Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals Linked to Endometriosis

Another example of the insidious nature of endocrine disrupting chemicals is out.

Another example of the insidious nature of endocrine disrupting chemicals is out.

This week saw the publication of a study from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Maryland that shows an association between women with higher levels of a estrogen-mimicking pesticide and increased incidence of endometriosis.

Women were divided into groups with pelvic pain and no symptoms. Those with pain were more likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis if they had high blood levels of the estrogen-like pesticide hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH). Although HCH has been banned as a crop pesticide in the United States, it builds up and persists in the environment, so it remains in some food supplies.

Women with the highest blood of a sunscreen chemical, benzophenone, in their urine also had a higher risk of endometriosis according to the study, published in Environmental Science and Technology.

“Our studies are beginning to corroborate the idea that environmental estrogen may be associated with endometriosis,” said the Institute's Director Germaine Buck-Louis. But the link has a long toxicological history.

In 1993, the connection between endometriosis and environmental chemicals was discovered when Rhesus monkeys fed food contaminated with dioxins – hormone-disrupting pollutants created by waste incinerators and other industries – developed endometriosis 10 years later. (The Midlothian cement plants and the Exide lead smelter in Frisco have been the the largest industrial sources of airborne dioxin in North Texas over the last decade.)

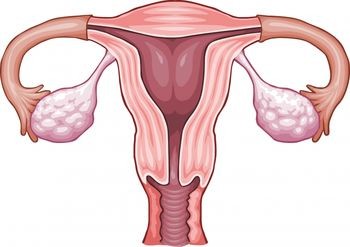

A 2009 Italian study linked the disease, which stimulates uterine tissue growth in the ovaries or other parts of the body, to PCB and DDT exposure. Both are endocrine disrupters

“It’s certainly plausible that any outside source that alters estrogen levels, even slightly, could contribute to gynecological diseases,” said Dr. Megan Schwarzman, a family physician at San Francisco General Hospital and an environmental health scientist at the University of California, Berkeley who was not connected directly with the Institute study.

With 80,000 chemicals and counting in the marketplace to be exposed to, it's more than plausible.