Air Plan

TCEQ’s Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Air Plan for DFW

TCEQ Public Hearing on the new DFW Anti-Smog Plan

Thursday, January 15th 6:30 pm

Arlington City Hall, 101 W. Abram

Over the last two decades, we've seen some pretty lame DFW clean air plans produced by the state, but the newest one, scheduled for a public hearing a week from now, may be the most pathetic of the bunch.

From a philosophical perspective, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality stopped pretending to care about smog in DFW once Rick Perry decided to run for president around 2010 or so. Computer modeling was scaled back, staff was slashed, and the employees that were left had to be ideologically aligned with Perry's demand that no new controls on industry (i.e potential or existing campaign contributors) was preferable to six or seven million people continuing to breathe unsafe and illegal air.

TCEQ's 2011 anti-smog plan reflected that administrative nonchalance by concluding – in the the middle of the Great Recession – that consumers buying new cars would single-handedly deliver the lowest smog levels in decades. It did not. It went down in history as the first clean air plan for the area to ever result in higher ozone levels. The first, but maybe not the last.

This time around, it's not the cars themselves playing the role of atmospheric savior for TCEQ, but the fuel they'll run on. Beginning in 2017, the federal government is scheduled to introduce a new, low-sulfur gasoline that is predicted to bring down smog by quite a bit in most urban areas. Quite a bit, but not enough to reach the ozone standard of 75 ppb that's necessary to comply with the Clean Air Act by 2018. It's the gap between this official prediction and the standard where the state is doing a lot of hemming and hawing.

TCEQ staffers really did tell a summertime audience in Arlington that that estimated 2018 gap of between 1 and 2 ppb was "close enough" to count as a success. Now, you might give them the benefit of the doubt, but remember this is an agency that has never, ever been correct is its estimation of future ozone levels. After five attempts over the last two decades, TCEQ has never reached an ozone standard in DFW by the official deadline. Precedent says this plan won't even get "close enough."

Plus, we know getting "close" to 75 ppb isn't protecting public health in DFW. Even as this clean air plan is being proposed by Austin, the EPA is moving to lower the national ozone standard to somewhere between 60 and 70 ppb (There's a hearing on that at Arlington City Hall on January 29th). That new EPA ozone standard is due to be adopted by the end of this year. So this entire state plan is obsolete from a medical perspective. Instead of aiming for a level of ozone pollution closer to 70 ppb as soon as possible, it's not even getting down to a flat 75 ppb at all DFW monitors by 2018. It wil take an entirely new plan, and pulling TCEQ teeth, to do that much later. In other words, millions of people will have to wait as much as a five to seven years longer to get levels of air quality we know we need now in 2015.

What are the major flaws this time?

1. TCEQ is Using 2006 in 2014 to Predict 2018.

The EPA recommends that states use an "episode" of bad air days from the last three years – 2009-2013 – in trying to estimate what ozone levels will be three years from now. The more recent the data, the better the prediction.

TCEQ is ignoring that recommendation, relying on a computer model that's already nine years old. This has all kinds of ramifications on the final prediction of compliance. Instead of having more recent weather data, you have to "update" that variable. TCEQ doesn't have to compensate for the drought DFW is experiencing now or factor in a year like 2011 where the drought caused a worst case scenario for ozone formation.

TCEQ isn't using more recent data on how sensitive monitors are to Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) – the major kinds of pollution that cause smog . That's important because gas production in the Barnett Shale has put a lot more VOCs in the air. But instead of getting a more accurate post-drilling boom read on what's driving smog creation, the TCEQ is relying on a picture that starts out before the boom ever started.

The further you reach back in time for a model to predict future levels of smog, the fuzzier that future gets, and the less accurate the results. TCEQ is using a model that's twice to three times older than EPA guidance recommends. What are the odds that TCEQ estimates will be correct based on this kind of methodology?

2. TCEQ is Downplaying OIl and Gas Pollution

Citizens attending the air quality meetings in Arlington over the past year have seen the TCEQ try and hide the true volume and impact of oil and gas pollution at every turn. Instead of all the industry emissions being listed under the single banner of "Oil and Gas Pollution," the Commission has tried to disperse and cloak them under a variety of categories in every public presentation.

"Other Point Sources," a classification that had never been seen before, was the place where pollution from the 647 large compressor stations in DFW could be found – if you bothered to ask. "Area Sources" was where the emissions from the thousands of other, smaller compressors could be found – again, only if you asked. "Drilling" was separate from "Production." And despite other agencies being able to tease out what kind of pollution came from the truck traffic associated with fracking within their jurisdictions, the TCEQ never bothered to estimate how much of the emissions under "Mobile Sources" was generated by the Oil and Gas industry.

The reason the TCEQ has tried so hard to hide the true volumes of oil and gas pollution is because once you add up all of these disparate sources, the industry becomes the second largest single category of smog-forming pollution in DFW, second only to on-road cars and trucks (and remember many of those trucks are fracking-related). According to TCEQ's own estimates, oil and gas facilities in North Texas produce more smog-forming VOC pollution than all of the cars and trucks in the area combined, and more smog-forming NOx pollution than the Midlothian cement plants and all the area's power plants combined.

TCEQ is loathe to admit the true size of these emissions and place them side-by-side next to other, traditional sources, lest the public understand just how huge a impact the oil and gas industry has on air quality. Austin's party line is that this pollution isn't contributing to DFW smog – that it's had no impact on local air quality. But such a claim isn't plausible. If cars are a source of smog, and cement kilns and power plants are a source of smog, how can a category of VOC and NOx pollution dwarfing those sources not also be a source of smog? Think how much less air pollution we'd have if the Barnett Shale boom of the last eight years had not taken place?

In it's last public presentation in August, the TCEQ made the impact of oil and gas pollution clear despite itself. According to the staff, oil and gas emissions were going to be decreasing in the future more than they had previously estimated. As a result, a new chart showed that certain ozone monitors, including the one in Denton, would see their levels of smog come down significantly. It was exactly the proof of a causal link between gas and smog that TCEQ had been arguing wasn't there. Only it was.

In terms of forecasting future smog pollution, TCEQ is underplaying the growth of emissions in the gas patch. Everything it's basing its 2018 predictions on is years out-of-date, leftover from its last plan.

Drilling rig pollution is extrapolated from a 2011 report that counts feet drilled instead of the actual number of rigs. TCEQ predicts a decline in drilling and production in the Barnett Shale without actually estimating what that means in terms of the number of wells or their location. It also assumes a huge drop-off in gas pollution after 2009 that hasn't been documented by any updated information. It's only on paper.

While recent declines in the price of oil and gas have certainly put a damper on a lot of drilling activity, there's still a significant amount going on. Look no further than Mansfield, where Edge is now applying for permit to build a new compressor and dozens of new wells on an old pad.

In 2011, nobody was building Liquified Natural Gas terminals up and down the Gulf Coast for an export market the way they are now. Analysts say those overseas markets could produce a "second boom" in drilling activity between now and 2018, but the TCEQ forecasts don't take that into account.

Gas production pollution numbers – emissions from compressors, dehydrators, storage tanks – are even more tenuous. Every gas industry textbook explains that as gas plays get older, the number of lift compressors increases in order to squeeze out more product. Increase the number of compressors and you increase the amount of compressor pollution. But TCEQ numbers fly in the face of that textbook wisdom and predict a decline in compressor pollution because wells in the Barnett Shale are getting older!

The best analogy for how TCEQ is estimating oil and gas pollution is its poor understanding of where those thousands of smaller compressor are and how much pollution they're actually producing. No staff member at TCEQ can tell you how many of those compressors there are in the region – they literally have no idea and no idea of how to count them in the real world. There are just too many, their locations are unknown, and they were never individually permitted.

Instead, the TCEQ takes production figures from the Railroad Commission and guesses how many of those small compressors there are, as well as their location, based on where the RRC tells it production is going on in the Shale. Then staff guesses again about the emissions being emitted by those compressors, because there's no data telling them what those emissions actually are. In the end you have a series of lowballed guestimates, stacked one atop the other, presented as fact. It's smoke and mirrors.

3. TCEQ Isn't Requiring Any New Controls on Any Major Sources of Air Pollution

Like its previous 2011 DFW air plan, which resulted in an increase in North Texas ozone levels, TCEQ's new plan requires no new controls on any major sources of air pollution, despite evidence showing that such controls in smog-forming emissions from the Midlothian cement plants, East Texas coal plants, and Barnett Shale gas facilities could cut ozone levels significantly.

Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) is already used extensively in the cement plant industry in Europe to reduce smog pollution by up to 90%. Over a half dozen different plants have used the technology since 2000. The TCEQ's own 2006 report on SCR concluded it was "commercially available." Holcim Cement has already announced it will install SCR in its Midlothian cement plant. Yet the TCEQ makes no mention of this in its plan.

That's right, a cement plant in Midlothian has decided SCR is commercially viable, but the State is looking the other way and pretending this development in its own backyard isn't even happening. TCEQ is stating in its proposed plan that SCR just isn't feasible!

In 2013, a UTA Department of Engineering study looked at what happened if you reduced Midlothian cement plant pollution by 90% between 6 am and 12 Noon on weekdays. Ozone levels went down in Denton by 2 parts per billion. That may not seem like a lot, but in smog terms it's the difference between the Denton air monitor violating the 75 ppb standard under the TCEQ plan and complying with the Clean Air Act.

In 2012 a UTA College of Nursing study found higher rates of childhood asthma in Tarrant County "in a linear configuration" with the plumes of pollution coming from the Midlothian cement plants. SCR means less pollution of all kinds: smog, dioxins and the particulate matter the Nursing College thought was causing those increased rates of childhood asthma. By delaying the requirement that all the Midlothian cement plants install SCR by 2018, the state is turning its back on a problem that Cook Children's hospital described as "an epidemic."

The same is true of SCR in the East Texas coal plants. The technology is being used in other coal plants around the world and in the US to reduce smog pollution. There's no reason it shouldn’t be required for the dirtiest coal plants in Texas that impact DFW air quality. After decades of being out of compliance with the Clean Air Act, DFW is one of the places the technology is needed most.

Last year the Dallas County Medical Society, led by Dr. Robert Haley, petitioned the TCEQ to either close those coal plants or install SCR on them. The doctors' petition was rejected by TCEQ Commissioners and they were told their concerns would be addressed in the DFW air plan. They aren't. Those concerns, along with the proof they presented about the impact of the plants on local air quality, are being ignored.

Electrification of gas compressors is a commonly used technology that could cut smog pollution as well, and yet the TCEQ is not requiring new performance standards that would force operators of hundreds of diesel and gas-powered compressors in North Texas to switch to electricity.

A 2012 Houston Advanced Research Center study found that pollution from a single compressor could raise local ozone levels by as much as 3 to 10 ppb as far away as ten miles. There are at least 647 large compressor stations in the western part of the DFW area. Dallas and other North Texas cities have written ordinances requiring only electric-powered compressors within their city limits based on testimony from industry that electrification was a commonly used technology in the industry. And yet, TCEQ's official position is that electrification isn't feasible.

In ignoring these types of new controls the TCEQ is violating provisions of the Clean Air Act to implement "all reasonably available control technologies and measures" to insure a speedy decrease in ozone levels. Each of these technologies is on the market, being used in their respective industries, and readily available. Studies have shown that each of these technologies could cut ozone levels in DFW significantly, but the TCEQ is refusing to implement them. In doing so, many observers believe it's blatantly in violation of the law.

We don't expect TCEQ to change its position. That well has been poisoned for the foreseeable future. But we do expect a higher standard of enforcement from the Obama Administration EPA. That's why we're asking you to show-up at the public hearing and oppose this dreadful state air plan a week from now in Arlington. We need to demonstrate to the federal government that citizens are concerned about getting cleaner air now, not in the next plan or the one after that. Now. We need to put pressure on the EPA to reject this TCEQ plan, to either send it back to the drawing board or substitute one of its own. Without you showing up, that pressure isn't there.

Between now and Thursday – and all the way through January 30th, you can send prepared comments opposing the TCEQ plan to Austin and the EPA Regional Administrator with a simple click here – and add your own comments as well.

As a reward for coming over and venting your frustration, we'd like you to stay and party with us at the official "retirement party" of State Representative Lon Burnam, beginning at 7:30 pm just four blocks down the street. It's a roasting and toasting of the best friend environmentalists ever had in the Texas Legislature, as well as a fundraiser for Downwinders to continue our work to defend your air. JUST CLICK HERE FOR TICKETS.

Next Thursday you can support clean air two ways in one evening. Help us beat back a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad air plan, and then come celebrate the wonderful, righteous, very good work of a dedicated public servant. See you there.

2014 DFW Smog Report: Good News But Don’t Hang Up the Gas Mask Yet

For the first time since DFW began recording its smog levels, the region's three-year running average dipped below the 1997 eight-hour 85 parts per billion (ppb) standard. After years of leveling off at around 86-87, it's dropped to 81 ppb. That's good news.

For the first time since DFW began recording its smog levels, the region's three-year running average dipped below the 1997 eight-hour 85 parts per billion (ppb) standard. After years of leveling off at around 86-87, it's dropped to 81 ppb. That's good news.

DFW's decrease is attributed to 2011's terrible numbers rolling off the board and a wetter, cooler and windier summer than normal these last five months or so. As both drought-ridden 2011 and this year's results demonstrate, weather still plays an extremely critical role in how large or small our smog problem will be. Another summer or two like 2011 could easily put us back over the 1997 standard. More wet and cooler weather could see the decrease continue.

The news would be better except that we were supposed to have originally accomplished this milestone in 2009, then again last year after a second try, according to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

As it is, we still haven't reached the current, more protective 2008 national standard that was revised downward to 75 ppb after a review of the scientific literature.

In January, TCEQ will host a public hearing on its proposed "plan" to EPA to meet that goal that predicts most, but not all DFW monitors will reach 75 ppb by the summer of 2018.

Despite overwhelming evidence that new controls on the Midlothian cement plants and the reduction of gas industry pollution could speed this achievement, TCEQ's new plan contains no new pollution control measures on any major sources of smog polluters – cement kilns, coal plants, gas sources – but instead relies on the federal adoption of a new lower-sulfur gasoline mix for on-road vehicles. Like past proposals by Rick Perry's TCEQ, this one depends solely on the feds to get them into compliance. TCEQ isn't lifting a regulatory finger to help.

And its new plan once again aims high, not low. At last count, there were at least three Tarrant and Denton County monitors that TCEQ admitted would still be above the 75 ppb standard at the end of 2018. "Close enough" is the reply from Austin.

From a public health perspective, it's even worse. Why does the ozone standard keep routinely going down? Because new and better evidence keeps accumulating to show widespread health problems at levels of exposure to smog that were once considered "safe." About every five years, the EPA's scientific advisory committee must assess the evidence and decide if a new standard needs to be enforced to protect public health.

For most of the last ten years, the position of this independent panel of scientists is that the standard should be somewhere between 60 and 70 ppb. They were ignored in 2008. They were ignored in 2011. They once again came to this conclusion last May. What was the evidence that persuaded them? That the current 75 ppb standard for smog causes almost 20% of children in "non-attainment areas" to have asthma attacks, and leads to hundreds of thousands of deaths every year. Cutting the standard to 60 ppb reduces those deaths by 95%. Since the Clean Air Act states the EPA is duty bound to set a smog standard protective of human health, 60 ppb seems to be the threshold level that the current scientific literature says is actually safe for the majority of the population most vulnerable to the impact of bad air. By contrast, a smog level of 70 ppb only reduces those deaths by 50%. (Policy Assessment for the Review of the Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standard, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air and Radiation, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Health and Environmental Impacts Division, Ambient Standards Group, August 2014)

By December 1st, EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy must decide whether to officially recommend a standard in that 60-70 ppb range. It looks as though this time, the EPA might just endorse what the scientists are recommending, although it's unclear whether it'll be the upper or lower part of that range.

So even while the TCEQ is saying it's "close enough" to achieving the 75 ppb standard left over from George W's administration by 2018, the evidence is that level is too high to prevent large public health harms and must be lowered. A lot.

This is why it's so infuriating that the TCEQ is satisfied with getting only "close enough" to a 2008 standard that's about to become obsolete. Austin knows it could demand better air pollution control measures on the market right now that would accelerate the decrease in smog. It knows the pubic health would benefit from requiring such measures. But it's willing to condemn DFW children and others at risk for many more years for the sake of keeping its "business-friendly" reputation.

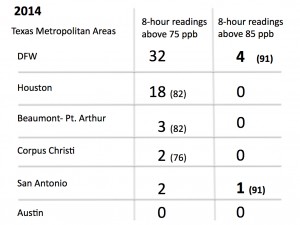

And while this year's slip below the 85 ppb standard is a sign of some progress, it remains true that DFW still has the worst air in Texas – a title we took from Houston years ago. Take a look at the chart summarizing the 2014 ozone season across Texas. Despite the nicer weather, DFW still had almost twice as many readings above 75 ppb as Houston and four above the 85 ppb standard. Houston had no readings above 85. In fact, San Antonio was the only other city to record a level so high – once.

DFW still has a smog problem and all it takes is another hot and dry summer to see it escalate. We need the help more controls on major sources could give us. We need Selective Catalytic Reduction on ALL the Midlothian cement and East Texas coal plants. We need electrification of gas compressors in the Barnett Shale. This should be the message to both the TCEQ and EPA during the public hearing in January.

DFW still has a smog problem and all it takes is another hot and dry summer to see it escalate. We need the help more controls on major sources could give us. We need Selective Catalytic Reduction on ALL the Midlothian cement and East Texas coal plants. We need electrification of gas compressors in the Barnett Shale. This should be the message to both the TCEQ and EPA during the public hearing in January.

DFW smog in 2014: we've met the Clinton era standard for now, on the way to trying to get "close enough" to the W Standard, and still very far from a new Obama standard. Don't hang up the gas mask yet.

TCEQ: Link Between Fracking and Air Quality, No Cement Controls Just “Because”: Highlights From Tuesday’s Air Meeting

Dallas Resident Liz Alexander showed up at the Council of Governments meeting room on Tuesday to lend her support to the effort to get more out of an anemic state ant-smog plan than the state wants to give. She was a warm body whose presence would be its own statement of concern. She was being a good trooper by just showing up.

Dallas Resident Liz Alexander showed up at the Council of Governments meeting room on Tuesday to lend her support to the effort to get more out of an anemic state ant-smog plan than the state wants to give. She was a warm body whose presence would be its own statement of concern. She was being a good trooper by just showing up.

At first she sat far from the action amidst the rows of seats for bystanders and, despite encouragement, was resigned to just listening, because as she explained, "she didn't know enough to ask questions."

Then someone urged her to move up to the rectangle of tables where the presenters stand and deliver, where there are microphones to raise the volume of concerns and questions that might be posed by mind-numbing reassurances that everything is going hunky-dory. As more of these air quality meetings have occurred, citizens have been less and less shy about taking up these front row seats that look more official than the rest; look like they should be reserved for guys in suits. Increasingly they're occupied by people in street clothes.

And then, after much information had been paraded in front of Liz, she did something she did not think she was qualified to do only about 90 minutes earlier. She asked a question. It was about what assumptions had been included in the information about unspent air pollution clean-up dollars that are piling up in Austin. She got an answer from a local COG staff person in real time that satisfied her. In the space of one meeting she moved from spectator to participant.

And she wasn't the only one. More than any other meeting so far, this one involved more citizens asking more questions about more subjects – and it revealed just how thin the state's rationale is for doing nothing.

As predicted, it was a day for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to explain why its new DFW anti-smog plan was really going to work this time – unlike the five previous failures – and why it wasn't going to be considering any new controls on the Midlothian cement plants or on gas compressors – a refutation of the case Downwinders at Risk had made in its June 16th presentation.

But here's what really happened: For the first time in these proceedings the state admitted that oil and gas emissions have a big influence on regional air quality. And when a former County Judge asked an TCEQ's Air Quality Manager specifically why anti-smog controls already being used on cement kilns in Europe were not being considered for the Midlothian kilns, the staffer couldn't say, offering up only the longest, most pregnant pause by any state staffer in the history of these meetings.

After being heavily criticized for months for leaving at least four monitors above the 75 ppb federal smog standard even after its plan had ended in 2018, the state came back to this meeting saying they only had three sites above 75 ppb now, and by margins that didn't exceed the standard by more than 1 part per billion. Between June and August, there had been a remarkable drop in future estimated smog levels at the area's monitoring sties in the state's computer modeling – particularly at the historically most stubborn monitoring sites in Denton and Northwest Tarrant County.

What had caused this drop? A relatively modest decrease in Nitrogen Oxide pollution of around seven tons a day and a decrease in Volatile Organic Compounds of about 15 tons per day. That's not a lot of pollution to produce such a large decrease in monitor readings in the computer model.

A more important question is: where did the decreases in air pollution come from that could produce such dramatic results in the modeling? The answer: primarily from oil and gas industry sources. Based on TCEQ's own formula relying on the declining number of new wells being drilled in the Barnett Shale.

For the moment forget the methodological qualms you might have about that declining well assumption. Instead, appreciate the fact that the same state agency that couldn't bring itself to ever say the Barnett Shale was producing air pollution holding DFW back from meeting Clean Air Act smog standards now says that it's decreases in that very kind of pollution that are having such a substantial effect on the monitors in the western part of the Metromess that have been the most resistant to other control strategies. TCEQ has just proven a causal link its been denying for over seven years now.

It can't be just a one-way street. If declining oil and gas air pollution equals better air quality in the TCEQ's computer model, so increases in oil and gas pollution must lead to worse air quality.

There are all kinds of reasons to doubt that the drop in total oil and gas air pollution will happen at all or drop as fast or as sharply as the TCEQ predicts. Afterall, they're 0 for 5 in such matters. They may be underestimating the amount of total air pollution from all gas and oil sources and so the drop will not be as sharp. They may be underestimating the impact of lots of new lift compressors that will be showing up to squeeze the last bits of gas from older wells even as new wells are not drilled as often. But as of Tuesday the link has been made by TCEQ itself that such a drop results in big decreases in smog levels in Denton and Northwest Tarrant County. That's something that citizens can use to argue as proof of the impact of oil and gas facilities on local air quality.

Of course, it only took the span of about 30 minutes for the TCEQ to internally contradict itself about those results.

According to TCEQ computer modelers, natural gas Compressor Stations large enough to be considered "point sources" just like cement kilns or power plants will be responsible for over 17 tons of Nitrogen Oxides, and 26 tons of VOCs a day in 2018 – well over the amount of oil and gas pollution decreases that resulted in those lower monitoring numbers in Denton and NW Tarrant County. But according to the TCEQ staff responsible for suggesting new controls in the new smog plan, those numbers are not large enough to have an impact on improving DFW air quality or warranting a policy of electrification for those compressors that could reduce their air pollution to a fraction of those volumes.

So while 7 tons of NOx reduction from Oil and Gas sources is large enough to bring some of the most stubborn monitors down a whole part per billion, reducing air pollution from Oil and Gas sources by another 17 tons of NOx reduction would have no effect on DFW air quality at all and it's just not worth it to make them electrify compressors. Honest, that was the logic in play on Monday, and it didn't hold up very well under questions from people like Liz Alexander.

And that was all before you got to why the Midlothian cement kilns could not, no way, no how, possibly, under any circumstance, be required to install Selective Catalytic Reduction controls, just like their European counterparts have done over the last 15 years.

Turns out, it's just because.

Oh, the TCEQ staffer cited four criteria for any new control measure to meet before it could be considered. Let's see, there was "technological feasibility." Since there are at least seven full-scale SCR units up and running in Europe, that couldn't be a problem. It's accepted technology by some of the same companies operating kilns in the US – including LaFarge-Holcim.

There was "economic feasibility." And since there are all those SCR examples already in the European market and no company has gone bankrupt running them, that's also off the table. Plus the fact that the TCEQ's own 2005 study of SCR concluded it was "available technology" then that would only cost $1000 to $3,000 per ton of NOx removed – versus the up to $15,000 per ton of NOx removed ratio allowed in the state's own official diesel engine replacement program. Coming in at one-fifth the cost of what the state already said was economically feasible, it certainly ruled out that one.

There was the third criterion – that controls couldn't cause ‘‘substantial widespread and long-term adverse impacts.’’ The state said that wasn't the reason they couldn't be considered either, although the TCEQ staffers seemed to hedge a bit here, seemingly wanting to say that, really, they didn't want to cause themselves adverse impact by admitting that they had been wrong for over a decade about this stuff.

The proposed control cannot be ‘‘absurd, unenforceable, or impracticable.’’ Clearly, if the Europeans are doing it on their kilns, it's none of those either. It's quantifiable, and up and running in power plants, cement kilns and incinerators.

And it has to speed the attainment deadline by a year. No problem. SCR could do that if it was installed in a timely fashion.

So at the end of the state's presentation, former Dallas County Judge Margaret Keliher asked the TCEQ staffer exactly why SCR wasn't considered a possible pollution control measure since none of these criteria that had been presented seem to rule it out. And the TCEQ's staffer's response was…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

No, really, that was the response. She couldn't say. It was that embarrassing. Because the rejection of SCR by TCEQ isn't based on any of those criteria. It's based on a political decision that's been made that no new pollution controls will be sought on the kilns or any other major industrial polluter as long as Rick Perry is running for President. Or "just because."

How ridiculous is this? At this point the TCEQ is taking an even more regressive view of SCR controls than the cement industry itself. In June, Holcim Cement's Midlothian plant requested a permit from the state that would allow it to build either a Thermal Oxidizer or an SCR until for the control of VOC pollution. Being the free market fanatics the Perry Administration claims to be, doesn't the fact that one of the Midlothian cement plants is asking for a permit that includes the possibility of installing SCR mean it's automatically technologically and economically feasible? The market is never wrong, right? Are the folks at Holcim so enamored of kinky, off-the-wall green technology that they'll just include it in a permit for laughs? These guys are Swiss engineers. They have no sense of humor.

Denial of SCR as a viable control measure that could reduce smog pollution is making the TCEQ contort into sillier and sillier positions. It's making them deny the conclusions of their own almost-decade old report that said it was available to put in a kiln in 2005. It's making them deny the fact that SCR is up and running at over half a dozen kilns in Europe. It's forcing them to once again use the "Midlothian limestone is magically special" defense that has been used to forestall any progress in pollution control there over the last 25 years. The arguments used against SCR are exactly the same as were used against the adoption of less effective SNCR technology before it was mandated. In case you hadn't noticed, they're still making cement in Midlothian despite the burden of having to nominally control their air pollution.

The state wants to power through this anti-smog plan just like they did the last one in 2011. They don't want to have to make industry do anything. But at this point the denial of SCR as a control measure to be included in the next DFW anti-smog plan is so absurd, as is the justification for electrification of gas compressors, that it might be fodder in the next citizens lawsuit over a DFW anti-smog plan, which usually follows these things like mushrooms after a rainstorm.

Want to get involved in this fight and make it more difficult for the state to get away with doing nothing at all about DFW smog – again? Please consider attending our next DFW Clean Air Network meeting – THIS SUNDAY, AUGUST 17th, from 3:30 pm to 5:30 pm at the offices of the Texas Campaign for the Environment across from Lee Park in Dallas, 3303 Lee Pkwy, Suite #402 (214) 599-7840. Citizens are the only force that can make this plan better. Be there, or breathe bad air.

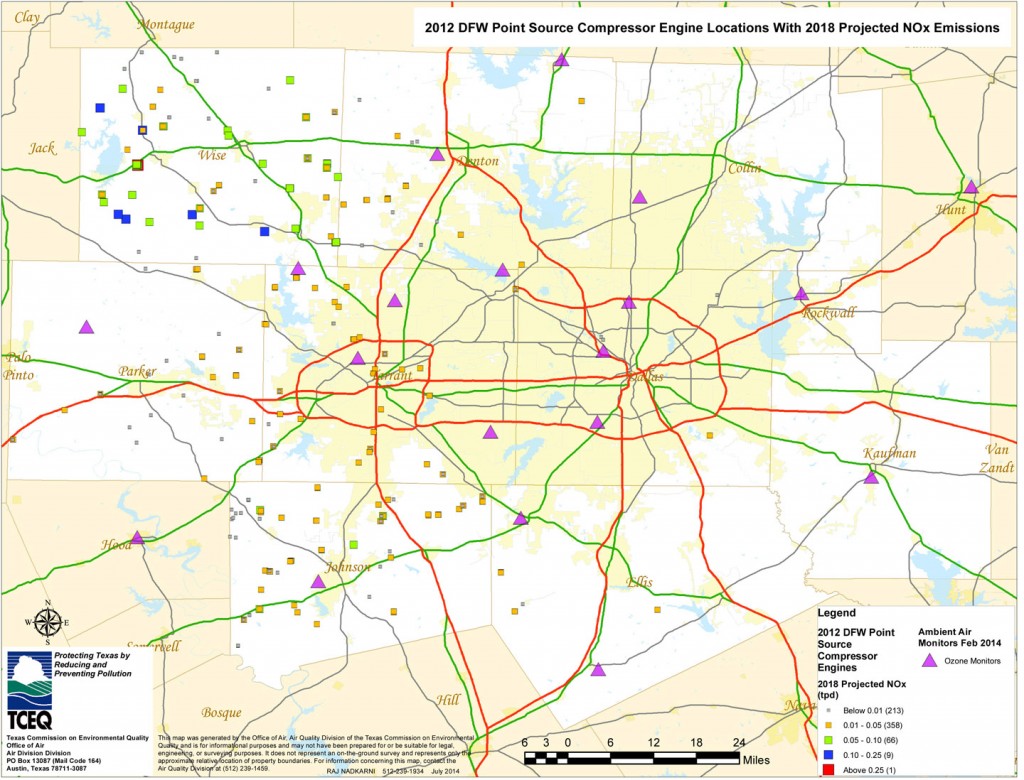

Three Easy Pictures: Why the TCEQ Didn’t Want Compressor Locations Publicized

These are maps that supposedly weren't available…until they were.

These are maps that supposedly weren't available…until they were.

From January all the way through June, citizens involved in watch-dogging the state's drafting of an anti-smog plan for North Texas had been asking if the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality had maps of the locations of all the gas compressors in the 10-county DFW "non-attainment" area for ozone.

The answer from the state, over the course of at least three regional air quality meetings in Arlington, was always no.

Then State Representative Lon Burnam asked the same question, officially, in a letter to TCEQ. About two weeks ago, he got these three maps in the mail. Thanks to Representative Burnam for his follow-though.

This dodge followed an attempt by the state to hide the emissions from these compressors in other categories besides "Oil and Gas" in an attempt to minimize the industry's air pollution impacts on DFW air quality.

You can understand why TCEQ wasn't eager to show these maps.

The first shows the location of 647 large gas compressors. The volume of air pollution from each of these compressors is so large that they're considered "point sources" like power plants, cement plants, manufacturing plants, etc. According to the TCEQ, these larger compressors will be emitting over 14 tons of smog-forming Nitrogen Oxide pollution PER DAY by 2018.

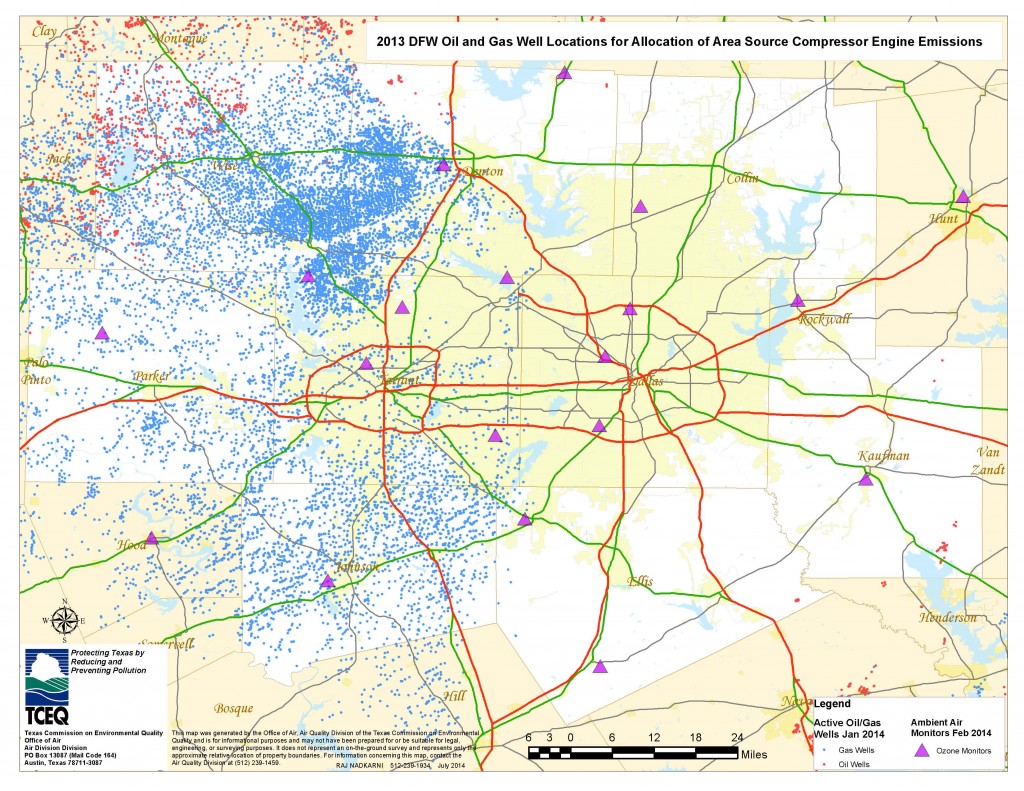

The second shows the approximate location of the thousands of smaller, "area sources" compressors. TCEQ doesn't really know how many of these there actually are – they've never counted and no inventory by industry is required.

Instead, the state bases the number and approximate location of these smaller compressors on the production rates of gas in the Barnett Shale, as reported by the Railroad Commission, and disperses them accordingly.

There's some question about whether this is the most accurate way to take a count – a lot of industry literature says you should use the number of wells and the age of the wells instead of the production rate because as a gas field gets older, operators use more compressors to extract harder-to-get gas.

This is important because while production rates in the Barnett Shale have gone down, the number of wells is increasing.

The upshot is that as impressive as all those dots seem in the second map, they may actually represent an underestimate of the number of smaller compressors on the ground. As it is, TCEQ estimates these compressors will collectively release another six and a half tons of smog-forming Nitrogen Oxides PER DAY by 2018. That's in addition to the pollution of the larger point source compressors.

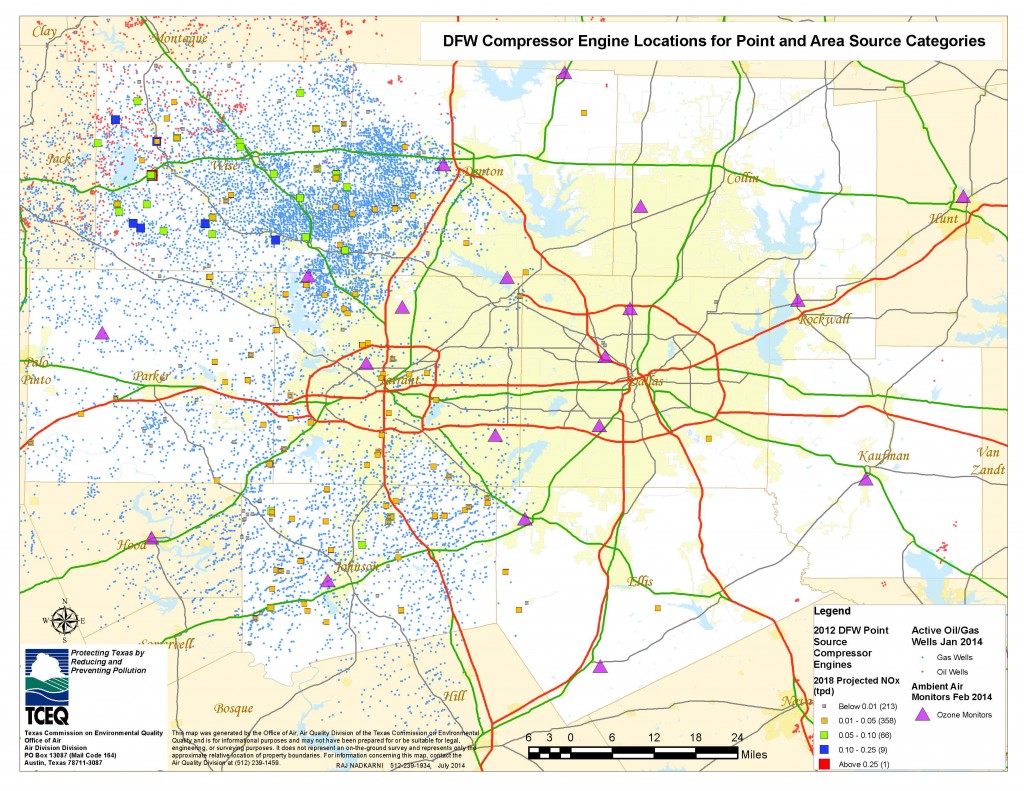

The last map is a combination of the first two. In all three the region's smog monitors are the purple triangles. Please take note of their location as well.

For over a decade now it's the monitors at the Denton Airport and in Northwest Tarrant County – at Meacham Field, in Keller, in Grapevine and Eagle Mountain Lake – that have recorded the highest smog readings in the entire regions.

There's no question as pollution accumulates over Dallas and Fort Worth and blows Northwest, ozone levels get higher. It's also true the pollution plumes from the Midlothian cement plants can blow directly into the paths of many of these monitors. But can anyone look at these maps and not realize that these gas compressors are also contributing to the high readings being recorded at the monitors in Denton and Northwest Tarrant County?

That's the real reason TCEQ didn't want the public to see these maps.

There's another regional air quality meeting next Tuesday, August 12th in Arlington from 10 am to 12 noon at the North Central Texas Council of Government offices at 616 Six Flags Road. These meetings are the only chance that citizens have to ask questions of TCEQ staff about the information going into drafting the new anti-smog plan. Without those kinds of questions, we still wouldn't know how much air pollution these gas compressors are emitting, or their location. Rep. Burnam would not know what official requests to submit. Information is power. Come get a little more empowered this next Tuesday.

Power of the Press: Week after Trib Report on DFW Smog, First “Exceedences” of 1997 Standard

It was only eight days ago the that online Texas Tribune did the first real overview of DFW air quality for this "ozone season." Borrowing heavily from the June 16th Downwinders at Risk presentation to the North Texas regional air quality committee, it concluded that there had been no discernible progress in regional air quality for the past five to six years despite a new state anti-smog plan aimed at getting the area below the 1997 standard of 85 parts per billion.

It was only eight days ago the that online Texas Tribune did the first real overview of DFW air quality for this "ozone season." Borrowing heavily from the June 16th Downwinders at Risk presentation to the North Texas regional air quality committee, it concluded that there had been no discernible progress in regional air quality for the past five to six years despite a new state anti-smog plan aimed at getting the area below the 1997 standard of 85 parts per billion.

Ironically, up to that point, DFW had been enjoying one of the wettest, coolest, most ozone alert-free summers on record. Not one 100 degree day until July and only one "bad air" days of note on June 11th. It looked like we might actually be able to meet the 1997 standard of 85 ppb for the very first time.

That's all changed with this past weeks' return to familiar form. In just seven days, they've been at least four official "ozone alerts" issued for DFW by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Those had produced four "exceedences" of the current 75 parts ppb standard, which the state is now aiming at with another "do nothing" plan under development and due out by the end of the year. On Wednesday the trend got more serious with the addition of the first two "exceedences" of the older 1997 standard we can't seem to conquer – a reading of 88 ppb at the NW Fort Worth monitor at Meacham Field and a 91 at the usually quiet Granbury monitor in Hood County. In the latter case, one mid-afternoon hourly reading reached as high as 113 – just 12ppb short of a violation of an even more ancient standard left over from the 1980's.

For comparison's sake, EPA scientists just sent a letter to EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy recommending that a new, lower federal standard for ozone be set at 60-70 ppb.

It will still take another week of 85 ppb plus days to produce the "fourth highest" readings at the Denton or Keller sites to combine with their 2013 averages and keep DFW in violation of a 17-year old ozone standard. But then again, we have all of August and September to go.

Not surprisingly, two of this summer's hot spots include traditionally troublesome monitors – the Denton and NW Fort Worth site. Tarrant and Denton Counties have historically been the places where the region's highest readings have originated. One reason is wind direction – smog accumulates from upwind sources like the Midlothian cement plants and blows Northwest during the summer. Another more recent reason is the mining of Barnett Shale gas deposits that release huge quantities of smog-forming pollution in the western half of the Metromess, a phenomenon that's been examined in a new UNT study that divided the region's ozone monitors into "Fracking" and "Non-Fracking" areas and found significantly higher readings among those in the Fracking area.

As we went to press with this post, Thursday's readings looked to be producing another round of 75 ppb or higher results. Adding to this year's ozone season irony is that over the last 20 years, July has traditionally been the summer month that produced the fewest number of high ozone readings, book-ended by higher numbers in June and August-September.

Depending on the weather, DFW may still be able to make it over the 1997 standard, 85 ppb hump. But based on this past week's results, that hump just got bigger. Stay tuned.

EPA Scientists Say Current Smog Standard Not Protective Of Public Heath Even While TCEQ Blows Off Current One

It's been a pretty nice summer in DFW so far hasn't it? Wetter and cooler than usual. More wind. According to the stats, this past month was the first June without any 100 degree days in seven years or so. Consequently, it's also the first June in forever that hasn't seen any "Orange" or "Red" ozone alert days. If this keeps up, DFW may actually come into compliance with the 1997 ozone standard of 85 parts per billion (ppb) over an 8-hour time period – a first as well.

It's been a pretty nice summer in DFW so far hasn't it? Wetter and cooler than usual. More wind. According to the stats, this past month was the first June without any 100 degree days in seven years or so. Consequently, it's also the first June in forever that hasn't seen any "Orange" or "Red" ozone alert days. If this keeps up, DFW may actually come into compliance with the 1997 ozone standard of 85 parts per billion (ppb) over an 8-hour time period – a first as well.

But unless you think "global weirding" is going to produce these kinds of summers routinely from here on out, there's little cause for comfort. This year's cleaner air is a direct result of cooler weather. Substitute the hellish summer of 2011 for this mild one and you'd be seeing ozone alerts filling up your e-mail box. As a result, it's not out of the question we could meet the standard this year, but flunk it in 2015 if the weather reverts back to "normal."

In addition, while we may come in under the 1987 smog standard for the first time, the public health goal posts have moved with better science. In 2008, the Bush Administration lowered the acceptable level of smog to 75 ppb. That's the goal of the clean air plan that Downwinders and other groups are fighting the state over right now, saying it's not adequate to even get to that 75 ppb level.

Texas Commission on Environmental Quality staff say we don't need to implement any major pollution control measures on cement kilns, power plants, or natural gas facilities to reach this 75 ppb goal by the deadline in 2018. All we have to do is sit back and let a new federal gasoline standard hit the market in 2017 and we'll all be fine – well, except for those millions of residents who'll be breathing-in smog greater than 75 ppb on the north and western side of the Metromess. But the TCEQ staff say we'll be "close enough." No harm, no foul say the folks from the agency where smog is not considered bad for you.

But close enough should only count in horseshoes and hand grenades, not what people breathe into their lungs. And while some of us are trying to make sure the new TCEQ plan is serious about reaching an air quality goal that's now six years old, the level of ozone considered "safe" by experts is once again going down.

In a letter to EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy last week, the Agency's own Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC) recommended a new smog standard of between 60 and 70 ppb, saying that there's a boatload of evidence showing that the 75 ppb level is not protective of human health, and even at 70 ppb there's significant public health harm done by bad air.

"At 70 ppb, there is substantial scientific evidence of adverse effects….including decrease in lung function, increase in respiratory symptoms, and increase in airway inflammation. Although a level of 70 ppb is more protective of public health than the current standard, it may not meet the statutory requirement to protect public health with an adequate margin of safety….our policy advice is to set the level of the standard lower than 70 ppb within a range down to 60 ppb…"

This recommendation was not unexpected. Every five years, the CASAC is legally obligated to review the scientific literature to make sure the federal ozone standard is giving adequate protection to public health. The last time it did so in 2008, the panel came to a similar conclusion to lower it somewhere between 65 and 70 ppb, but the Bush Administration ignored its own scientists and chose the higher standard instead. An Obama EPA was supposed to correct that mistake when it came into office, but then-EPA head Lisa Jackson got mugged on her way to the White House by the President's re-election campaign. Any changes were put on hold until that five year review clock began ticking again. And now the official alarm has gone off on that clock. The result is a re-affirmation of the earlier findings, this time with even more science to back up the changes.

As a result, EPA will have to decide whether or not to adopt the tougher recommendations of its scientists by December 1st of this year. If they do, a new standard will be officially adopted by 2015 and we'll have to write a new clean air plan in a couple of years to achieve that goal by the end of the decade. If it doesn't, they'll be sued, with the CASAC letter as exhibit #1, and they'll lose and have to set a new standard anyway.

Why is that important to the current debate over TCEQ's plan to meet the 75 standard? Because the TCEQ plan leaves at least four monitors, spread out from Denton, to Keller, to Eagle Mountain Lake above 75 ppb – a standard that EPA scientists now say conclusively is not protecting public health.

"Close enough" to that 75 ppb level turns out to be too far away from real protection in light of the new recommendations for a standard below 70 ppb from the Science Advisory Committee. And that assumes you believe the computer modeling TCEQ has done to support its plan. To date, the state is 0 for 5 going back to 1991 in being able to accurately predict these things. If history is any indication, the state's plan will fail to reach its goal of 75 ppb at just about every one of the 20 monitors in DFW, not just four.

If you know your target of 75 ppb of smog over an 8-hour period is no longer a safe standard, and your current plan condones levels above that, it's not really a clean air plan.

December is not only when EPA must decide if it's going to pursue a lower smog standard. It's also when the state is scheduled to take public comment on its current DFW anti-smog plan. So you have the surreal possibility of holding public hearings over the merits of an already obsolete plan that isn't even serious about reaching its obsolete goal.

This is why DFW residents must demand a plan from Austin that aims lower, not higher. It's why they must demand the EPA not allow TCEQ to get away with being "close enough" to a standard that's not protecting their health. A real clean air plan would be shooting for an average of 65-70 ppb knowing that that standard will be coming down the road sooner or later. A real clean air plan wouldn't allow any monitor to exceed the current 75 standard. A real clean air plan would try to do its best to protect public health by implementing pollution control measures on the sources of smog that are the cheapest and most effective to target – Midlothian's cement plants, east and central Texas coal plants, and the natural gas industry.

And that's exactly what Downwinders and other members of the new DFW Clean Air Network are trying to do. We're pushing for stricter EPA enforcement of the 75 ppb standard, and we're pushing for adoption of "Reasonably Available Control Measures" on the cement plants and gas compressors – now, not later. Because the only way DFW breathers are going to get a better clean air plan out of Austin and Washington is by organizing for one themselves.

Study: Climate Change Will Likely Increase DFW Smog

Just last week at the June regional air quality planning meeting the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality was bemoaning the fact that the weather too often determines how bad an "ozone season" DFW will have. And it's true. When we have really hot, dry, and windless summers, ozone levels soar as they did as recently as 2011-2012 when the recent drought seemed to reach its most awful heights in DFW. Conversely, when we have relatively cool, wet and windy summers, ozone levels abate, as they seem to be doing this year – at least so far.

Just last week at the June regional air quality planning meeting the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality was bemoaning the fact that the weather too often determines how bad an "ozone season" DFW will have. And it's true. When we have really hot, dry, and windless summers, ozone levels soar as they did as recently as 2011-2012 when the recent drought seemed to reach its most awful heights in DFW. Conversely, when we have relatively cool, wet and windy summers, ozone levels abate, as they seem to be doing this year – at least so far.

Of course, the TCEQ spokesperson was using weather as an excuse why DFW hadn't yet achieved compliance with the 1997 ozone standard after two tries that fell short. Completely overlooked was the fact that the last state air plan for DFW in 2011 promised historically low ozone levels by 2013 without any new pollution controls on major sources of pollution. Combine that lack of action with a really hot, dry summer like we saw in 2011, and you get the first clean air plan ever to leave ozone levels higher after it ended than when it started.

That's why it's important to think about the weather when you're trying to build new clean air plans for DFW that stretch years into the future. Air quality planners have to ask themselves if between now and the next federal clean air plan deadline of 2018, will there be more summers like this seemingly anomalous one, or will they more like the summer of 2011 when we had a constant barrage of 100 degree plus days as early as March?

Currently, the TCEQ is using a stretch of bad air days from 2006 to predict ozone levels between now and 2018 in their computer model for the DFW air plan to comply with the new, tougher 2008 ozone standard. But 2006 was pre-drought. Although they say they're "adjusting" the meteorology to compensate for weather changes since then, do you really trust TCEQ to assume worst-case weather scenarios when they're still trying to hide the smog impacts of gas pollution from the public? Us either.

So it's with more than a little self-interest that we note a new Stanford study with the too-sexy title of "Occurrence and Persistence of Future Atmospheric Stagnation Events" concluding that the Western US, including Texas, should expect hotter and therefore smoggier summers thanks to climate change. Why? Because hotter temperatures will slow the flow of air around the globe. That means less wind, and less wind means more time for smog-forming chemicals to sit and bake in the hot sun and form harmful levels of ozone. Historically, most of our worst ozone days are when winds are blowing less than 5 mph – stagnate air.

DFW isn't like Denver or LA where mountains form bowls around the urban areas and trap pollution in inversions. But the new study concludes the impact from global warming could have the same effect on the Texas prairie by stagnating air currents:

"Our analysis projects increases in stagnation occurrence that cover 55% of the current global population, with areas of increase affecting ten times more people than areas of decrease. By the late twenty-first century, robust increases of up to 40 days per year are projected throughout the majority of the tropics and subtropics, as well as within isolated mid-latitude regions. Potential impacts over India, Mexico and the western US are particularly acute owing to the intersection of large populations and increases in the persistence of stagnation events, including those of extreme duration. These results indicate that anthropogenic climate change is likely to alter the level of pollutant management required to meet future air quality targets."

And who's more prepared to deal with the "pollution management required to meet future (re: tougher) air quality targets than the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality? Almost any one, including your 13-year old niece who's done so well in 8th grade science this year. Because not only is it the TCEQ's official position that smog isn't all that bad for you, but that there's really no such thing as climate change. It's why you should bring a boatload of skepticism to the computer model that's driving the currently proposed DFW clean air plan. To plug hotter and hotter temps into the DFW smog model for coming years would be admitting to a phenomena that the Rick Perry administration in Austin just can't bring itself to concede. One more example of how the DFW plan is being driven by politics, not science.

As the TCEQ's own staff admitted last week, DFW's ozone levels are often hostage to the weather. If you're model isn't correctly estimating the weather during future ozone seasons, chances are your estimates of future ozone levels will be off as well. But of course, since smog isn't really bad for you there's no downside to being wrong about these things at TCEQ HQ, and only an upside in GOP primaries.

For the rest of us who believe what the science tells us, the consequences are more dire. As the VICE magazine take on the Stanford study said:

"….one reason this study is so important to the climate change conversation—it underlines the public health threat posed by climbing temps. When Obama was touting the EPA's new carbon regulations, he emphasized the public health benefits of drawing down emissions: It would reduce asthma and respiratory illness, he pointed out. But that's largely because shuttering dirty power plants cuts both carbon and particulate pollutants simultaneously; fighting climate change also means fighting asthma.

Now, scientists have demonstrated there's an additional layer of concern to grapple with on the pollution front; climate change is going to begin blocking cities' toxic release valves. If we don't work to slow carbon emissions, these steamier cities will find their streets clogged with stagnant smog. Scrubbing that pollution and finding novel ways to clear the air, too, then, will prove to be a pressing concern in the not-so-distant future.

Highlights from Monday: How the State Hides Gas Industry Pollution

Want to see one example of how low state bureaucrats will stoop to underplay the significance of the impact of oil and gas pollution on DFW air quality? Take a look at some slides that were part of Monday's presentation by Downwinders at Risk's Jim Schermbeck to the regional air planning meeting.

Want to see one example of how low state bureaucrats will stoop to underplay the significance of the impact of oil and gas pollution on DFW air quality? Take a look at some slides that were part of Monday's presentation by Downwinders at Risk's Jim Schermbeck to the regional air planning meeting.

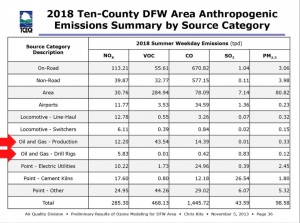

In the first you'll see how the state officially ranks all the "source categories" for human-made, or "Antrhopogenic," smog-forming Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) pollution in North Texas (all the numbers are Tons Per Day):

Yes the pic is fuzzy, (we can land a person on the Moon but can't seem to get charts to show up with a jpeg format online) but if you squint really hard, you'll notice there are two categories for Oil and Gas pollution numbers among the more traditional "Point Sources," Off-Road, "On-Road", etc – "Oil and Gas Production" and "Oil and Gas – Drill Rigs." Looking at these two categories you might think that adding them together would produce total Oil and Gas pollution numbers. You'd be wrong.

As it turns out, there are other Oil and Gas pollution numbers hidden away in other categories in this chart not labeled "Oil and Gas." For example, in both the "Area" and "Point-Other" categories are the numbers for NOx and VOCs pollution from gas compressors. But wait, you object, aren't gas compressors an integral part of any kind of "Oil and Gas Production?" Yes, yes they are. So why aren't they included in that category instead of being stuffed anonymously in these other categories? Great question. Perhaps it has something to do with the volume of pollution they release. Because when you finally wrestle the numbers from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (the TCEQ didn't voluntarily offer this information), compressor pollution turns out to double the amount of smog-forming NOx released from the Oil and Gas industry in the DFW 10-county "non-attainment area." And NOx pollution is what the TCEQ keeps saying is driving our chronic smog problem. Here's the way Schermbeck presented the same TCEQ "source categories" with the compressor numbers now teased out and added to the ones already identified as Oil and Gas:

These additions raise the industry's polluter profile significantly. And that's what this next slide is doing. It's totaling all the Oil and Gas pollution and then re-ranking the categories based on these new numbers. Same totals, just different, and more honest, organization of the individual source figures. Instead of Oil and Gas emissions looking relatively small in relation to other sources like cement kilns and power plants and even locomotives, it escalates the Oil and Gas industry into one of the region's foremost industrial air polluters:

And even this much larger number is still underplaying the total amount of air pollution fracking adds to regional air quality because the state hasn't bothered to try to tease-out the "on-road" pollution that all those fracking waste and water trucks adds to the mix. State air modelers shrugged their shoulders and said they couldn't figure out how on earth to do that. Just by "Googling" the subject, Schermbeck found at least two previous studies that did that very thing – a 2005 Denton report and a 2013 Rand Corporation report that even estimated the amount of dust pollution raised by those trucks.

While those truck totals remain a mystery for now, using the TCEQ's own numbers, compressors make up at least 53% of the total NOx pollution released by the Oil and Gas industry in North Texas, and a full quarter of all VOC pollution released. According to Schermbeck, that's why they make such good targets for electrification, an air pollution control measure he was recommending as part of his larger presentation to the regional air planning committee on Monday.

This is just one example of the kind of duplicitous behavior the state of Texas is resorting to in trying to hide the true environmental and public health impact of the Oil and Gas industry. No slight of hand is too petty. Only by diligent digging by citizens is the truth coming out, ton by ton.

Schembeck's entire (unfuzzy) presentation is now online at the North Central Texas Council of Governments website as part of the June 16th agenda. It loses something without his accompanying narration but the jest of it is easily discerned for those who want to plod through it: TCEQ is doing anything but a sincere job of building a serious clean air plan for DFW. But then again, we bet you already knew that.

Rick Perry, with a Smoking Gun, in the COG Headquarters: Monday at 10 am

The latest chapter in a decades old mystery game of "Get a Clue" happens tomorrow morning, Monday, June 16th when representatives of the Sierra Club and Downwinders at Risk present their case against the current state anti-smog plan during the regional air planning meeting at the headquarters of the North Texas Council of Governments, 616 Six Flags Road in Arlington. Come find out who and/or what keeps the DFW area from ever meeting federal clean air standards year after year and what can be done about it. The meeting starts at 10 am. Citizen groups are expected to do their presentations in the 11 to 12 hour. Then we'll all have a debriefing lunch at the Subway's down the street hosted by State Representative Lon Burnam. Y'all come.

The latest chapter in a decades old mystery game of "Get a Clue" happens tomorrow morning, Monday, June 16th when representatives of the Sierra Club and Downwinders at Risk present their case against the current state anti-smog plan during the regional air planning meeting at the headquarters of the North Texas Council of Governments, 616 Six Flags Road in Arlington. Come find out who and/or what keeps the DFW area from ever meeting federal clean air standards year after year and what can be done about it. The meeting starts at 10 am. Citizen groups are expected to do their presentations in the 11 to 12 hour. Then we'll all have a debriefing lunch at the Subway's down the street hosted by State Representative Lon Burnam. Y'all come.

Sierra Club Sues EPA Over Delayed “Bump Up” for DFW Smog Status

DALLAS, TX – The U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) missed a key deadline in 2013 to classify smog air pollution in Dallas-Fort Worth as ‘severe,’ prompting the Sierra Club to file suit against the agency yesterday afternoon in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia for failing to properly act to protect the health of the people of North Texas.

DALLAS, TX – The U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) missed a key deadline in 2013 to classify smog air pollution in Dallas-Fort Worth as ‘severe,’ prompting the Sierra Club to file suit against the agency yesterday afternoon in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia for failing to properly act to protect the health of the people of North Texas.

The levels of smog in Dallas-Fort Worth are among the highest in the country, and only smoggy California, Houston and Baltimore have levels higher than North Texas. Ozone is the main ingredient in the smog in Dallas-Fort Worth. It triggers asthma attacks in children and is responsible for the red and orange bad air alert days the region sees every year.

“While we recognize that the Environmental Protection Agency has many priorities, nothing is more important than protecting our children from the dangers of smog and the asthma attacks that it can trigger,” said Dr. Neil Carman of the Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club. “The Clean Air Act has mechanisms in place to reduce pollution for areas with long-standing smog problems like Dallas-Fort Worth, but those mechanisms don’t get triggered unless EPA acts.”

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) had a federal deadline to meet the public health standard by 2009, and when the state’s clean air plan failed to reduce pollution levels to meet the protective standards of the Clean Air Act, regulators received an extension to meet the standard by the end of the 2012.

State regulators again failed to develop a plan that would lower smog levels to protect people living in the region. After both failures, the law required EPA to classify Dallas-Fort Worth as having a “severe” ozone problem and publish the notice in the Federal Register in 2013. This action would have required polluters to take additional steps to clean our air. Unfortunately, U.S. EPA missed the deadline, prompting the Sierra Club to file suit late Tuesday, May 20, 2014.

"The Clean Air Act requires polluters to take extra steps in places like Dallas-Fort Worth that have been chronic violators of smog standards," said Jim Schermbeck with Downwinders at Risk, a clean air group based in Dallas-Fort Worth. "But asking Rick Perry to enforce the Clean Air Act in 2014 is like asking Wall Street tycoons to care about low-income families. That's why six million residents need the EPA to do its job and guarantee North Texas safe and legal air."

Because the EPA missed the 2013 deadline to properly classify the Dallas-Fort Worth area as a “severe” ozone smog area, industries are being allowed pollute more than they would otherwise, delaying the protections children, the elderly and people with respiratory illnesses in the region need.

"Today's action is the first step in requiring the EPA to finally solve the ozone problem in D-FW. Too many Texas children end up in the emergency room or miss school because of asthma and other breathing difficulties. We have to hold EPA to its legal requirements to give these families a chance to breathe easier," said Nia Martin-Robinson, Beyond Coal organizer with the Sierra Club in Texas.

Coal-fired power plants across Texas, cement plants in Midlothian and fracking in the Barnett Shale are significant contributors to smog-forming pollution to the region. State regulators have failed to require the most up to date pollution controls on these sources, contributing to the repeated failure of state clean air plans.