've seen the headlines over the last couple of days. US Carbon Dioxide (CO2) emissions reached an historical 20 year low in the first quarter of 2012. The Federal Energy Administration attributed this decline to three factors: a mild winter, less travel, and gas-powered utility plants replacing coal-fired ones. Whereas coal was producing about 50% of America's electricity in 2005, it's only contributing 34% now, with most of that slack now being taken up by gas-generated electricity.

Maybe you've seen the headlines over the last couple of days. US Carbon Dioxide (CO2) emissions reached an historical 20 year low in the first quarter of 2012. The Federal Energy Administration attributed this decline to three factors: a mild winter, less travel, and gas-powered utility plants replacing coal-fired ones. Whereas coal was producing about 50% of America's electricity in 2005, it's only contributing 34% now, with most of that slack now being taken up by gas-generated electricity.

Gas industry representatives were quick to take credit for the reduction and use it has proof of how climate-friendly natural gas is. But they forgot something important when they did that. They didn't weigh the increase in methane releases caused by gas mining against the decrease in CO2 pollution. Methane doesn't have the lifespan of CO2 in the atmosphere, but pound per pound in the short-term, it's 25 times more potent in its climate change impact. According to climate scientist Michael Mann of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University, “We may be reducing our CO2 emissions, but it is possible that we’re actually increasing the greenhouse gas problem with methane emissions.”

Gas Patch Pollution Linked to First Alamo City Ozone Violation

Ever since smog was an issue in Texas starting in the last 1980's, the two largest metropolitan areas have been duking it out for worst air in the state. Houston was the undisputed champion for awhile, but as of the last couple of years, Dallas-Ft. Worth has been neck and neck, and last, year, even posted worse numbers than Bayou City. No other city even came close.

Ever since smog was an issue in Texas starting in the last 1980's, the two largest metropolitan areas have been duking it out for worst air in the state. Houston was the undisputed champion for awhile, but as of the last couple of years, Dallas-Ft. Worth has been neck and neck, and last, year, even posted worse numbers than Bayou City. No other city even came close.

Until now.

For the first time ever, San Antonio has a monitor in violation of the national ozone standard. It's the new standard of 75 parts per billion, so it's still way ahead of Houston and Ft. Worth that are still have chronic problems meeting the old 1997 85 ppb standard. But it's still a milestone.

What factors helped push SA over the line? Well, theres the significant growth of the larger metropolitan area itself, and out-of-state power plants that will now not be better controlled because of Team Perry's victory over the cross state pollution rules, and oh yeah, gas patch air polluion from the Eagle Ford Shale that's up wind of San Anontio:

"Increased air pollution from the oil and gas boom of the Eagle Ford Shale is believed to be a factor, in addition to local sources and pollution coming from Mexico, East Texas and the East Coast."

Study Links Utah’s “Wintertime Ozone” with Gas Patch Pollution

The rural Unita Basin in Utah has had some of the worst smog in the nation – in the middle of winter, with snow on the ground. That's not supposed to happen, but 10,000 gas wells, along with car and truck traffic combine to make it happen. A new $5 million study confirms that the smog-forming gas patch pollution is a major cause. "That seems to be a pretty strong link," said the study's main researcher.

The rural Unita Basin in Utah has had some of the worst smog in the nation – in the middle of winter, with snow on the ground. That's not supposed to happen, but 10,000 gas wells, along with car and truck traffic combine to make it happen. A new $5 million study confirms that the smog-forming gas patch pollution is a major cause. "That seems to be a pretty strong link," said the study's main researcher.

Isn't the fact that there's that a smog problem in rural Utah where none existed before fracking began sufficient evidence of the link between fracking and smog to warrant cities already suffering smog problems like Dallas to take precautions before the open the door to fracking in the city limits?