Citizen Action

The Mansfield Fight Goes National And Industry Gets Worried

We must be doing something right.

We must be doing something right.

Last Thursday, Energy in Depth, the national PR arm of the oil and gas industry, singled out Downwinders at Risk for our support of longer setbacks between people and gas industry facilities in Mansfield and other North Texas cities.

EID calls these setbacks, now passed in DISH, Denton, Southlake and Dallas, "defacto bans" because they require wells and compressors to be anywhere from 1000 to 1500 feet from homes, schools, park and other "protected uses" – to use city zoning lingo.

But of course these setbacks are defacto bans only because industry wants them to be – not because there are any technical obstacles to them reaching the gas underneath these cities due to distance. Gas operators can now punch a hole and reach deposits up to at least a mile or two away from where they place their rig on the surface. That's more than three 1500-foot setbacks end-to end. Operators have to spend more to drill to get that gas, but that's the price they pay for trying to place heavy industry in the middle of residential areas, parks, or near schools – something most cities don't allow when it comes to hazardous waste incinerators, chemical plants or landfills. Part of the problem is the inherent arrogance of the gas industry's position – it wants to pollute like a heavy industry, but it doesn't want to be regulated like one.

You know the folks in Corporate are getting worried when these things pop up on the Energy in Depth agenda. They understand their much-beloved "Fort Worth model" of less protective 600-foot setbacks and looser regulations in now under organized assault. While the rest of us see a constant barrage of new studies coming out every month emphasizing the dangers to human health of proximity to gas facilities, the industry wants time to stop in 2010, before we knew so much. But time marches on. And so does knowledge, and then public opinion.

Mansfield is deep into the Shale. It shares a border with Ft. Worth, unofficial headquarters for the Barnett Shale Energy in Depth crowd. A rejection of Cowtown's approach to regulating the gas industry here would be a major setback to the industry. The stakes are high. Just in the last week, two national publications, a subscription-only national newsletter called Environment and Energy Daily, and the Center for Public Integrity, have posted stories on the Mansfield fight. They've hit a nerve. That's why Energy in Depth is writing about it.

Getting criticized by EID is recognition that the partnership between Mansfield Gas Well Awareness and Downwinders at Risk is having an impact. We consider is a badge of honor. Our only regret is that it came too late to be used in our traditional end-of-year fundraising letter. Because after months of frustration, Mansfield residents are finally getting the attention they and their complaints deserve from their city council and the media. It's a national fracking fight hotspot. That's not an accident. That's good organizing.

Building Momentum in Mansfield

Good things come in threes. Lance Irwin, Erick Orsak, and Tamera Bounds proved that again on Wednesday night when they led the Mansfield Gas Well Awareness contingent during the Mansfield City Council's "work session" on rewriting the city's gas drilling ordinance.

Good things come in threes. Lance Irwin, Erick Orsak, and Tamera Bounds proved that again on Wednesday night when they led the Mansfield Gas Well Awareness contingent during the Mansfield City Council's "work session" on rewriting the city's gas drilling ordinance.

Combined, they projected just the right mix of competence, skepticism, and experience to combat the "Don't worry, be happy" approach of the Railroad Commission and Texas Commission on Environmental Quality presentations that preceded them in the agenda.

(By the way did you know, that according to Austin, the average response time of a TCEQ inspector responding to a complaint was only 5 hours? Downwinders at Risk is willing to pay $100 to the charity of the inspectors' choice if anyone out there has ever gotten a response that quickly. After almost 30 years of dealing with state environmental agencies, we can't recall a single instance where it took less than a day for an inspector to show up, even when the situation was "urgent.")

By putting the three residents in the same horseshoe as industry, state agencies, and itself, the Council elevated the status of the resident's group beyond anything it had enjoyed in previous rounds of jousting over drilling. Whether that leads to the kinds of substantial changes to the city's drilling ordinance the group is pursuing remains to be seen.

What was obvious after the formal presentations ended and a more informal question and answer period followed was the large disparity in monitoring and self-regulation within the industry. There were at least 10 or 12 gas operators sitting at the table during the event. Conspicuous by its absence was Eagleridge, the source of many complaints in Mansfield and of course, the company that ignited the Denton fracking vote controversy.

But Eagleridge's Chief Operating Officer Mark Grawe was present, in the back of the room, trying to keep a low profile. It didn't work. Let's just say when you get called on the carpet by Stephen Lindsey, the Mansfield Council member whose day job is the "Government Relations and Community Affairs Director" for gas industry giant Quicksilver, you know you're not going to have a good night. As the evening wore on, it was clear Eagleridge was being portrayed as the poor, white trash cousin of the more established players like XTO and Chesapeake. The company lacked the remote sensors, automatic cut-offs, and other kinds of precautions that the rest of the industry reps liked to brag about. By the end of a rigorous cross-examination of Grawe by the residents' group, there was an unacknowledged consensus that perhaps the floor for regulating existing wells needed to be raised in Mansfield so that moving target known as "industry best practices" was updated applied to all.

More ambiguous was the response to the residents' request for a 1500-foot setback to replace the current 600 feet requirement – with a variance that can decreases that distance to 300 feet. Some industry representatives and council members want to frame the problem in terms of incidents and accidents that can be fixed with better equipment, rather than systematic changes that require separating people from heavy industrial activity, no matter how good the intentions are.

Also left hanging was how to better regulate polluting compressors. The city's lawyers, who've written protective ordinances for Dish and Southlake, was more circumscribed with their Mansfield employers. Cities can't regulate pipelines and mid-stream compressors for "safety standards," already addressed by the Railroad Commission they said. Left unsaid was that cities can and have regulated compressors for noise and "odors," otherwise known as toxic chemical exposures.

Bounds presented the city council with what she called a model ordinance that combined the best, most protective aspects of drilling regulations from DISH, Southlake, Dallas, Denton, Arlington and even Fort Worth. Saying these were legal requirements that hadn't been challenged by industry and so were available for adoption by the city, Bounds put the council on the spot by saying Mansfield needed to protect its citizens at least as much as these other municipalities and had no legal excuse for not doing so. Mayor David Cook took note of the work she'd done in compiling the new ordinance and said the city would perform its own side-by-side comparison and come back in January to continue the discussion.

Overall, the mood of the evening was cautious but positive. It was hard not to be impressed by the residents' knowledge and expertise, and everyone was civil in public. Afterwards, however, one of the first things Bounds heard was an industry operator telling her there was no way he was going to accept a 1500-foot setback. There is still plenty of work to be done. But it was a step in the right direction. And there are no big changes without incremental changes first.

It helped that the media were out in force, trying to identify the next fracking hotspot after Denton. There was a row of TV cameras and local and national print reporters showed up to take notes. Channel 8 had the best coverage of the evening, and if you can get past the paywall, here's the Star-Telegram's take.

As has been noted before, Mansfield is no Denton. It's not even Southlake or Flower Mound. It resembles Ft. Worth more than it does Dallas in terms of politics and attitudes toward the gas industry by the Powers That Be. It has more wells per capita than just about any place else in the Shale. But those are all reasons that make it worth fighting the good fight there. If residents can make their case effectively and change their situation in Mansfield, then there really is hope for everyplace else in the Barnett. Stay tuned.

Make Your Butt A Force for Good Tonight

Woody Allen is famously credited with the line that "showing-up is 80% of life." With organizing, it's more like 90%. There are at least two places to be tonight where just your butt in a seat will make a huge, positive difference:

Woody Allen is famously credited with the line that "showing-up is 80% of life." With organizing, it's more like 90%. There are at least two places to be tonight where just your butt in a seat will make a huge, positive difference:

1) Mansfield City Council Work Session on a New Gas Drilling Ordinance, 6 pm, Mansfield Performing Arts Center Workroom, 1110 West Debbie Lane, (near Hwy 287 – just south of I-20) (map).

After almost a year of struggle, residents of Mansfield are getting a hearing tonight in front of their city council. Unfortunately, the council, including two members who make a living from the gas industry, are making the the residents take on the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the Texas Railroad Commission, 10-13 gas industry representatives, pro-industry state representatives, senators, and Congressman, as well as their own city staff – all in one evening. They're besieged, and they really need your help tonight.

We have it on good authority that the Mansfield Mayor is using this set-up to "gauge public opinion on the issue" even though members of the public won't get to speak. So it's all about attendance – butts in seats.

Mansfield isn't Dallas. It isn't Denton. It's not even Southlake or Flower Mound. It's deeper into the Shale, more blue collar, and more pro-industry than any other city that's been challenged over their old drilling ordinance in the last several years. The city has more gas wells now per capita – over 200 in a city of 60,000 – than just about any other place in North Texas – with a potential for 300 more. Concerned residents are at a disadvantage in trying to change the status quo.

Just your being there in a seat tonight sends a message you care about this issue. And if you live in Tarrant county or any place else where there's gas drilling in the Metromess, it's in your own self interest to help them in Mansfield. A victory there will make it more possible to win in other places. It will mean less air pollution from their wells and compressors blowing downwind. It will mean the tide is moving further west.

So do yourself, the region, and the cause a favor and show up tonight. You don't even have to speak. You just have to be present to win.

2) Trinity Toll Road Debate – 6:30 p.m. at Rosemont Elementary School, 1919 Stevens Forest Drive (map)

State Representative Rafael Anchia is sponsoring this debate over this leftover 20th Century boondoggle that features almost all the major players on both sides of the issues – Michael Morris, Mary Suhm, Patrick Kennedy and Scott Griggs. Again, your presence sends a valuable signal – that you're opposed to this floodplain toll way, and that this will be an important issue in the May Dallas elections. Go and be active members of the peanut gallery – cheer on the opponents, jeer the supporters.

It's particularly important that the public show increased interest tonight as Suhm and Mayor Rawlings conspire to muddy the waters with a new "review" of the plans of the road. They hope to give Citizen Council-backed candidates in the May election a way out of a simpey yes or no answer to the Toll Road – by saying their waiting for the review. You need to make sure they get the message that nobody is falling for that ruse.

Your butt can be a powerful voice for change tonight, or it can sit on the couch. Get out and show-up.

“I’m on Both Sides of It.” Mansfield City Councilman Stephen Lindsey Has the Worst Conflict of Interest in the Barnett Shale

Stephen Linsdey is an entrenched member of the oil and gas industry. In the mid-Oughts he worked for Flowserv, the multinational manufacturer of valves and pumps used at thousands of oil and gas facilities worldwide. From 2007 to 2008 he was put in charge of protecting and developing Iraqi oil fields during the Iraq War. Beginning in 2008, just as the local Shale boom was taking off, he went to work for Quicksilver Resources inc, the sixth largest producer in the Fort Worth Basin, where he's been ever since, serving as Senior Director Of Government Relations and Community Affairs.

Stephen Linsdey is an entrenched member of the oil and gas industry. In the mid-Oughts he worked for Flowserv, the multinational manufacturer of valves and pumps used at thousands of oil and gas facilities worldwide. From 2007 to 2008 he was put in charge of protecting and developing Iraqi oil fields during the Iraq War. Beginning in 2008, just as the local Shale boom was taking off, he went to work for Quicksilver Resources inc, the sixth largest producer in the Fort Worth Basin, where he's been ever since, serving as Senior Director Of Government Relations and Community Affairs.

According to the company's job description, Lindsey's responsibilities "include community relations, municipal/city engagement, governmental/legislative affairs, regulatory/permitting, external affairs and corporate/public relations." He's also Treasurer of Quicksilver's Political Action Committee, overseeing the distribution of thousands of campaign contributions to officials such as Arlington Mayor Robert Cluck, Fort Worth Mayor Betsy Price, Railroad Commissioner Barry Smitherman, and Texas House Representative Jim Keffer, Chair of the House Energy Committee.

Lindsey's job is to smooth over any regulatory obstacles in the way of Quicksilver's production goals. He's the company's lead negotiator with local and state governments. He also is in great demand on the oil and gas industry speaker circuit as an expert on how to deal with what he says are those "working against industry's interest."

In his own words, "My role in my organization is to make insure the guys that want to drill wells and complete wells, and run pipelines, and put in surface equipment, and move trucks can do it uninhibited. Can do it without fear their permits are gonna get denied, or the regulatory structure is going to come down on them."

That's his day job. But Stephen Lindsey is also a Mansfield City Council member. In fact, as coincidence would have it, he's the city council member the Mayor has put in charge of overseeing the city's gas drilling policies.

And now, he's the city's go-to guy for the re-examination of Mansfield's obsolete 2008 gas drilling ordinance that's been the subject of a steady grassroots campaign of determined residents. You got a problem with that?

As it turns out, Lindsey isn't even the only member of the Mansfield city council who's intimately connected to the oil and gas industry. Larry Broseh is president of a drilling parts manufacturer whose clients include gas patch operators all over the state, including the Barnett Shale. That's two out of the seven city council members who have a pretty big conflict of interest.

But it's not just who Lindsey works for that makes for the outrageous double duty. It's what he does for Quicksilver. He's the slick PR guy that interfaces with local city councils to downplay the hazards of fracking in order to win permits. He's the spokesperson in the media. If Quicksilver had wells in Mansfield (the closest ones are in Arlington), the council would be sitting across the table from Stephan Lindsey. And as a national poster boy for fracking's public relations strategies, he's often the friendly face of the industry across the country. He's certainly fracking's most high profile elected official in the Barnett. And he wants you to know he's sincere about trying to get "the best product" i.e the best conciliatory agreements between industry and government.

With only 60,000 residents, but over 200 wells and another 300 potential ones to come, Mansfield has twice as many wells per capita than Denton and almost a third more per capita than even Fort Worth. Residents there are pressing to replace an industry-blessed "Fort Worth model" 600-foot setback (that's really a 300 setback with variances) with a "Southlake/Dallas model" 1500-foot setback minus any variances. Outside of Denton, now in court over an outright ban on fracking, Mansfield is the next battleground in the Barnett Shale for the clash between these two competing regulatory templates.

Lindsey is well aware of this clash. Part of his job is going around the country warning industry about the growing power of local governments in regulating drilling. He cites Flower Mound and Denton as bad examples. As one industry conference panel moderator posed it to Lindsey, "What's your advice on how to prevent a Denton?"

According to Lindsey, "local governments are increasingly at odds with state government." Cities don't feel as if they're protected by state entities like the Railroad Commission or TCEQ anymore. "Detrimental regulations" by municipal governments are on the rise. When older white Republicans are opposed to you, "that's a sea change."

Much to Lindsey's chagrin, unlike Colorado, where the Attorney General has taken local county governments to court because of this overreach, Texas home rule cities "can do whatever they want." If the cities think it's in their best interests, those regs "are going to stand" unless they're challenged. You can almost taste the anticipation he has over the lawsuits the Denton fracking vote has generated as a chance to settle the score and cut the cities down to size.

In his presentations to industry peers, Lindsey boosts about his role as a Mansfield city council member. "I'm on both sides of it. I'm out lobbying, er, presenting at City of Fort Worth, City of Arlington, City of Haslet, City of Southlake, City of Northlake – all of our operational areas, trying to get our permits approved and on the other hand, I'm sitting on our own city council listening as XTO, and Chesapeake, and other operators come in and present there."

Traditionally, the strictest interpretations of conflict of interest have meant that the elected official or a close relative had to have worked for or owned stock or or percentage in the specific company being discussed. Since Quicksilver doesn't have any wells in Mansfield, Lindsey passes that test. But in terms of a more general conflict over the escalation of local regulation of the gas industry, his positon in Quicksilver and as an industry spokesperson certainly does pose a conflict.

He doesn't hesitate to describe threats to the industry as a whole, or to advise other companies on how to "manage them." No matter how much more protective to public health it might be, wouldn't the spread of a Dallas-like model of "detrimental" regulation of drilling to a place like Mansfield be a bad precedent for the industry as a whole? Wouldn't it constitute a threat to other operators like Quicksilver, whose own future wells might be targeted next in Arlington, or Haslet, or God forbid, even Fort Worth?

If he was being honest, Stephen Lindsey the industry lobbyist would have to say yes. After all, as he noted to a Colorado reporter in an article over a local County's demand for a monitoring water well Quicksilver didn't want to install, "We’ve got to make prudent decisions about what option is best for the company."

In 2010, the City of Fort Worth Ethics Committee ruled that three gas company employees had a conflict of interest in serving on its air quality study committee by concluding, "The level of their loyalty to their employers has put them in a position of wearing two hats."

The same is true of Stephen Lindsey. Mansfield residents shouldn't have to guess which hat Lindsey is wearing when he's working as a city council member, or whether he's putting their well-being or the industry's bottom line first.

(Most of the quotes used in this post come from a presentation for the American Business Confernce in October, avaialble for viewing online: http://vimeopro.com/lbcg/fe14/video/108496562)

2014 DFW Smog Report: Good News But Don’t Hang Up the Gas Mask Yet

For the first time since DFW began recording its smog levels, the region's three-year running average dipped below the 1997 eight-hour 85 parts per billion (ppb) standard. After years of leveling off at around 86-87, it's dropped to 81 ppb. That's good news.

For the first time since DFW began recording its smog levels, the region's three-year running average dipped below the 1997 eight-hour 85 parts per billion (ppb) standard. After years of leveling off at around 86-87, it's dropped to 81 ppb. That's good news.

DFW's decrease is attributed to 2011's terrible numbers rolling off the board and a wetter, cooler and windier summer than normal these last five months or so. As both drought-ridden 2011 and this year's results demonstrate, weather still plays an extremely critical role in how large or small our smog problem will be. Another summer or two like 2011 could easily put us back over the 1997 standard. More wet and cooler weather could see the decrease continue.

The news would be better except that we were supposed to have originally accomplished this milestone in 2009, then again last year after a second try, according to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

As it is, we still haven't reached the current, more protective 2008 national standard that was revised downward to 75 ppb after a review of the scientific literature.

In January, TCEQ will host a public hearing on its proposed "plan" to EPA to meet that goal that predicts most, but not all DFW monitors will reach 75 ppb by the summer of 2018.

Despite overwhelming evidence that new controls on the Midlothian cement plants and the reduction of gas industry pollution could speed this achievement, TCEQ's new plan contains no new pollution control measures on any major sources of smog polluters – cement kilns, coal plants, gas sources – but instead relies on the federal adoption of a new lower-sulfur gasoline mix for on-road vehicles. Like past proposals by Rick Perry's TCEQ, this one depends solely on the feds to get them into compliance. TCEQ isn't lifting a regulatory finger to help.

And its new plan once again aims high, not low. At last count, there were at least three Tarrant and Denton County monitors that TCEQ admitted would still be above the 75 ppb standard at the end of 2018. "Close enough" is the reply from Austin.

From a public health perspective, it's even worse. Why does the ozone standard keep routinely going down? Because new and better evidence keeps accumulating to show widespread health problems at levels of exposure to smog that were once considered "safe." About every five years, the EPA's scientific advisory committee must assess the evidence and decide if a new standard needs to be enforced to protect public health.

For most of the last ten years, the position of this independent panel of scientists is that the standard should be somewhere between 60 and 70 ppb. They were ignored in 2008. They were ignored in 2011. They once again came to this conclusion last May. What was the evidence that persuaded them? That the current 75 ppb standard for smog causes almost 20% of children in "non-attainment areas" to have asthma attacks, and leads to hundreds of thousands of deaths every year. Cutting the standard to 60 ppb reduces those deaths by 95%. Since the Clean Air Act states the EPA is duty bound to set a smog standard protective of human health, 60 ppb seems to be the threshold level that the current scientific literature says is actually safe for the majority of the population most vulnerable to the impact of bad air. By contrast, a smog level of 70 ppb only reduces those deaths by 50%. (Policy Assessment for the Review of the Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standard, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air and Radiation, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Health and Environmental Impacts Division, Ambient Standards Group, August 2014)

By December 1st, EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy must decide whether to officially recommend a standard in that 60-70 ppb range. It looks as though this time, the EPA might just endorse what the scientists are recommending, although it's unclear whether it'll be the upper or lower part of that range.

So even while the TCEQ is saying it's "close enough" to achieving the 75 ppb standard left over from George W's administration by 2018, the evidence is that level is too high to prevent large public health harms and must be lowered. A lot.

This is why it's so infuriating that the TCEQ is satisfied with getting only "close enough" to a 2008 standard that's about to become obsolete. Austin knows it could demand better air pollution control measures on the market right now that would accelerate the decrease in smog. It knows the pubic health would benefit from requiring such measures. But it's willing to condemn DFW children and others at risk for many more years for the sake of keeping its "business-friendly" reputation.

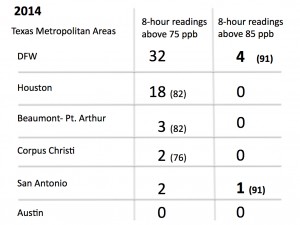

And while this year's slip below the 85 ppb standard is a sign of some progress, it remains true that DFW still has the worst air in Texas – a title we took from Houston years ago. Take a look at the chart summarizing the 2014 ozone season across Texas. Despite the nicer weather, DFW still had almost twice as many readings above 75 ppb as Houston and four above the 85 ppb standard. Houston had no readings above 85. In fact, San Antonio was the only other city to record a level so high – once.

DFW still has a smog problem and all it takes is another hot and dry summer to see it escalate. We need the help more controls on major sources could give us. We need Selective Catalytic Reduction on ALL the Midlothian cement and East Texas coal plants. We need electrification of gas compressors in the Barnett Shale. This should be the message to both the TCEQ and EPA during the public hearing in January.

DFW still has a smog problem and all it takes is another hot and dry summer to see it escalate. We need the help more controls on major sources could give us. We need Selective Catalytic Reduction on ALL the Midlothian cement and East Texas coal plants. We need electrification of gas compressors in the Barnett Shale. This should be the message to both the TCEQ and EPA during the public hearing in January.

DFW smog in 2014: we've met the Clinton era standard for now, on the way to trying to get "close enough" to the W Standard, and still very far from a new Obama standard. Don't hang up the gas mask yet.

After a 14-year Campaign, State-of-the-Art Pollution Control Finally Coming to Midlothian

(Midlothian) After a 14-year effort by local citizens, Holcim US Inc. is applying for a permit to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to install a Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) unit in their Midlothian facility. It's the first application for commercial use of SCR technology in any U.S. cement kiln.

(Midlothian) After a 14-year effort by local citizens, Holcim US Inc. is applying for a permit to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to install a Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) unit in their Midlothian facility. It's the first application for commercial use of SCR technology in any U.S. cement kiln.

DFW-based clean air group Downwinders at Risk has been advocating the use of SCR in the three Midlothian cement plants located just south of I-20 since 2000, when a German cement kiln first operated the technology successfully.

Together, the TXI, Ash Grove, and Holcim plants represent the largest concentration of cement manufacturing in the country and are a major contributor to DFW's historic smog problem.

"We need this pollution control technology in North Texas, and we're pleased to see Holcim's application," said Downwinders Director Jim Schermbeck. "But we wish residents could enjoy its results sooner than Holcim intends."

The SCR unit is planned for Holcim's idle Kiln #2 while a more common Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer will be built for its operating Kiln #1. Both technologies are being installed to meet new EPA emission standards for hydrocarbon pollution from cement plants. Those standards themselves were championed by Downwinders and other citizen groups in 2009, with over 200 people showing up at an EPA hearing the the DFW Airport Hotel to support them.

The deadline for compliance with the new standards is September 2016. However, restarting of Kiln #2, and the introduction of SCR in Midlothian, is dependent on local demand for Holcim's cement, which is still recovering from weak demand during the recession. That lack of demand could delay the technology's inauguration until after 2016.

Nevertheless, according to Schermbeck, Holcim's application for a permit to install SCR makes it's more likely that all of the Midlothian cement plants, and others in EPA "non-attainment areas" for smog pollution around the country, will be adopting it sooner rather than later.

"Holcim's application sets a precedent that's hard to ignore by regulators in Austin and Washington. For the first time a US cement plant has expressed enough confidence in SCR to make it a technically and economically-viable choice for pollution control. There's no going back."

SCR is widely considered to be the most advanced form of pollution control for cement manufacturing, capable of reducing smog-forming pollution by 90% or more, along with significant reductions in Particulate Matter, metals, and Dioxins.

Although about half a dozen European cement kilns are successfully operating the technology, U.S. plants have refused to endorse it. Two EPA-sponsored pilot tests of SCR are being conducted at Indiana and Illinois cement kilns as part of court-ordered settlements. Holcim's application for its Midlothian kiln is the first time and American cement plant is voluntarily approving SCR use.

Although it's not coming in time to impact the current DFW clean air plan, due to go to public hearing in January of next year, Holcim's application will put SCR on the agenda for the next such plan.

Just two weeks ago, EPA staff recommended a new ozone, or smog, standard of between 60 and 70 parts per billion over an eight hour period versus the current limit of 75 ppb. Adoption of a stricter standard is expected to occur by late next year, meaning a plan to meet that standard will be gearing up sometime in the next three to five years. By that time, Holcim's SCR unit should have a track record that can be cited as a reason for all the Midlothian cement plants to use it.

Schermbeck noted that just last month representatives of the TCEQ told a regional air quality meeting in Arlington that SCR was neither an economical nor technically feasible pollution control option for the Midlothian cement plants. He said Holcim's application belies that claim.

A public meeting on the Holcim permit application is being scheduled for early November.

Arrival of SCR on the scene marks the latest and the most dramatic milestone in the transformation of the local cement industry since Downwinders at Risk was founded 20 years ago to stop the burning of hazardous wastes in the Midlothian kilns.

After a 14-year battle, TXI halted its hazardous waste-burning operations in 2008. Downwinders then pursued a six-year "green cement" campaign to replace all seven obsolete and dirtier wet kilns with newer "dry kiln" technology. That campaign ended in 2012 with the announcement that Ash Grove would shutter its three wet kilns and build a new dry kiln in their place. That plant is due to go on line this year.

Adoption of SCR remained a goal of the group through four different DFW clean air plans going all the way back to 2000. Schermbeck said his group made incremental progress each time, winning small and large battles that directly lead to today's news.

"Holcim's application for SCR is the latest testament to the persistence and focus of a small group of committed citizens who have pulled and pushed the U.S. cement industry into the 21st Century one step at a time."

Labor Day 2014: Why Texas Environmentalists Should Be Pro-Union

There's one population of victims of industrial pollution that often has it even worse than those who live downwind: those that work within.

There's one population of victims of industrial pollution that often has it even worse than those who live downwind: those that work within.

Groups like ours make it their business to represent the interests of "frontline" residents who live adjacent to, or in close proximity of, places that routinely release crap in the air that affects their health and well-being. Collective action is promoted as a way to address that situation and, in our experience, it works more often than not. At its essence then, Downwinders is a kind of union of pollution victims.

Local residents who decide to step out of line and speak out against the facility's pollution are often ridiculed, threatened, and ostracized. Especially in small towns where the facility is among the largest employers or taxpayers. Because of the interconnections and economic ripple effect of such facilities, some activists get warned about losing their jobs even though they may not work for the offending company itself.

Imagine then the pressure on workers inside the facility whose very livelihood rests on their silent consent. Despite a constant stream of studies showing exposure levels for employees of polluters at many times the levels of those outside company property, they have no collective means to help them relieve their condition. Except for unions. Which means in Texas, they usually don't have any recourse at all.

Lack of union representation for these workers not only diminishes their job security, it means they're much less likely to be willing or able to help those outside the fence line who are also being shat-on. They're on their own, with no organizational backing. They have no access to collective action. In many ways they're less powerful and have fewer options than those getting doused in their own homes across the street from the company. Sometimes they ARE the people in those homes and get it coming and going.

When there's no union, there's much less chance of any kind of meaningful dialog between activists and workers, even though they may share the same concerns and be affected by the same pollution. There's one less ally for activists to recruit in seeking more effective pollution controls or cleaning-up a site. The flow of information about what's really going on inside the facility is circumscribed. Industrial polluters stand a better chance of holding out against change if they can keep those on either side of the fence line from joining forces.

On the other hand, some of the most effective pollution control measures among Texas Gulf Coast refineries and chemical plants are the result of strong unions with the ability to collectively bargain for change. In countries with a longer and stronger union movement, it's the "Labor Party" that usually voices the loudest support for environmental progress.

Unions aren't perfect. They can become as bloated and neglectful as any corporation. They can stifle progress by parroting the wrong-headed notion that less pollution means less jobs. But they're the only counterweight to corporate power within the facility because they can affect the bottom line with a slow down or strike – more potential power than activists often have after years of organizing. If you're an environmental activist, it's in your own self-interest to promote unions.

Likewise, if you're a union representing workers who are getting poisoned, it's in your own self interests to put pressure on the company or industry to clean-up its act by working with environmentalists who can exert their own kind of pressure for action.

That recognition of mutual self-interest is the driving force behind such efforts at the Blue-Green Alliance that merges unions like the Steelworkers, UAW, CWA, and SEIU with the Sierra Club, Natural Resources Defense Council, and, appropriately enough, the Union of Concerned Scientists, into a broader coalition working for climate change action. By working together, they can anticipate and head-off the sudden jerks of unemployment that would happen as we transition off of fossil fuels to a greener economy.

Imagine how much fertile ground could be plowed in discussions between the grunts at drilling sites and the people who live next door if there was a union of such workers that was as concerned about the health of their members as residents were about the health of their children.

There's a long proud history of unions lending their power to social causes beyond the factory gates. Many were important in bringing the civil rights movement out of the South and making it a nationwide litmus test for elected officials. But that was when there was still a strong labor movement in the US; when the president of the UAW or Mineworkers Union were regular White House visitors, no matter which party was in power.

In Texas, a "right to work" state, unions often have the stigma of Leper colonies. They're used as political fodder for Republican candidates swearing they're the first step toward socialism, while being held as arm's length by Democrats for fear of being tainted with a "pro-union" label. Texas environmentalists are in a position to demand better.

Thirty years ago the observation was made that a conservative was just a liberal who'd been mugged. These days in Texas, thanks to fracking, an environmentalist is often as not a conservative who's been gassed. Many of those most affected by the oil and gas industry in North Texas and elsewhere are "dittohead" true believers, but also feel portrayed by officials who have traded their conservative credentials for campaign donations.

After a certain amount of abuse it's not hard for these right wingers to realize that they must organize themselves into collective action on behalf of their communities if they want to keep from being completely run over by companies that don't give a damn. Is it really that far a leap in logic to believe the same principle is true for workers who feel just as disposable to the same company?

Those that come to environmentalism through their own liberal values must reach out and make unions a part of the natural landscape. Just as Greens need to adapt by becoming more racially and economically diverse, so we must become more insistent that unions are an integral part of the change we're seeking. They can make our job a lot easier.

TCEQ: Link Between Fracking and Air Quality, No Cement Controls Just “Because”: Highlights From Tuesday’s Air Meeting

Dallas Resident Liz Alexander showed up at the Council of Governments meeting room on Tuesday to lend her support to the effort to get more out of an anemic state ant-smog plan than the state wants to give. She was a warm body whose presence would be its own statement of concern. She was being a good trooper by just showing up.

Dallas Resident Liz Alexander showed up at the Council of Governments meeting room on Tuesday to lend her support to the effort to get more out of an anemic state ant-smog plan than the state wants to give. She was a warm body whose presence would be its own statement of concern. She was being a good trooper by just showing up.

At first she sat far from the action amidst the rows of seats for bystanders and, despite encouragement, was resigned to just listening, because as she explained, "she didn't know enough to ask questions."

Then someone urged her to move up to the rectangle of tables where the presenters stand and deliver, where there are microphones to raise the volume of concerns and questions that might be posed by mind-numbing reassurances that everything is going hunky-dory. As more of these air quality meetings have occurred, citizens have been less and less shy about taking up these front row seats that look more official than the rest; look like they should be reserved for guys in suits. Increasingly they're occupied by people in street clothes.

And then, after much information had been paraded in front of Liz, she did something she did not think she was qualified to do only about 90 minutes earlier. She asked a question. It was about what assumptions had been included in the information about unspent air pollution clean-up dollars that are piling up in Austin. She got an answer from a local COG staff person in real time that satisfied her. In the space of one meeting she moved from spectator to participant.

And she wasn't the only one. More than any other meeting so far, this one involved more citizens asking more questions about more subjects – and it revealed just how thin the state's rationale is for doing nothing.

As predicted, it was a day for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to explain why its new DFW anti-smog plan was really going to work this time – unlike the five previous failures – and why it wasn't going to be considering any new controls on the Midlothian cement plants or on gas compressors – a refutation of the case Downwinders at Risk had made in its June 16th presentation.

But here's what really happened: For the first time in these proceedings the state admitted that oil and gas emissions have a big influence on regional air quality. And when a former County Judge asked an TCEQ's Air Quality Manager specifically why anti-smog controls already being used on cement kilns in Europe were not being considered for the Midlothian kilns, the staffer couldn't say, offering up only the longest, most pregnant pause by any state staffer in the history of these meetings.

After being heavily criticized for months for leaving at least four monitors above the 75 ppb federal smog standard even after its plan had ended in 2018, the state came back to this meeting saying they only had three sites above 75 ppb now, and by margins that didn't exceed the standard by more than 1 part per billion. Between June and August, there had been a remarkable drop in future estimated smog levels at the area's monitoring sties in the state's computer modeling – particularly at the historically most stubborn monitoring sites in Denton and Northwest Tarrant County.

What had caused this drop? A relatively modest decrease in Nitrogen Oxide pollution of around seven tons a day and a decrease in Volatile Organic Compounds of about 15 tons per day. That's not a lot of pollution to produce such a large decrease in monitor readings in the computer model.

A more important question is: where did the decreases in air pollution come from that could produce such dramatic results in the modeling? The answer: primarily from oil and gas industry sources. Based on TCEQ's own formula relying on the declining number of new wells being drilled in the Barnett Shale.

For the moment forget the methodological qualms you might have about that declining well assumption. Instead, appreciate the fact that the same state agency that couldn't bring itself to ever say the Barnett Shale was producing air pollution holding DFW back from meeting Clean Air Act smog standards now says that it's decreases in that very kind of pollution that are having such a substantial effect on the monitors in the western part of the Metromess that have been the most resistant to other control strategies. TCEQ has just proven a causal link its been denying for over seven years now.

It can't be just a one-way street. If declining oil and gas air pollution equals better air quality in the TCEQ's computer model, so increases in oil and gas pollution must lead to worse air quality.

There are all kinds of reasons to doubt that the drop in total oil and gas air pollution will happen at all or drop as fast or as sharply as the TCEQ predicts. Afterall, they're 0 for 5 in such matters. They may be underestimating the amount of total air pollution from all gas and oil sources and so the drop will not be as sharp. They may be underestimating the impact of lots of new lift compressors that will be showing up to squeeze the last bits of gas from older wells even as new wells are not drilled as often. But as of Tuesday the link has been made by TCEQ itself that such a drop results in big decreases in smog levels in Denton and Northwest Tarrant County. That's something that citizens can use to argue as proof of the impact of oil and gas facilities on local air quality.

Of course, it only took the span of about 30 minutes for the TCEQ to internally contradict itself about those results.

According to TCEQ computer modelers, natural gas Compressor Stations large enough to be considered "point sources" just like cement kilns or power plants will be responsible for over 17 tons of Nitrogen Oxides, and 26 tons of VOCs a day in 2018 – well over the amount of oil and gas pollution decreases that resulted in those lower monitoring numbers in Denton and NW Tarrant County. But according to the TCEQ staff responsible for suggesting new controls in the new smog plan, those numbers are not large enough to have an impact on improving DFW air quality or warranting a policy of electrification for those compressors that could reduce their air pollution to a fraction of those volumes.

So while 7 tons of NOx reduction from Oil and Gas sources is large enough to bring some of the most stubborn monitors down a whole part per billion, reducing air pollution from Oil and Gas sources by another 17 tons of NOx reduction would have no effect on DFW air quality at all and it's just not worth it to make them electrify compressors. Honest, that was the logic in play on Monday, and it didn't hold up very well under questions from people like Liz Alexander.

And that was all before you got to why the Midlothian cement kilns could not, no way, no how, possibly, under any circumstance, be required to install Selective Catalytic Reduction controls, just like their European counterparts have done over the last 15 years.

Turns out, it's just because.

Oh, the TCEQ staffer cited four criteria for any new control measure to meet before it could be considered. Let's see, there was "technological feasibility." Since there are at least seven full-scale SCR units up and running in Europe, that couldn't be a problem. It's accepted technology by some of the same companies operating kilns in the US – including LaFarge-Holcim.

There was "economic feasibility." And since there are all those SCR examples already in the European market and no company has gone bankrupt running them, that's also off the table. Plus the fact that the TCEQ's own 2005 study of SCR concluded it was "available technology" then that would only cost $1000 to $3,000 per ton of NOx removed – versus the up to $15,000 per ton of NOx removed ratio allowed in the state's own official diesel engine replacement program. Coming in at one-fifth the cost of what the state already said was economically feasible, it certainly ruled out that one.

There was the third criterion – that controls couldn't cause ‘‘substantial widespread and long-term adverse impacts.’’ The state said that wasn't the reason they couldn't be considered either, although the TCEQ staffers seemed to hedge a bit here, seemingly wanting to say that, really, they didn't want to cause themselves adverse impact by admitting that they had been wrong for over a decade about this stuff.

The proposed control cannot be ‘‘absurd, unenforceable, or impracticable.’’ Clearly, if the Europeans are doing it on their kilns, it's none of those either. It's quantifiable, and up and running in power plants, cement kilns and incinerators.

And it has to speed the attainment deadline by a year. No problem. SCR could do that if it was installed in a timely fashion.

So at the end of the state's presentation, former Dallas County Judge Margaret Keliher asked the TCEQ staffer exactly why SCR wasn't considered a possible pollution control measure since none of these criteria that had been presented seem to rule it out. And the TCEQ's staffer's response was…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

No, really, that was the response. She couldn't say. It was that embarrassing. Because the rejection of SCR by TCEQ isn't based on any of those criteria. It's based on a political decision that's been made that no new pollution controls will be sought on the kilns or any other major industrial polluter as long as Rick Perry is running for President. Or "just because."

How ridiculous is this? At this point the TCEQ is taking an even more regressive view of SCR controls than the cement industry itself. In June, Holcim Cement's Midlothian plant requested a permit from the state that would allow it to build either a Thermal Oxidizer or an SCR until for the control of VOC pollution. Being the free market fanatics the Perry Administration claims to be, doesn't the fact that one of the Midlothian cement plants is asking for a permit that includes the possibility of installing SCR mean it's automatically technologically and economically feasible? The market is never wrong, right? Are the folks at Holcim so enamored of kinky, off-the-wall green technology that they'll just include it in a permit for laughs? These guys are Swiss engineers. They have no sense of humor.

Denial of SCR as a viable control measure that could reduce smog pollution is making the TCEQ contort into sillier and sillier positions. It's making them deny the conclusions of their own almost-decade old report that said it was available to put in a kiln in 2005. It's making them deny the fact that SCR is up and running at over half a dozen kilns in Europe. It's forcing them to once again use the "Midlothian limestone is magically special" defense that has been used to forestall any progress in pollution control there over the last 25 years. The arguments used against SCR are exactly the same as were used against the adoption of less effective SNCR technology before it was mandated. In case you hadn't noticed, they're still making cement in Midlothian despite the burden of having to nominally control their air pollution.

The state wants to power through this anti-smog plan just like they did the last one in 2011. They don't want to have to make industry do anything. But at this point the denial of SCR as a control measure to be included in the next DFW anti-smog plan is so absurd, as is the justification for electrification of gas compressors, that it might be fodder in the next citizens lawsuit over a DFW anti-smog plan, which usually follows these things like mushrooms after a rainstorm.

Want to get involved in this fight and make it more difficult for the state to get away with doing nothing at all about DFW smog – again? Please consider attending our next DFW Clean Air Network meeting – THIS SUNDAY, AUGUST 17th, from 3:30 pm to 5:30 pm at the offices of the Texas Campaign for the Environment across from Lee Park in Dallas, 3303 Lee Pkwy, Suite #402 (214) 599-7840. Citizens are the only force that can make this plan better. Be there, or breathe bad air.

Want to Quiz the State Over Crappy DFW Air? Tomorrow’s Your Chance As the Empire Strikes Back

Rick Perry's minions at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) are drafting a new anti-smog plan for DFW this summer and fall. The only access DFW residents have to how it's being done and why are through periodical regional air quality meetings hosted by the Council of Governments in Arlington. At these meetings staff from TCEQ make presentations on why the air in DFW is getting so much better and why no new pollution control measures are needed to reach smog standards required by the Clean Air Act – despite the fact that the state is 0 for 5 in plans to attain compliance with those standards. In fact, the last such plan from Austin actually resulted in slightly higher levels of smog.

Rick Perry's minions at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) are drafting a new anti-smog plan for DFW this summer and fall. The only access DFW residents have to how it's being done and why are through periodical regional air quality meetings hosted by the Council of Governments in Arlington. At these meetings staff from TCEQ make presentations on why the air in DFW is getting so much better and why no new pollution control measures are needed to reach smog standards required by the Clean Air Act – despite the fact that the state is 0 for 5 in plans to attain compliance with those standards. In fact, the last such plan from Austin actually resulted in slightly higher levels of smog.

Tomorrow, Tuesday August 12th there will be another such regional air quality meeting. It's going on from 10 am to 12 noon at the Council of Government headquarters in Arlington at 616 Six Flags Road, right across from the amusement park (insert your own joke here). Of course, it's during business hours – you didn't think they're going to make it easy for the public to attend, did you?

Despite that, beginning in April more and more local residents have been showing up at these meetings to express their concern at the lack of progress in bringing safe and legal air to DFW. One of the reasons is that these meetings are the only forum available to citizens to question TCEQ staff in person – and then ask follow-up questions if you don't like the first answer. It's their only opportunity to be a kind of clean air Perry Mason and because it's a public meeting and everyone's looking at them, TCEQ staff have to at least make an attempt to answer those questions.

Things reached a high point at the last meeting in June when Downwinders and the Sierra Club were allowed to make their own presentations about why the state is falling down on its job. A roomful of concerned citizens and elected officials saw the case against the state was self-evident – all we had to do was quote from its own past press releases and memos to make our point.

Tomorrow's meeting is the first chance the state will have to give a rebuttal to those citizen group presentations. Staff will present all the reasons why we don't need new air pollution controls on the Midlothian cement plants, the gas industry, or the East Texas coal plants, and why another do-nothing anti-smog plan from Austin will be just dandy.

And so, if between inhaler bursts you ever wanted to quiz officials about Rick Perry's air pollution strategies, tomorrow's meeting is going to be your chance.

You may think you're not qualified, but you'd be wrong. Simple common sense questions are often the hardest ones for the TCEQ staff to answer, because you know, they're based on common sense, and so many of their policies aren't.

This is how citizens uncovered the fact that TCEQ was hiding oil and gas pollution in other categories not named oil and gas. This is how we got the TCEQ to release maps of where all the gas industry compressors in DFW are after first explaining there were no such maps. And so on.

All that you need is a curious mind. They're not prepared for those.

Tomorrow, 10 to 12 noon is your opportunity to show your concern about breathing bad air, your desire to see major industrial sources of pollution better controlled, and why you want these anti-smog plans to do more. Be there or keep breathing bad air.

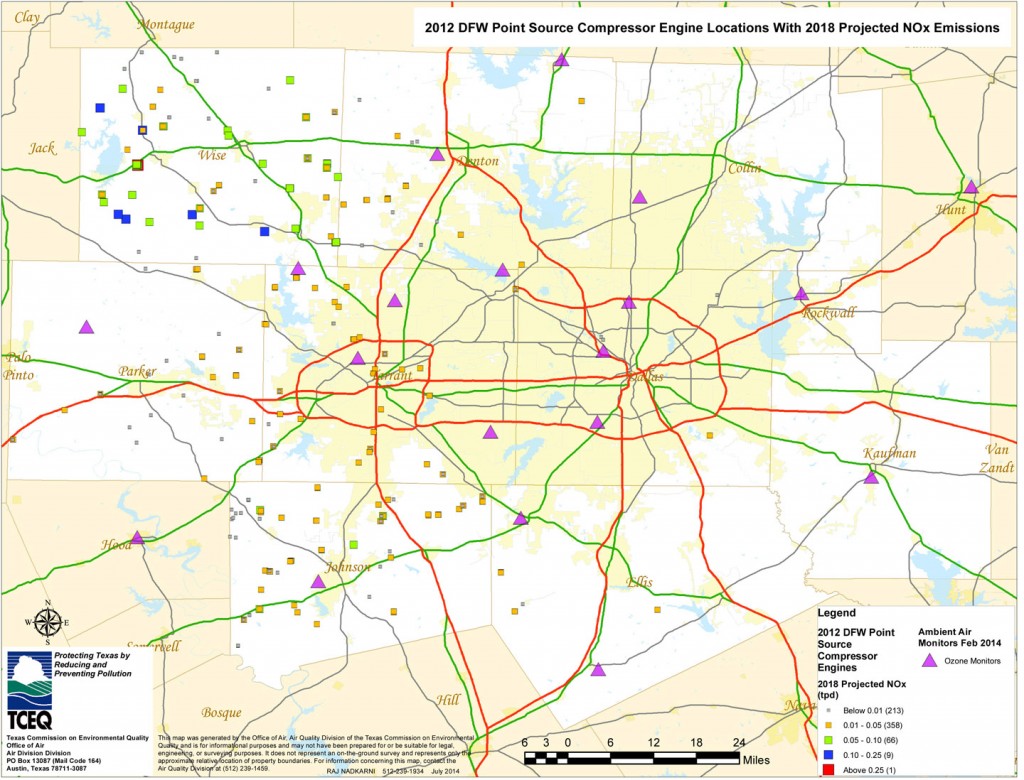

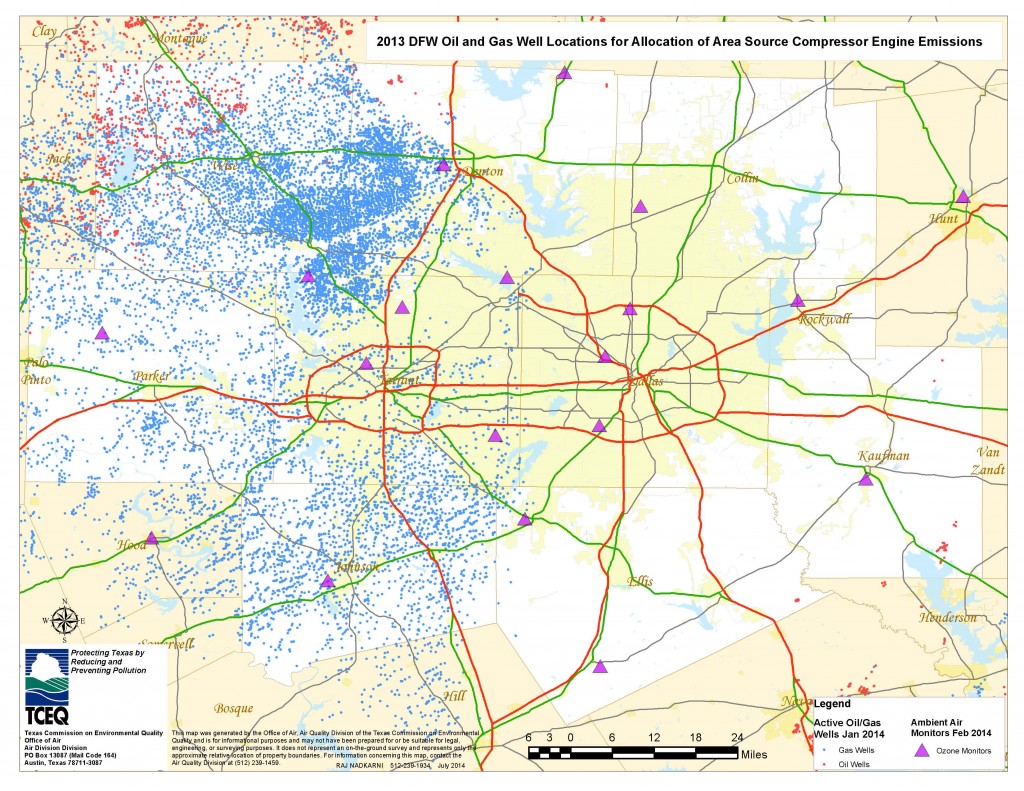

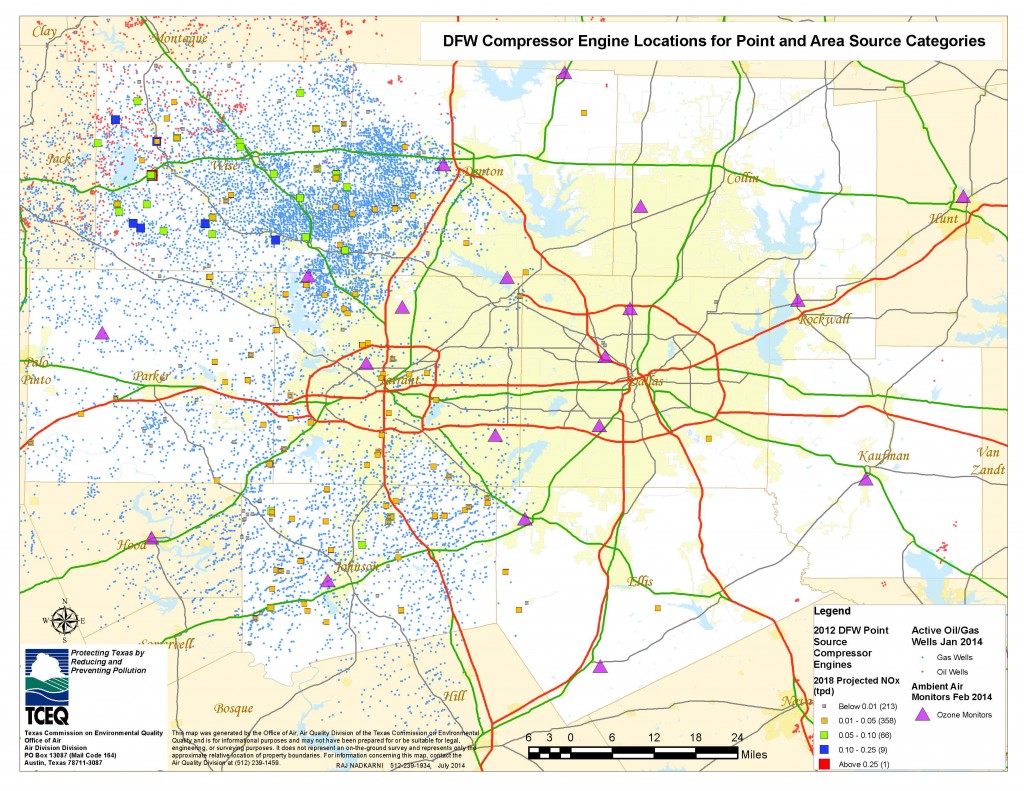

Three Easy Pictures: Why the TCEQ Didn’t Want Compressor Locations Publicized

These are maps that supposedly weren't available…until they were.

These are maps that supposedly weren't available…until they were.

From January all the way through June, citizens involved in watch-dogging the state's drafting of an anti-smog plan for North Texas had been asking if the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality had maps of the locations of all the gas compressors in the 10-county DFW "non-attainment" area for ozone.

The answer from the state, over the course of at least three regional air quality meetings in Arlington, was always no.

Then State Representative Lon Burnam asked the same question, officially, in a letter to TCEQ. About two weeks ago, he got these three maps in the mail. Thanks to Representative Burnam for his follow-though.

This dodge followed an attempt by the state to hide the emissions from these compressors in other categories besides "Oil and Gas" in an attempt to minimize the industry's air pollution impacts on DFW air quality.

You can understand why TCEQ wasn't eager to show these maps.

The first shows the location of 647 large gas compressors. The volume of air pollution from each of these compressors is so large that they're considered "point sources" like power plants, cement plants, manufacturing plants, etc. According to the TCEQ, these larger compressors will be emitting over 14 tons of smog-forming Nitrogen Oxide pollution PER DAY by 2018.

The second shows the approximate location of the thousands of smaller, "area sources" compressors. TCEQ doesn't really know how many of these there actually are – they've never counted and no inventory by industry is required.

Instead, the state bases the number and approximate location of these smaller compressors on the production rates of gas in the Barnett Shale, as reported by the Railroad Commission, and disperses them accordingly.

There's some question about whether this is the most accurate way to take a count – a lot of industry literature says you should use the number of wells and the age of the wells instead of the production rate because as a gas field gets older, operators use more compressors to extract harder-to-get gas.

This is important because while production rates in the Barnett Shale have gone down, the number of wells is increasing.

The upshot is that as impressive as all those dots seem in the second map, they may actually represent an underestimate of the number of smaller compressors on the ground. As it is, TCEQ estimates these compressors will collectively release another six and a half tons of smog-forming Nitrogen Oxides PER DAY by 2018. That's in addition to the pollution of the larger point source compressors.

The last map is a combination of the first two. In all three the region's smog monitors are the purple triangles. Please take note of their location as well.

For over a decade now it's the monitors at the Denton Airport and in Northwest Tarrant County – at Meacham Field, in Keller, in Grapevine and Eagle Mountain Lake – that have recorded the highest smog readings in the entire regions.

There's no question as pollution accumulates over Dallas and Fort Worth and blows Northwest, ozone levels get higher. It's also true the pollution plumes from the Midlothian cement plants can blow directly into the paths of many of these monitors. But can anyone look at these maps and not realize that these gas compressors are also contributing to the high readings being recorded at the monitors in Denton and Northwest Tarrant County?

That's the real reason TCEQ didn't want the public to see these maps.

There's another regional air quality meeting next Tuesday, August 12th in Arlington from 10 am to 12 noon at the North Central Texas Council of Government offices at 616 Six Flags Road. These meetings are the only chance that citizens have to ask questions of TCEQ staff about the information going into drafting the new anti-smog plan. Without those kinds of questions, we still wouldn't know how much air pollution these gas compressors are emitting, or their location. Rep. Burnam would not know what official requests to submit. Information is power. Come get a little more empowered this next Tuesday.