Environmental Justice

COVID CONNECTIONS

Downwinders At Risk was already dedicated to fighting for environmental health in North Texas before the COVID virus hit.

Focusing on harmful Particulate Matter, we were already supporting grassroots efforts to reduce the air pollution burdens in predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods.

We were already building out local capacity to monitor DFW air pollution and advocating an increased role for local cities and counties to protect their residents from environmental health threats.

All of that work was important before March. It’s become more important since then. But our responsibilities on the ground are outstripping our ability to support them adequately. Like other non-profits, the virus has made it harder to do even the simple things.

This week you can help provide some relief.

The Peace Development Fund has chosen to spotlight the COVID-connected work Downwinders is doing, along with that of 12 other grassroots groups across the country to help supplement their budgets during the crisis. The Fund and generous donors are matching every dollar we raise this week up to $10,000 – that’s a $20,00,000 grant on the line.

We have until Friday to raise the $10,000.

Beginning today and continuing thru Tuesday the 5th at Midnight you can help us meet this goal by contributing via our North Texas Giving Day Page.

Then Wednesday thru Friday the Development Fund has its own Downwinders Mighty Cause pay portal you can also use.

We’re using each day this week to show how our various pieces of program work is more relevant than ever before. Today it’s an update on our ambitious new DFW air monitoring network – SHAREDAIRSDFW.

We know everyone is having a hard time, but with the Development Fund matching your dollars, you can make whatever contribution you give go twice as far to benefit those at highest risk.

Thanks for your support,

Evelyn Mayo, Chair

COVID Connects:

Vulnerable Communities to the Need

for Better Air Pollution Monitoring

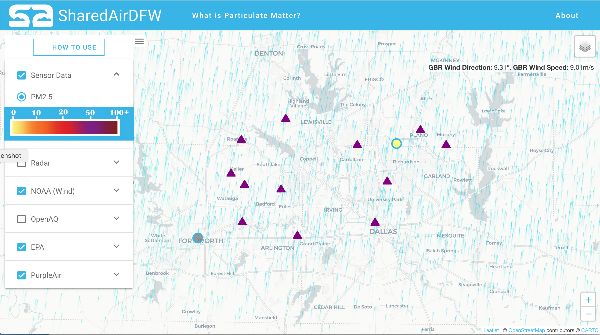

A screenshot of the SHAREDAIRDFW network map being assembled by UTD students and Downwinders at Risk. This map will soon be available at websites hosted by UTD, Dallas County and Downwinders, Only two of the over 100 new monitors are installed (dots) but more are on their way.

What is It?

The SHAREDAIRDFW community air quality monitoring network.  With its partners at UTD, Downwinders is building a new air monitoring network for DFW that will provide real time information from over 100 locations, including industrial hot spots in Joppa, West Dallas and Midlothian.

With its partners at UTD, Downwinders is building a new air monitoring network for DFW that will provide real time information from over 100 locations, including industrial hot spots in Joppa, West Dallas and Midlothian.

Why Do It?

Dallas County’s 2.7 million residents currently share only one EPA  Particulate Matter air pollution monitor, north of downtown. Tarrant County has two and Denton County one. These monitors only reflect very local conditions and don’t reveal pollution levels in “frontline” neighborhoods where industry operates next to homes.

Particulate Matter air pollution monitor, north of downtown. Tarrant County has two and Denton County one. These monitors only reflect very local conditions and don’t reveal pollution levels in “frontline” neighborhoods where industry operates next to homes.

Making pollution burdens more equitable across racial and class lines requires identifying, measuring, and mapping those burdens: “You can’t fix what you don’t measure.” The SHAREDAIRDFW network is the first attempt to permanently map air pollution burdens across North Texas and make that information easily accessible to the public 24/7.Dallas County’s 2.7 million residents currently share only one EPA Particulate Matter air pollution monitor, north of downtown. Tarrant County has two and Denton County one. These monitors only reflect very local conditions and don’t reveal pollution levels in “frontline” neighborhoods where industry operates next to homes.

Making pollution burdens more equitable across racial and class lines requires identifying, measuring, and mapping those burdens: “You can’t fix what you don’t measure.” The SHAREDAIRDFW network is the first attempt to permanently map air pollution burdens across North Texas and make that information easily accessible to the public 24/7.

What’s the COVID Connection?

Research being done during the COVID pandemic concludes those living with the highest air pollution burdens are among the most vulnerable to being infected and dying from it. Specifically there seems to be a connection between a person’s exposure to Particulate Matter and Nitrogen Oxide air pollutants and the likelihood of contracting COVID. Past studies from the SARS epidemic also point to a strong link between exposure to air pollution and vulnerability to illness.By mapping where the heaviest air pollution burdens are, we can avoid adding to that burden and pursue policies targeting pollution decreases. We can begin to reverse the circumstances that makes the most pollution-impacted neighborhoods the most vulnerable to disease.

STATUS?

Via teleconferencing, UTD students are finishing up the digital map the Network  will use to display its real time air quality information. This map is meant to display not only the levels recorded by our own fleet of monitors, but easy access to the handful of EPA and Purple Air monitors in DFW as well.

will use to display its real time air quality information. This map is meant to display not only the levels recorded by our own fleet of monitors, but easy access to the handful of EPA and Purple Air monitors in DFW as well.

The map will be hosted on websites hosted by UTD, Dallas County and Downwinders.The first community monitors are slated for the former Freedman’s town of Joppa, where Downwinders bought a utility pole for the installation of the larger Mothership monitor. We’ve got a contract for Internet service and are now trying to tie down electrical power.

After a planned community meeting in March was canceled, we’re now gearing back up to find hosts for all ten “satellite” monitors. We hope to be able to begin operat ion this summer.Once we’re up and running in Joppa, West Dallas is next and then Midlothian. In all Downwiwnders will be responsible for 33 of the over 100

ion this summer.Once we’re up and running in Joppa, West Dallas is next and then Midlothian. In all Downwiwnders will be responsible for 33 of the over 100 network monitors going up as part of the first wave installation.

network monitors going up as part of the first wave installation.

……MEANWHILE, Downwinders is using its portable monitors to record air quality in front line neighborhoods during the shelter-in-place periods so we’ll have a baseline for what cleaner air looks like.

The Only Thing Missing in Dallas’ Climate Plan “Focus on Equity” is…any measure of Equity

A staff presentation focusing on Dallas environmental equity lacks any metrics for comparing residential pollution burdens, or even for measuring the success of its own outreach effort.

So how does City Hall know what environmental “equity” looks like?

According to management guru Peter Drucker, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.”

Then what does it mean that a full year into a Dallas climate planning process heavily touted as reflecting the city’s emphasis on “equity” there’s still no map showing how pollution burdens are distributed across Big D? And what does it tell you when a presentation meant to advertise the inclusiveness of the City’s outreach effort for its climate plan doesn’t document participation by residents of color?

It tells you that despite all the rhetoric on the subject, Dallas City Hall isn’t serious about environmental justice yet.

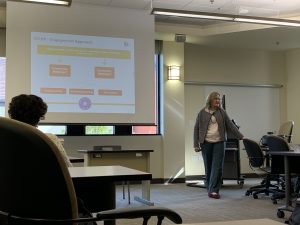

Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability Susan Alvarez presents the City’s climate plan through “an equity lens.”

Exhibit A: “Dallas’ Climate Action Through an Equity Lens.”

This was a presentation that Susan Alvarez, Assistant Director of the City of Dallas Office of Environmental Quality & Sustainability, gave as part of Eastfield College’s Sustainability as a Social Justice Practice: Developing Resilient Strategies held last Friday, November 8th.

Context is everything and so it’s important to note that the entire thrust of both the Conference and the City’s specific presentation was aimed squarely at how to respond to current environmental challenges in an equitable and just way. Here was a chance for Dallas OEQS city staff to display their embrace of equity as it relates to the climate plan it’s been paying a half-million dollars to consultants to construct. It was their very own EJ report card.

Equity and the Climate Plan:

And sure enough, there was no turning away from Dallas’ racist history in Alvarez’ presentation. Maps showing the City’s chronic segregation and poverty were included, as well as allusions to the Trinity River as the city’s dividing line between Haves and Have-Nots. Alvarez spoke about the current “Redlining Dallas” exhibit at City Hall that traces the City’s history of racism across 50 feet of photographs and stories.

In fact, just about every impact of the City’s official segregation was referenced, except for the one you’d expect.

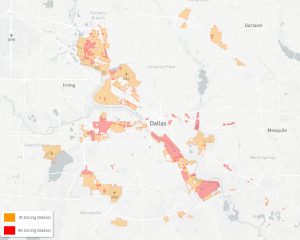

There was not a single slide or sentence expended on the disproportional environmental impacts of 100 years or more of Dallas racism. No maps of where heavy industry zoning is allowed in the City. No maps of where most of the City’s largest polluters are located. No maps of what zip codes or Council Districts have the highest pollution per capita numbers. No references to past environmental justice struggles with the City like the West Dallas RSR fight, or gas drilling.

Watching the presentation you’d get the impression that racism infected every aspect of life for Dallas residents of color except for their exposure to pollution. But of course, we know that’s not true.

During this and other presentations on the climate plan-in-progress, staff go out of their way to point out that industry makes up “only 8% of emissions.” But if you’re interested in applying “equity” to this number the next slide should show the audience where that industry is distributed in Dallas – a map showing you where industrial polluters are allowed to set-up shop. A slide to show you the amounts of permitted pollution by Zip Code, or maybe actual 2017-18 emissions by Council District. But there is no next slide.

If there were, it would show that most of that industry is located in predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods. Racist zoning is at the heart of not just banking, education, and employment inequities in Dallas. It also means the dirtiest industries have always been located in close proximity to people who were institutionally considered Second-Class citizens.

This one slide is already more information on Dallas environmental equity than you’ll find in the entire City staff presentation on equity and the climate plan

Disproportional exposure to industrial pollution by residents of color is not just AN equity issue. It’s THE single most important equity issue when you’re speaking about environmental justice in Dallas. The City’s Black and Brown residents are more likely to be exposed to harmful pollution than their white peers because the City’s own zoning designed it that way – but you’d never know it watching this presentation, on equity, at the social justice conference.

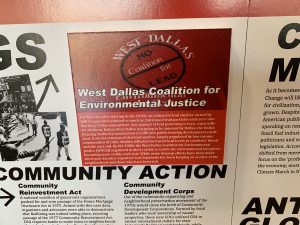

The “Redlining Dallas” exhibit that Alvarez cited thinks so. Along with other insidious effects of racism, it gives space to the RSR clean-up fight Luis Sepulveda and his West Dallas Coalition for Environmental Justice waged in the early 1990’s. But there was no mention of that fight or any other Dallas examples during the presentation on equity, at the social justice conference.

Staff referenced every other kind of red-lining on display at the City Hall exhibit – except the one most relevant to the topic.

Nor was there any mention of how much industry was located in the Trinity River floodplain, doing business in Black and Brown neighborhoods founded because the City wouldn’t allow these so-called “undesirables” to live anywhere else but side by side with “undesirable” industries. Alvarez made the point in the presentation that climate change means more flooding in general and more severe flooding. The next slide should show who and what is affected by that new flooding risk. A slide showing what percentage of heavy industry is located in the flood plain. A slide showing what the racial make-up and income levels are of those who’ll be more affected by increased flooding…and contamination. But there was no next slide, in the presentation on equity, at the social justice conference.

If you don’t have accurate maps of the inequities plaguing the status quo, how do you know when or if you’re ever getting rid of them? How do you judge success without a baseline?

PR, Process and Equity:“I don’t think it’s important to say I’ve got four black people in my stakeholders group.”

Alvarez lowered expectations for the presentation by saying it would only look at the question of equity in how it was applied to the City’s climate plan “community engagement.” No actual equity policy options from other plans were on the table, just how well the plan’s public relations campaign did.

Not very well, she admitted. In fact the initial meetings and publicity were so anemic that she said the professional PR folks at Earth X had a come-to-Jesus-meeting with staff about a reboot. So that’s tens of thousands of dollars wasted on PR consultants only to be usurped by better free advice from locals.

A meeting of the Dallas climate plan advisory group.

In her recounting of the climate plan’s PR rollout and planning process Alvarez gave an overview of the mechanics. “X” number of meetings attracted “X” numbers of people. The City’s survey got “X” number of responses. An “X” number of people serve on an advisory stakeholders group.

Considering the very specific circumstances of the presentation, the next slide should have been how the results of those attending meetings, or completing a surveys, or advisory committee memberships reflect Dallas’ population as a whole. How do we stack up to who we’re representing? According to the Statistical Atlas Dallas is approximately 25% Black, 41% Hispanic , 30% White and 3% Asian. So the next slide should compare what percentage of those attending climate plan meetings, or completing surveys, or becoming advisory committee members were Dallas residents of color vs the city demographics.

But there was no next slide about how inclusive the City’s climate plan community outreach or advisory process has been in the presentation on equity, at the social justice conference.

In response to a question about the lack of such information Alvarez said it was irrelevant to the topic at hand. “I don’t think it’s important to say I’ve got four black people in my stakeholders group.”

Since the advisory group membership is only listed online by organizational affiliation it’s impossible for anyone outside the meetings to know what the ethnic or gender make-up of it is. There are 39 separate entities listed. 25% of that number would be nine to ten black people.

In elaborating, Alvarez challenged the idea that mapping Dallas’ racial or ethnic disparities in pollution  burdens was necessary to understanding “Dallas’ Climate Action Through an Equity Lens.” She more or less stated it didn’t matter. (the presentation was recorded by Eastfield College and Downwinders has asked for access to it in order to quote Alvarez accurately).

burdens was necessary to understanding “Dallas’ Climate Action Through an Equity Lens.” She more or less stated it didn’t matter. (the presentation was recorded by Eastfield College and Downwinders has asked for access to it in order to quote Alvarez accurately).

Nothing could better summarize the kind of Catch-22 “don’t confuse me with the facts” approach to “equity” the City staff has taken in regards to environmental racism than the belief that actual data about Dallas environmental racism is of no use to the study or remedying of Dallas’ environmental racism.

And nothing makes a better case for the need to pass environmental justice reforms the Southern Sector Rising Campaign is advocating at Dallas City Hall, including an environmental justice provision in Dallas’ economic development policy, restoration of the Environmental Health Commission, and creation of a Joppa Environmental Preservation District. If residents want environmental equity considered in city policy they’re going to have to enlist their City Council members, do it themselves, and enact reforms like these.

The same is true as City Hall ramps up to take on citywide land-use planning in its “forwardDallas!” process early next year. When staff recently released the City’s “equity indicators” report, there was an indicator for everything but the environment. It only reinforced the idea that the environment, and environmental justice, are still after-thoughts in Dallas city government. Residents will have to arm themselves with the information the City staff can’t or won’t provide. They should start with the recent Legal Aid report “In Plain Sight” that demonstrates deep neglect for code and zoning regulations in Southern Dallas.

And it also goes for the climate plan. Southern Sector Rising’s first recommendation for the city’s climate plan last May was “Remove industrial hazards from the flood plain.” On the other hand, the idea of land use reforms in the floodplain hasn’t appeared in any official literature or presentation associated with the city’s climate plan.

Grist recently published an article about the Providence Rhode Island climate planning process that looks to be the exact opposite of the model Dallas has adopted. But that city benefited from having an environmental justice infrastructure already in place when the climate crisis assignment arrived. Where’s the home for Environmental Justice in Dallas City Hall? Right now, it’s with staff that doesn’t think metrics about equity are important, in its presentation on equity, at the social justice conference.

Listen to Our New Chair Get Interviewed By D Magazine

Downwinders at Risk’s new Chair Evelyn Mayo gets a huge shout out in D magazine’s popular online manifestation with her very own “Earburner” podcast.

D magazine reporter Matt Goodman and D Managing Editor Tim Rogers interview Evy about her new report on Southern Dallas zoning for Legal Aid, her Roller Derby years in Singapore, and of course, Particulate Matter.

CLICK HERE to link to the podcast and learn more about one the new dynamic leaders of Downwinders at Risk.

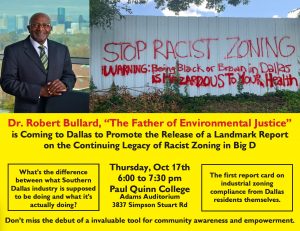

Dr. Robert Bullard in Dallas Oct 17th at Paul Quinn to Unveil New Report

Environmental Justice issues in Dallas will get a higher profile next week as the “Father of Environmental Justice” comes back to Big D to help promote the release of a new landmark report on zoning in Southern Dallas.

Texas Southern University’s Dr. Robert Bullard is no stranger to DFW, having included a chapter on the struggle to get the West Dallas RSR lead smelter Superfund Site cleaned-up in his 1994 book “Unequal Protection.” But it was 1990’s “Dumping on Dixie” that’s widely recognized as the very first comprehensive look at what he termed “environmental racism” in the US – how rural Southern communities of color became national dumping grounds.

Texas Southern University’s Dr. Robert Bullard is no stranger to DFW, having included a chapter on the struggle to get the West Dallas RSR lead smelter Superfund Site cleaned-up in his 1994 book “Unequal Protection.” But it was 1990’s “Dumping on Dixie” that’s widely recognized as the very first comprehensive look at what he termed “environmental racism” in the US – how rural Southern communities of color became national dumping grounds.

Dr. Bullard returns to Dallas on Thursday October 17th for a full day of appointments and visits concluding with a presentation that evening at Paul Quinn College of a new Legal Aid of Northwest Texas report on the continuing impact of racist land use policy in Dallas’ “Southern Sector.”

Entitled “In Plain Sight” this Legal Aid effort is a blockbuster.

It’s the first close-up look at industrial zoning in Southern Dallas, comparing what’s on the books versus what’s actually taking place on-site. And it’s Dallas residents themselves who did the investigation, with teams of unofficial neighborhood inspectors visiting each site, taking pictures, and recording observations. In effect, it’s a citizen report card on the City’s enforcement of its own land use policies in the most neglected, abused parts of Dallas.

Inspired by the example of the now notorious Shingle Mountain illegal dump, which was allowed to operate by the City of Dallas without either the correct Certificate of Occupancy or the correct zoning, the study finds there are plenty of other examples of this kind of “non-compliance” throughout Southern Dallas. In fact, violation rates were found to be extremely high in some neighborhoods. It’s Exhibit A for why there must be systematic zoning reform in Dallas.

There are lots of events happening on the17th, but you really don’t want to miss the roll-out of this important, game-changing report and a chance to meet and talk to a living legend.

Marsha Jackson standing in her backyard

Update: A 21st Century Regional Air Monitoring Network for DFW is On Its Way

me technical and bureaucratic hitches, momentum is starting to build toward the 2020 operation of a true 21st Century DFW regional air quality monitoring network.

me technical and bureaucratic hitches, momentum is starting to build toward the 2020 operation of a true 21st Century DFW regional air quality monitoring network.

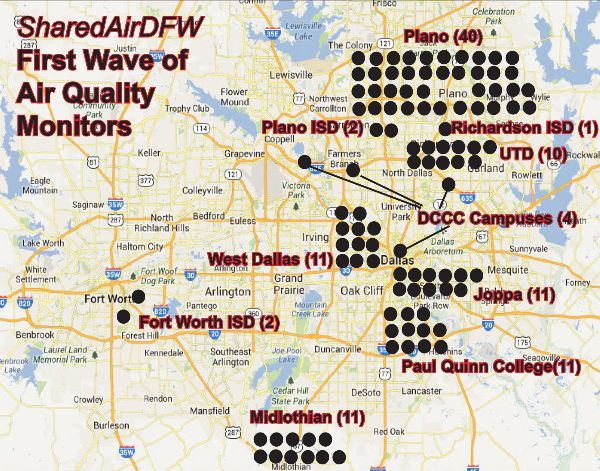

A small army of University of Texas at Dallas graduate students are assembling over 100 solar-powered wireless air monitoring units to be dispersed throughout the metro area. A third of those have been purchased by Downwinders for placement in Joppa, West Dallas, and Midlothian. 40 or more or going to Plano. Three Dallas County Community College campuses are receiving one, along with the Fort Worth and Richardson school districts.

And now news has come that Paul Quinn College has received an EPA grant to purchase 11 of these monitors for placement around its Southern Dallas campus. Downwinders is working to coordinate the location of its Joppa area monitors with Paul Quinn to provide Southern Dallas with its own mini-network of monitors.

Meanwhile another group of UTD students are working on the mapping software and app residents will be able to use to access the data in real time. They’re being led in this effort by Robert “The Map” Mundinger, who Downwinders hired for the job. All in all, Downwinders has now invested almost $50,000 in this network, which we hope will become a model for the rest of Texas and the nation.

Texas Misusing 17-Year Old Rural Air Pollution Model to Permit Inner-City Joppa Asphalt Plant

One of these is not like the other

What if you found out an industrial polluter was operating in your densely-populated neighborhood and the state told you not to worry because an obsolete computer model of the polluter’s releases 17 years ago and 500 miles away, in a desert, performed by the polluter themselves, said everything was OK?

That’s exactly the situation Joppa residents find themselves in as the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) goes through the motions of renewing one of the permits of the many industrial polluters located in the community.

Austin Industries’ asphalt batch plant sits next to the Marietta Martin (TXI) concrete batch plant in Joppa, and both are in the Union Pacific switch yard and all of those are adjacent to the giant Tamko asphalt roofing factory.

Austin Industries’ asphalt batch plant sits next to the Marietta Martin (TXI) concrete batch plant in Joppa, and both are in the Union Pacific switch yard and all of those are adjacent to the giant Tamko asphalt roofing factory.

Austin has applied to the TCEQ for a renewal of its 10-year old air permit for its Joppa plant and gave notice last December. Legal Aid of NorthWest Texas requested a contested case hearing on behalf of the Joppa Freedman’s Town Association and Downwinders at Risk requested one on behalf of resident Jabrille McDuffie.

To absolutely no one’s surprise, TCEQ’s Executive Director recommended against such a hearing at the beginning of August in comments mailed out to all parities. He argued that contrary to the opponent’s claims there was sufficient evidence that Austin Industries permit in Joppa was following the law and was “protective of human health.” Previous “air quality analysis,” the Executive Director says, have concluded such already.

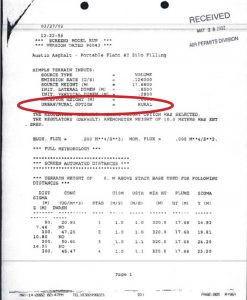

The entire basis of that “air quality analysis” is the computer air modeling performed by Austin Industries’ hired contractors and supposedly double-checked by the state…in 2002.

Just like any other computer model, it all depends on the variables: volume of air pollution, local meteorology, stack height, local “receptors” aka people or animals who live by or near the facility, and even local terrain. Winds do one thing to air pollution on the open plains and another in the middle of a city block.

Because of these variables, an Exxon refinery that wants to build a facility in Houston with the exact same design as is has in Arkansas still has to submit a separate computer model to account for the distinct surroundings in the new location. The one from Arkansas just won’t do for Houston.

Or at least that’s the way things are supposed to work. But like so much else in Southern Dallas these days, things aren’t working the way they’re supposed to.

According to the TCEQ the Austin Asphalt facility is a portable asphalt batch plant operation. That means it wasn’t built specifically for its current Joppa site. It was moved there and it can be moved somewhere else.

In 2002 it first operated in Hockley County, a rural part of Northwest Texas near Lubbock some 400 miles west of Joppa. It moved to its current location in Joppa in 2008.

In 2002 the TCEQ let Austin Industries use what’s called a “SCREEN3” air model to determine if the air pollution from its asphalt batch plant’s was a threat to anyone in Hockley County. Again unsurprisingly, the firm hired by Austin Industries to do the computer modeling found it was “protective of human health.”

TCEQ says the Austin Industries’ asphalt plant has never been subject to any additional “impacts evaluation.” besides this 2002 review.

That means the only air modeling ever done for this Austin asphalt plant was while it was operating in rural Hockley County in 2002. There has been no air modeling of the plant since it came to Joppa in 2008.

In 2002 the Austin plant was in West Texas and used a rural air model. In 2019 they’re still using for it for operation in Joppa.

Besides the most obvious and important difference in population density between unincorporated Hockley County near Lubbock and inner city Dallas, all of the variables in the 2002 modeling apply only to the Hockley County location. Meteorology, stack height, and surrounding terrain among them. In fact, the entire model was defaulted to a “rural” versus “urban” option in 2002. This renders the modeling scientifically useless in its current location in Joppa.

But that uselessness isn’t keeping the Executive Director of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality from citing it to justify renewal of Austin’s air permit.

There’s also the matter of the age and limitations of the SCREEN3 model. In 2011 EPA replaced it with something called the “AERSCREEN” model. In doing so the agency called the old model “outdated“ and said “there are no valid reasons” to keep using SCREEN3.

And it’s not just the EPA. State environmental agencies, like the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, have quit accepting SCREEN3 modeling.

Alex De Visscher, Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in Air Quality and Pollution Control Engineering at the University of Calgary, writing in an 2013 text book entitled “Air Dispersion Modeling: Foundations and Applications,” said SCEEN3 is a “product of a previous generation of air dispersion modeling” and “is no longer a recommended model… it does not allow for multiple sources, and it does not include atmospheric chemistry or deposition.”

These exclusions are important. There are multiple sources of Particulate Matter 2.5 air pollution at Austin Industries’ plant in its Joppa location, including piles of raw material, and industrial combustion at the site. SCREEN 3 modeling didn’t and wouldn’t reflect these multiple sources of pollution. And of course when you’re talking about PM 2.5 pollution, as you are with an asphalt batch plant, the atmospheric chemistry and deposition, or fallout, is critical.

TCEQ’s own air modeling guidelines say so:

“Air dispersion models utilize dispersion coefficients to determine the rate of dispersion for a plume. Dispersion coefficients are influenced by factors such as land-use / land-cover (LULC), terrain, averaging period, and meteorological conditions. Evaluating the LULC within the modeling domain is an integral component to air dispersion modeling. The data obtained from a LULC analysis can be used to determine representative dispersion coefficients. The selection of representative dispersion coefficients may be as simple as selecting between rural or urban land-use types. For the ISC, ISC-PRIME, and SCREEN3 models, the dispersion coefficients are based on whether the area is predominately rural or urban. The classification of the land use in the vicinity of sources of air pollution is needed because dispersion rates differ between rural and urban areas.”

The TCEQ itself says it makes a fundamental difference whether the air model for a polluter is run for urban or rural terrain. Yet for over a decade TCEQ and Austin Asphalt have misused the results of a “rural” computer model to misleadingly assure inner-city Joppa residents that the company’s asphalt plant posed no harm.

What’s more, the modeling performed in 2002 only examined “asphalt vapors,” a made-up, vague pollutant category that can’t be monitored or measured. It didn’t examine Particulate Matter 2.5 pollution or specific Volatile Organic Compounds that make up those “vapors” and was therefore incomplete in the extreme.

So despite all the verbage the TCEQ’s Executive Director uses to tell Joppa residents th at past “air analysis” has shown Austin Industries’ plant to be protective of human health, in truth the only “analysis” ever done was performed 17 years ago in a sparsely-populated rural location 400 miles away from its current location, with what TCEQ admits are totally inaccurate modeling inputs by company consultants. It didn’t include all priority pollutants or even all sources of air pollution from the facility and the model used is now considered obsolete by EPA, modeling experts, and other state environmental agencies.

at past “air analysis” has shown Austin Industries’ plant to be protective of human health, in truth the only “analysis” ever done was performed 17 years ago in a sparsely-populated rural location 400 miles away from its current location, with what TCEQ admits are totally inaccurate modeling inputs by company consultants. It didn’t include all priority pollutants or even all sources of air pollution from the facility and the model used is now considered obsolete by EPA, modeling experts, and other state environmental agencies.

Joppa residents deserve better.

In its response to the Executive Director, Downwinders at Risk specifically requested TCEQ delay further regulatory action on this permit renewal until it can conduct a modern comprehensive air modeling impact analysis for Austin Asphalt’s current operation in Joppa that requires an evaluation of all on-site sources of pollution, including fugitive and mobile sources, on the Austin Asphalt site, off-site near-by sources of pollution within a three kilometer (1.86 mile) radius of Austin Asphalt’s facility, and representative monitored background concentrations obtained from local Joppa neighborhood monitoring as well as modeling of permitted maximums emission rates form all sources.

On September 11th the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality will take up the Austin Industries permit renewal at its headquarters in Austin. Both Legal Aid and Downwinders at Risk representatives will be present to answer any questions from the Commissioners but will not be allowed to make any statements. We’ll let you know the outcome.

One might reasonably ask why the City of Dallas itself isn’t fighting this permit renewal? After all in 2007, the city took on a string of proposed coal-fired power plants that it said would increase air pollution for Dallas. But to date that same city has never bothered to try and stop an industrial polluter from opening shop or renewing its permit in one of its most abused neighborhoods.

might reasonably ask why the City of Dallas itself isn’t fighting this permit renewal? After all in 2007, the city took on a string of proposed coal-fired power plants that it said would increase air pollution for Dallas. But to date that same city has never bothered to try and stop an industrial polluter from opening shop or renewing its permit in one of its most abused neighborhoods.

This dishonest use of a irrelevant model by the state’s discredited environmental agency shows why it’s imperative the City of Dallas – and all municipalities in Texas – change the way they do business and be proactive in addressing their environmental justice and environmental health issues in their own city limits.

Too often city representatives default to state or federal officials on the environment when they should be the first line of defense, not the last. City officials’ reliance on a failed state agency to perform its job as environmental protector is what caused Shingle Mountain. It’s what caused this situation in Joppa. To change that means changing both policies coming out of City Hall and current City Hall culture. Environmental Protection is a Do-It-Yourself proposition these days.

SHINGLE MOUNTAIN FUNDRAISER MAY 30th

Downwinders Wins Prestigious Ben and Jerry’s Foundation Grant to Help Build New DFW Air Quality Monitoring Network

Downwinders at Risk is excited to announce that we won a $20,000 Ben & Jerry’s Foundation grant to help add high-tech, low-cost air quality sensors to our growing community air network powered by the expertise and hardware of the University of Texas at Dallas.

While we applied in the past for these prestigious national grants, this is the first time we’ve received one. It’s kind of a big deal for us.

Our winning grant proposed combined old-fashioned community organizing with the installation and maintenance of new solar-powered, wifi-connected Particulate Matter monitors. Real time information from those monitors will be accessible through a free app you can download on your phone. This information can be used to propel a variety of public health and public policy initiatives.

Depending on how much of a bulk discount we can get, the grant should be able to buy at least 20-30 additional more monitors to add to the 11 we’ve already ordered. Our plan is have all of these up and operating by this time next year.

Dallas’ Joppa neighborhood will get the first wave of these. We’re already finding locations for them in the community. We’re beginning discussion with West Dallas community leaders to bring at least as many or more monitors to that abused part of town as well.

Residential communities adjacent to or directly downwind of major PM pollution sources are the first priority, but we hope to keep expanding to make the network as comprehensive as possible. There are plans to begin assembling a community air network board or committee of some type to oversee the Network. Stay tuned.

“Build-A-Better Bus Stop” Design Contest Winner To be Decided This Saturday

Better Bus Stop Design

Competition Finals

This Saturday May 4th

6 – 9 pm

Better Block Foundation HQ

700 West Davis

Look, Judge, Vote.

Downwinders at Risk is one of this year’s contest sponsors because it’s all about building a more people-friendly bus stop that’s also trying to minimize riders’ exposure to street level Particulate Matter pollution (PM.) Better Block was inspired to tackle this problem via its collaboration with Downwinders at Risk back in December on our Electric Glide Pub Crawl. This is a great example of how simply talking more about PM pollution can trigger a cascade of unintended beneficial effects.

Better Block gave 11 teams $250, four hours on their CNC router (basically, a giant printer for wood), and freedom to create whatever they want, as long as it’s a bus stop. Nine teams made 90 second videos on their designs you can see at the bottom of Better Block’s home page. They include a local couple, a Boston collective, Dallas’ own City Lab High School and UTA grads.

On Saturday those teams will actually build their prototypes at Better Block headquarters on West Davis. They’ll have judges determine a winner, but the public can also pick its favorite stop. Live Music and food trucks on site. Come and see the future while you wait for election returns.

Southern Sector Rising Went Eyeball to Eyeball with Dallas City Hall over Shingle Mountain. Dallas City Hall Blinked.

After a year of excuses, a determined group of women and their supporters shamed the City into finally taking action to close down the worst environmental health and justice crisis in Dallas.

When the collapse came, it came quickly.

Halfway through their Wednesday March 20th news conference giving authorities an ultimatum to shut down “Shingle Mountain” or face protests and possible civil disobedience, members of the freshly minted Southern Sector Rising Campaign for Environmental Justice learned the City of Dallas was reversing course and moving to close Blue Star’s year-old asphalt hell.

Only a week before, the official party line from City Hall was that the self-described “recycler” had all the permits it needed. Staff said critics’ description of Blue Star’s operation as an illegal dumping ground was wrong. It had “a right to be there.”

Now, on Wednesday….well, now circumstances had changed. The political circumstances that is.

Now there was a new coalition of frustrated Southern Dallas residents and Old School Icons like Peter Johnson, Luis Sepulveda and John Fullenwider staging an emotionally-charged news conference with chants of “Shame on Dallas” ringing loudly up and down the corridors of City Hall. Now there was a publicly-leaked report with incriminating evidence of official wrongdoing. Now there were swarms of cameras and reporters hanging on the every word of a middle-aged, middle-class, horse-loving DART employee who had been ignored for such a long time.

Three Generations of Dallas Environmental Justice Advocates: John Fullenwider, Luis Sepulveda and Marsha Jackson

Led by Marsha Jackson and her Choate Steet neighbors, Temeckia Durrough and Miriam Fields of the Joppa Freedman Town Association and Olinka Green from the Highland Hills Community Action Committee, with Stephanie Timko as media czarina, the Southern Sector Rising Campaign for Environmental Justice did more than just win a huge victory for an much-abused part of Dallas. It gave Southern Dallas residents a new model for effectively changing their circumstances.

An ad-hoc group that hadn’t even existed in February had the temerity to put City Hall on trial in its own lobby for Big D’s most spectacular municipal act of environmental racism in years. And it wasn’t even a fair fight.

An eye-opening state inspector’s report Downwinders sent to reporters a few days before the news conference officially documented permit violations and red flags too large to defend. Although Blue Star had promised the state in April 2018 it wouldn’t store more than 260 tons of waste at its site, it was already storing 60,000 tons in December. Blue Star was supposed to have a Fire Protection Plan. It didn’t. Blue Star was supposed to have adequate funds to close and clean up its site. It didn’t. Blue Star was supposed to randomly test incoming loads of shingles for asbestos. It didn’t.

This is how bad it was: Blue Star’s mocking of the law was too much even for Gregg Abbott’s Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Or the City of Dallas.

So long before the last speaker spoke in the Flag Room, news came that the City had pulled the Certificate of Occupancy for the largest of the two Blue Star tracts, something it had previously said wasn’t possible. Then it announced it was taking the company to court the next day to get an emergency Temporary Restraining Order to close Blue Star down.

That City staff could so shamelessly pull off such a dramatic flip flop over a matter of a few hours is testimony to both the fury fueling the Campaign, and the overwhelming evidence that Blue Star and its government enablers had allowed a full-blown illegal dump to grow… and grow…and grow. The only thing missing from the turnaround was an apology and acknowledgement to the women that had forced City Hall’s hand.

In Thursday’s hearing on the Restraining Order, the City of Dallas cited a number of missing municipal and state permits it now said Blue Star needed, including a Special Use Permit, an air quality permit, and a permit for storage in the flood plain – none of which the City had demanded when Blue Star had opened for business a year earlier. Despite the lack of these permits the City was now saying were essential, it had kept telling reporters, Council Members, and residents alike that Blue Star was a legal business right up until the time of the news conference.

It wasn’t. Ever. But it took a group of frustrated Southern Dallas residents to expose that lie.

Of course in the hearing itself the heretofore lack of official city concern about these lacking permits was perturbing in the extreme for the attorney representing Blue Star, who said City Hall had already signed-off on its operations.

Of course in the hearing itself the heretofore lack of official city concern about these lacking permits was perturbing in the extreme for the attorney representing Blue Star, who said City Hall had already signed-off on its operations.

“The City told my client there were NO air quality problems,“ he protested to the judge. That was undoubtedly a true statement. But that conclusion was rendered before a brigade of angry residents showed up at City Hall demanding Dallas enforce the law.

Now, presto-chango, the City was emerging out of its dilapidated telephone booth with its moldy Toxic Avenger costume on and finding plenty of air quality problems, albeit in a anecdotal, non-quantifiable, way.

Because despite being “very concerned” about air pollution from Blue Star, the City of Dallas never monitored air quality from the facility before it got to court. Neither did the state. Only Downwinders at Risk, plugging-in one of our own portable PM monitors on the top of Marsha Jackson’s window unit for days at a time, captured any credible scientific evidence of air pollution harms.

Those results were released at the March 20th news conference and showed levels of Particulate Matter pollution that UNT’s Dr. Tate Barrett concluded “poses a significant health risk to the residents.”

But in court, the City didn’t even mention those EPA-calibrated results.

For the first time in memory it was the regulators using only their senses to call for a crackdown – what they saw and heard and smelled at Blue Star’s site – and citizens showing up with Real Science.

Lacking any monitoring data of their own, Dallas city attorneys sounded like countless over-matched and overwhelmed residents from past TCEQ hearings, pleading with the judge to accept their word that the air pollution was so darn obvious…if not directly quantifiable because, well, no, we didn’t actually do any monitoring. We don’t know how to do that.

A layer of asphalt dust coated a Downwinders air quality monitor while it was recording levels of PM pollution at Marsha Jackson’s house in early March

This lack of any data to back up its air pollution claims was one of the most embarrassing parts of the hearing for the City. One wonders when James McQuire and his Office Of Environmental Quality & (Rockefeller) Sustainability’s stubborn refusal to buy its own air monitors will eventually cost the City (and its residents) in court.

But every time the City’s case looked in trouble, Blue Star’s attorney dug a deeper hole. He wanted the judge to know “shingles make really good fill” and that the spring-fed creek that ran through the company’s site was merely “a drainage ditch” and asking, after all judge, what is the true and right definition of “combustible” under Texas law?

Judge: “It means catch fire.”

Everyone but the Blue Star attorney chuckled.

After 45 minutes, Judge Gina Slaughter had heard enough and ruled in favor of the Restraining order. It took effect March 22nd and runs until Midnight on April 3rd.

Before that happens, an 11 am Wednesday morning hearing will be held in the same courtroom to decide whether to extend the Temporary Order into a more permanent one. Word is that Blue Star was caught doing business during the last week when it wasn’t supposed to be on site at all. If true, it seems unlikely Blue Star will be granted a reprieve, despite the optimism displayed on the company’s website. “We fully expect to be open on Thursday April 4th, 2019″ it proclaims.

Before that happens, an 11 am Wednesday morning hearing will be held in the same courtroom to decide whether to extend the Temporary Order into a more permanent one. Word is that Blue Star was caught doing business during the last week when it wasn’t supposed to be on site at all. If true, it seems unlikely Blue Star will be granted a reprieve, despite the optimism displayed on the company’s website. “We fully expect to be open on Thursday April 4th, 2019″ it proclaims.

Not if Marsha Jackson, her friends in the Southern Sector Rising Campaign, and now their reluctant ally, The City of Dallas, get their way.