With Historic Rebuke, EPA Sends GAF Permit Back to Austin…and a Message to Company

When Janie Cisneros and her Singleton United contingent met with EPA Region Six Director Dr. Earthea Nance and her staff on June 1st, one of the residents’ goals was to convince EPA to send West Dallas asphalt shingle maker GAF’s Title V operating permit back to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality for a rewrite.

Mission accomplished.

In a stunning rebuke that often echoed the sentiments and language used by West Dallas residents campaigning for GAF’s closure, EPA sent notice to the company, state, and residents on late Friday afternoon that not only was the permit deficient, so was the state process that approved it.

The EPA letter is posted on Downwinders’ FaceBook page here.

EPA often gives authority to state agencies to tentatively approve or deny all renewing federal permits in their jurisdiction but retains the right to send the permit back to the agency for reconsideration if it finds the finished product isn’t fulfilling federal regulatory requirements. Even though TCEQ had approved the GAF permit in Austin, it still needed EPA’s approval in Dallas. It didn’t get it.

And the permit didn’t just get sent back. It got sent back with a big ol’ boot print on it. In both tone and scope, EPA’s response is unprecedented.

In its letter EPA identified five major objections, all of them coming down to a different version of the same demand: “TCEQ must ensure that the Title V permit includes monitoring, recordkeeping, and reporting sufficient to assure compliance with the hourly and annual emission limits” GAF has listed in its permit.

Janie Cisneros (l) meets with EPA Regional Administrator Dr. Nance (r) and Staff on June 1st of this year

EPA staffers expose the disconnect between GAF’s estimated permitted emissions and the non-existent, obsolete, or ineffective ways those emissions are accounted for in the permit. This includes the lack of any stack testing on major pollution control equipment in over 14 years at the GAF factory – a major point of contention with residents at their June 1st meeting with EPA.

“It is unclear and the record does not justify how a stack test last conducted 14 years ago during GAF’s normal operations is still representative of current operations….” concludes EPA, and then adds,

“It is unclear to EPA why GAF is not required to conduct periodic stack testing of its thermal oxidizer at a minimum frequency of at least once per permit term (ex. every five years) for VOC, SO2, CO, NOx, PM10, PM2.5 (filterable and condensable), and any relevant Hazardous Air Pollutants. TCEQ must explain how it has determined that the emission characteristics of the Thermal Oxidizer/Waste Heat Boiler have not changed since the latest stack test and are not expected to change over the term of the Proposed Permit. Conversely, if TCEQ believes that the emissions characteristics are reasonably likely to change over time, TCEQ must amend the permit to require periodic stack testing with a specified frequency. Further, TCEQ must amend the Proposed Permit to require the use of the emission factors from the most recent stack test and ensure the calculations used to determine compliance are made part of the permit. “

Because the Proposed Permit does not identify with enough specificity a particular monitoring or recordkeeping requirement associated with the related units, neither the public nor the EPA can ascertain from the permit what monitoring or recordkeeping methodology the source has elected to use, or whether this methodology is sufficient to assure compliance with all applicable requirements. This effectively prevents both the public and the EPA from determining if the chosen monitoring, recordkeeping, and reporting satisfies Clean Air Act requirements.”

Considering how far off the mark the company has historically been in estimating its own pollution to both TCEQ and EPA, this is not an unreasonable requirement. It’s the taking to task of TCEQ’s lack of rigor that’s eye-opening and new.

The majority of EPA’s letter is spent on this kind of combination of surgical/technical explanation of why a permit provision is inadequate, and their slacked-jaw astonishment that TCEQ could approve such a thing.

Team Singleton United at Region 6 EPA HQ on June 1st

But wait, there’s more.

There’s a seven-and-a-half page supplement to the specific Title V comments entitled “Additional Comments Outside of EPA’s Objections.”

As part of this section, EPA does a deep dive into the history of GAF’s nuisance complaints submitted by residents over the last 20 years and concludes “…based on the consistent frequency and nature of odor complaints, nuisance events still appear to be adversely and disparately impacting West Dallas residents’ quality of life and interfering with the normal use and enjoyment of property.” In writing the sentence this way EPA is quoting from the TCEQ’s own definitions of “air pollution” and “nuisance.” With it, EPA has given the City of Dallas just about all the evidence it needs to proceed with amortization.

Clearly exasperated, EPA asks, “Can TCEQ explain what measures, including any associated monitoring, that GAF has implemented that ensures ongoing compliance with the nuisance provisions outlined in 30 TAC § 101.4 or any other information that may provide the EPA and the public certainty that odors leaving the plant are not in violation of nuisance provisions? Has TCEQ been on-site during the heating and unloading of railcars while the “top hatch on the railcar is cracked open” and confirmed whether such unloading operations are a source of emissions/odors at the site? Lastly, complainants and investigators have identified both odors and “smoke” at the site. Has GAF and/or TCEQ considered voluntarily adding new pollution controls and work practice standards to reduce off-site odors as well as SO2 and PM2.5 emissions to minimize potential impacts on the community?”

EPA concludes its letter with advice to TCEQ on how the agency should align its permitting process with modern Environmental Justice metrics and principles. It even gives the state two recommendations: “1) TCEQ should engage early in the permitting process with communities and applicants to address environmental justice, and 2) TCEQ should avail itself of EPA’s most recent EJ resources and tools, such as use of the most up-to-date EJScreen tool and EJ related trainings available.”

It’s clear from the examples and even direct quotes used in the letter that someone at EPA has actually reviewed the blow-by-blow summary of GAF’s 45-year regulatory track record on the Singleton United website as well as its “Case for City Amortization of GAF” – and finds them compelling.

“So Long GAF” postcards on the company’s fenceline May 17th

That’s got to be concerning to GAF management as they continue to try and negotiate their way out of a forced exit by the City. Because as surely as EPA was lecturing the State of Texas in its letter, it was also sending a message to GAF HQ in New Jersey. The message is something like….

“It’s mid-2022 and your Title V permit isn’t even close to being finalized. We’ve challenged TCEQ to make you prove so many things you haven’t wanted to prove in so long that it might take years to work out the kinks – that is, if you really want to. We’re sure we don’t have to remind you that your big, fat, overarching “New Source Review” permit that covers literally everything you’re doing in West Dallas is coming up for renewal in November 2024. That will make this look like a Methodist picnic. Do yourself a favor: work a deal and leave now, while you’re still in control of your own clean-up at a 76-year old factory site.”

We’re paraphrasing of course.

But Texans have never seen an EPA talk to polluters or their facilitators at TCEQ they way it does in this GAF Title V letter. It’s a big and welcomed change. And it was initiated by that group of determined Singleton United/Unidos residents back on June 1st. Congratulations.

Stay Inside. Plant Trees. An Annotated Guide to City of Dallas Air Quality Monitoring

Over the last couple of weeks, the staff responsible for the Air Quality Department at Dallas City Hall’s Office of Environmental Quality have been making the rounds giving presentations about their official air quality monitoring efforts. You can find their complete PowerPoints here as PDFs on the agenda: https://cityofdallas.legistar.com/MeetingDetail.aspx?ID=903849&GUID=B69AEEB6-D5DA-4AE2-B8A4-5BB13C3FD4BE&Options=info|&Search=

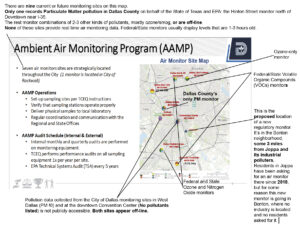

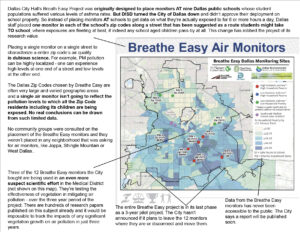

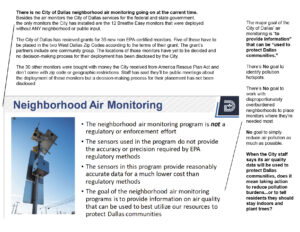

The presentations are divided into two parts. The first deals with the monitors placed in Dallas as part of the State and federal enforcement to monitor DFW’s status as a “non-attainment area” for ozone, or smog. The second is about the “non-regulatory” (i.e not EPA-certified) air monitoring staff has been doing that has up to now has been going on under the “Breathe Easy” banner with a fleet of 12 monitors due to expire this year.

New federal grants have made it possible for the City to buy 35 new “non-regulatory” air monitors of various sizes and capabilities that are aimed at “community monitoring.” By the terms of the grants, five of these have to be placed in two West Dallas zip codes. The other 30 include six larger, more sophisticated air monitors that also come with their own metrological towers and will be placed at the City’s discretion.

This is quite an upgrade for a Department that only a short time ago was dismissing the idea of community monitoring and is in their fourth year of rejecting Joppa residents’ pleas for an air monitor in their neighborhood. That’s the good news.

What’s unclear is how all this new monitoring capability will be used to move the needle of air pollution exposure in Dallas.

Houston has a staff toxicologist that identifies AND advocates for environmental health. Why doesn’t Dallas?

Is the City collecting air quality data so residents can brace themselves on “bad air days”, or are they collecting it to shape City Hall policy that could reduce air pollution and its impacts?

When the goals of all this City air monitoring come up in the new presentations, there’s no mention mention of impacting Dallas City Hall policy. Instead, there are boasts about gathering ““high quality data,” “contributing to local and regional databases,” and “better understanding the performance of low cost sensors” for “public health measures” and “understanding the role air pollution may play in pediatric asthma” (Really? there’s lots of studies already proving this link)

No suggestion for any pro-active City policy to reduce air pollution. No talking point about using the data to address environmental racism or increase City Hall’s much-valued “Equity” in air quality. There’s a lot of emphasis on collecting data but not much attention paid at all to what will be done with that data.

During the Question and Answer session that followed the presentations in front of the Dallas City Council’s Environmental Committee, staff suggested the results of the monitoring could be used to further the City’s air quality goals like…..staying indoors when pollution is bad, and planting trees to mitigate it. Honest.

Dallas City Council Member Jaynie Schultz:

“What are we going to do to reduce air pollution as a result of this data, this incredible trove of information we’re gathering? ….Will you be proposing to Council different things we can do to reduce that asthma so we can actually affect those numbers?

Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability Assistant Director Susan Alvarez:

“We are currently working with our Office of Data Analytics to get that data added to the big data website so it will be publicly available. This is one piece of our grant for the West Dallas project; is to also develop appropriate messaging and to work with a non-profit on that to get that message into some of those schools where we have higher than average pediatric asthma rates….

CM Schutlz: But what’s the message? I’m sorry to interrupt.

Alvarez: The message is related to how to, um, best avoid, um, outside, outdoor activities. The other thing that we’re doing is working with the Texas Trees Foundation on, ah, piloting some interventions using nature based solutions, AKA, trees, and they’re working on that right now. They’re already working on planting vegetative screens”

It’s these kind of circa-1990’s answers that reveal why modern public health expertise is so needed at OEQS and City Hall. And not just included in the mix, buy actually driving City Hall environmental thinking. Data collection without application to policy is the Status Quo.

No OEQS staff holds a public health degree, has done research on the public health effects of air pollution, or is charged with evaluating air pollution levels from a public health perspective. When very high levels of air pollution are picked up by any of these new monitors, OEQS won’t have anyone on staff who’ll have the expertise to tell residents what that means.

Instead, the City will still be making residents do all the heavy lifting of solving problems the City helped create. You’re not only assigning them the task of linking pollution levels to impacts but also making it their responsibility to come up with the answer to cutting that linkage. This is what happened at Shingle Mountain. This is what’s happening in Joppa. This is what’s happening in West Dallas. Despite a fleet of new monitors, the City’s stance seems to be that we’re just collecting the numbers. What people do with them isn’t up to us.

Imagine that being the City’s response to finding levels of toxins in tap water faucets in Dallas neighborhoods. City Hall wouldn’t just publish the information in hopes of residents avoiding drinking the water. City Hall would take action to provide fresh water and eliminate the harm. But for some reason the City feels under no obligation to address toxic air quality in homes the same way.

There are a total of 20 slides in the two presentations. Here’s a brief annotated guide to the four slides that provide the crux of the City’s information:

The City of Dallas’ approach to air pollution in its city limits is reminiscent of the old Community Organizing story about the village that finds abandoned babies floating downstream along its river banks and decides to organize to do something about it. At first there’s only a few, but after a couple of weeks there’s hundreds. Adoption bureaucracies are established. Seal Teams of Baby rescuers are on call 24/7. Special baby dams are built.

Until one day some smartass villager asks: “Why don’t we go upstream to see why the babies are ending up in the river?”

Dallas is always responding after the fact to air pollution problems in a downstream way when residents want them to go upstream and solve the real problems. Problems its often responsible for creating in the first place.

Instrumentation without context and action is pointless. “Neighborhood monitoring” without neighborhood oversight is worthless.

If the City of Dallas wants to maximize the potential of so many new air monitors, it needs real public health expertise to tell residents not just to avoid the danger, but how the danger can be eliminated. And neighborhoods must be driving its monitoring deployment process, not just informed after the fact or consulted on a token basis.

But right now there’s absolutely no process in place at Dallas City Hall to ensure either.

Downwinder Marsha Jackson

Downwinder Amanda Poland

Downwinder Evelyn Mayo

Downwinder Amber Wang

Downwinder Michelle McAdam

Downwinder Satavia Walker

Meet Downwider Cindy Hua

“Forward Dallas” Goes Backwards on Environmental Justice

In many ways the inaugural Forward Dallas “neighborhood summit” on Saturday was a microcosm of the current state of affairs at Dallas City Hall when it comes to Environmental Justice.

For the first three-quarters of the City’s presentation, staff used all the right language in explaining the goals of the once-a-decade, re-imagine-your-neighborhood, citywide land use planning exercise to the approximately 120 registered participants. Primary among them of course was “Equity” – City Hall’s reflexive one-word description of anything it does now days.

But there was also acknowledgement by Interim Director of Planning Julia Ryan that “previous racial inequities” had been ignored and needed to be redressed. Might there be some newfound ambition in this map redrawing to take on the baked-in racist zoning that’s made Southern Dallas the city’s dumping ground?

As it turns out, no. Dallas City Hall still thinks those “previous racial inequities” can be redressed by planting more trees. Honest.

During the last 30 minutes of the “summit,” participants were disbursed to three Zoom “breakout rooms,” one of which promised to focus on the environmental impacts of land use planning.

According to the City of Dallas Plan Department, this was all in your imagination.

If you’ve lived in Dallas the last four years, the Dallas where a six-story illegal “mountain” of shingles has become a national environmental justice symbol, the Dallas where Joppa and other Southern Dallas neighborhoods are constantly fighting off new batch plants, the Dallas that hosts an ancient polluter in West Dallas that appears to be openly flaunting the law. If you lived in this Dallas you might have expected this breakout presentation to include a section, if not base the entire session around, the idea of how to get rid of these kind of “previous racial inequities” that put people dangerously close to industrial polluters.

But City Hall lives in a different Dallas. At least according to this breakout session. One where the most pressing Environmental Justice issues revolve around better water management and planting more trees. According to staff, “heat islands” is THE EJ priority for Southern Dallas.

There was not a single mention of Shingle Mountain, Joppa, or West Dallas. In fact, there was no mention of Dallas’ industrial pollution problems at all. Not a one.

We can’t remember one recent public protest aimed at eliminating heat islands south of the Trinity River. There’s no shortage of trees in Joppa and Floral Farms. Indeed, it’s the City of Dallas lax code enforcement and on-going encouragement of industrial polluters that put the magnificent woods in those neighborhoods at risk.

We can’t remember one recent public protest aimed at eliminating heat islands south of the Trinity River. There’s no shortage of trees in Joppa and Floral Farms. Indeed, it’s the City of Dallas lax code enforcement and on-going encouragement of industrial polluters that put the magnificent woods in those neighborhoods at risk.

On the other hand, since 2018 there have been countless protests, posts, and articles about the problems caused by the City’s continuing embrace of racist zoning, meant to corral “undesirable” people and dirty industries along the Trinity floodplain. Saturday’s session pretended those never happened.

Why? Because City Hall keeps intentionally substituting “Sustainability” for “Environmental Justice.” The two terms aren’t synonymous, though staff uses them as if they were. Sustainability is a catch-all term usually paired, as it was on Saturday, with traditional conservation concerns like water management and urban forestry. A lot of mainstream green groups use it to update those concerns in light of the Climate Crisis. Nothing wrong with that. But it isn’t on point when it comes to the urgency of vastly unequal pollution exposure burdens currently suffered by Black and Brown residents.

Environmental Justice is inherently about those unequal pollution burdens, they’re not tangential to any other goals. And driving those unequal pollution burdens in Dallas is racist zoning that puts the most polluting industries in predominately Black and Brown neighborhoods. To host a session on the environmental impacts of land use planning and not mention this fact even once is like holding a symposium on the Afghanistan War and never mentioning 9/11.

When this absence was noted in the Question and Answer part of the breakout session, staff were quick to assert how “really important” and “extremely important” the topic of “buffer zones and those kinds of thing” were to them and the process.

So important they never talked about it until they were forced to. This is a very bad sign.

So important they never talked about it until they were forced to. This is a very bad sign.

Staff didn’t even have the courage to quote the specific charge given to the Forward Dallas process by the much ballyhooed Climate Plan. There it is, listed as goal #4 under Air Quality:

The City will review and potentially amend its zoning standards to separate residential and industrial uses. In addition, it may also consider buffer zones between industrial uses and residential or recreational areas to protect residents from harmful emissions and hazardous industrial activities. The City should evaluate the appropriate buffer distances for air quality and industry types.

Every other air quality goal from the CECAP, including ones with a lot less overlap with land use, were reviewed. This one, directly on point, was ignored.

The most generous interpretation is that the Planning staff may want to sincerely try to resolve EJ issues but feel they lack the expertise, and default to relying on OEQS (Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability) (¯\_(ツ)_/¯). This is an even worse sign.

Despite neighborhood opposition, OEQS has given its OK to every batch plant recently proposed for Southern Dallas, paid more attention to water run-off issues than human health effects at Shingle Mountain, and refused air monitoring requests from Joppa residents. OEQS has no one on staff with public health expertise or experience. It has been part of the problem Forward Dallas is supposed to be solving.

Marsha Jackson fighting off batch plants recommended by the OEQS.

When this was pointed out in the Q&A, OEQS staffer Suzanne Alvarez defended her own and her peers’ experience with “environmental remediation.” Remediation is the term regulators use for cleaning-up environmental problems after the fact, and is usually applied to soil and water contamination. It has nothing to do with measuring or anticipating human health harms from land use based on a public health perspective.

Alvarez’ own degree is in Civil Engineering and includes no public or environmental education at all. She’s not alone. OEQS is heavy on engineers and absent of any public health expertise. So the Department’s answer to every problem is also engineering heavy and absent any public health insight except to say whether a specific monitor is meeting federal standards or not. You’ll never get a comprehensive or honest Environmental Justice evaluation or prescription from such a group. The failure is baked-in.

This is why it’s a fatal mistake to let OEQS take the lead on this subject within Forward Dallas. If you want to change the Status Quo, you have to have someone other than the folks in charge of the Status Quo to do it.

One of the best examples of a public health perspective being integrated into local government policy in Texas is in Houston.

Dr. Loren Hopkins (fourth from right) is a City of Houston employee dedicated to environmental health.

Dr. Loren Hopkins is the Chief Environmental Science Officer for the Houston Health Department. Dr. Hopkins has served on the U.S. EPA Science Advisory Board and Risk and Technology Review Methods Panel and been a visiting scientist on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Air Pollution and Respiratory Health Branch, Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects, National Center for Environmental Health in Atlanta, Georgia. Since 1998, she’s conducted research on the human health effects of Houston’s air pollution.

Rather than a purely reactive mode, Dr. Hopkins has been a proactive environmental health and justice advocate. Here’s an excerpt from a Houston Chronicle article about a neighborhood batch plant fight:

“Echoing the community’s health concerns about the fine particulate pollution emitted by concrete batch plants, the City of Houston’s Chief Environmental Science Officer, Dr. Loren Hopkins, shared data showing that the Acres Homes community already suffers six times the rate of ambulance-treated asthma attacks and twice the rate of cardiac arrests compared to the rest of Houston. Those health impacts are directly associated with exposure to fine particulate pollution, which is compounded by the multiple concrete batch plants already existing in Acres Homes.”

Can you imagine any staffer from the OEQS saying the same thing about a batch plant in Southern Dallas? Houston has public health advocates who oppose new polluters in communities of Color. Dallas has engineers who approve them.

If Planning staff really want to use the Forward Dallas process to tackle the systematic environmental justice issues driving so much grassroots discontent in the city, it needs to rely more on public health professionals like Dr. Hopkins and less on the engineers at OEQS.