Stay Inside. Plant Trees. An Annotated Guide to City of Dallas Air Quality Monitoring

Over the last couple of weeks, the staff responsible for the Air Quality Department at Dallas City Hall’s Office of Environmental Quality have been making the rounds giving presentations about their official air quality monitoring efforts. You can find their complete PowerPoints here as PDFs on the agenda: https://cityofdallas.legistar.com/MeetingDetail.aspx?ID=903849&GUID=B69AEEB6-D5DA-4AE2-B8A4-5BB13C3FD4BE&Options=info|&Search=

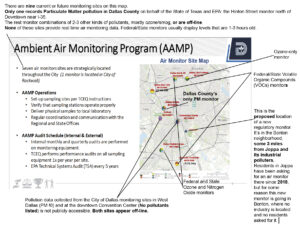

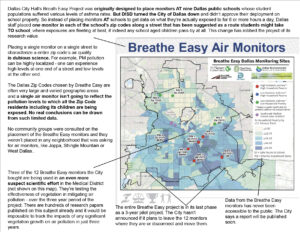

The presentations are divided into two parts. The first deals with the monitors placed in Dallas as part of the State and federal enforcement to monitor DFW’s status as a “non-attainment area” for ozone, or smog. The second is about the “non-regulatory” (i.e not EPA-certified) air monitoring staff has been doing that has up to now has been going on under the “Breathe Easy” banner with a fleet of 12 monitors due to expire this year.

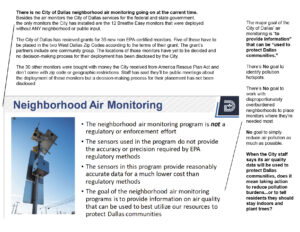

New federal grants have made it possible for the City to buy 35 new “non-regulatory” air monitors of various sizes and capabilities that are aimed at “community monitoring.” By the terms of the grants, five of these have to be placed in two West Dallas zip codes. The other 30 include six larger, more sophisticated air monitors that also come with their own metrological towers and will be placed at the City’s discretion.

This is quite an upgrade for a Department that only a short time ago was dismissing the idea of community monitoring and is in their fourth year of rejecting Joppa residents’ pleas for an air monitor in their neighborhood. That’s the good news.

What’s unclear is how all this new monitoring capability will be used to move the needle of air pollution exposure in Dallas.

Houston has a staff toxicologist that identifies AND advocates for environmental health. Why doesn’t Dallas?

Is the City collecting air quality data so residents can brace themselves on “bad air days”, or are they collecting it to shape City Hall policy that could reduce air pollution and its impacts?

When the goals of all this City air monitoring come up in the new presentations, there’s no mention mention of impacting Dallas City Hall policy. Instead, there are boasts about gathering ““high quality data,” “contributing to local and regional databases,” and “better understanding the performance of low cost sensors” for “public health measures” and “understanding the role air pollution may play in pediatric asthma” (Really? there’s lots of studies already proving this link)

No suggestion for any pro-active City policy to reduce air pollution. No talking point about using the data to address environmental racism or increase City Hall’s much-valued “Equity” in air quality. There’s a lot of emphasis on collecting data but not much attention paid at all to what will be done with that data.

During the Question and Answer session that followed the presentations in front of the Dallas City Council’s Environmental Committee, staff suggested the results of the monitoring could be used to further the City’s air quality goals like…..staying indoors when pollution is bad, and planting trees to mitigate it. Honest.

Dallas City Council Member Jaynie Schultz:

“What are we going to do to reduce air pollution as a result of this data, this incredible trove of information we’re gathering? ….Will you be proposing to Council different things we can do to reduce that asthma so we can actually affect those numbers?

Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability Assistant Director Susan Alvarez:

“We are currently working with our Office of Data Analytics to get that data added to the big data website so it will be publicly available. This is one piece of our grant for the West Dallas project; is to also develop appropriate messaging and to work with a non-profit on that to get that message into some of those schools where we have higher than average pediatric asthma rates….

CM Schutlz: But what’s the message? I’m sorry to interrupt.

Alvarez: The message is related to how to, um, best avoid, um, outside, outdoor activities. The other thing that we’re doing is working with the Texas Trees Foundation on, ah, piloting some interventions using nature based solutions, AKA, trees, and they’re working on that right now. They’re already working on planting vegetative screens”

It’s these kind of circa-1990’s answers that reveal why modern public health expertise is so needed at OEQS and City Hall. And not just included in the mix, buy actually driving City Hall environmental thinking. Data collection without application to policy is the Status Quo.

No OEQS staff holds a public health degree, has done research on the public health effects of air pollution, or is charged with evaluating air pollution levels from a public health perspective. When very high levels of air pollution are picked up by any of these new monitors, OEQS won’t have anyone on staff who’ll have the expertise to tell residents what that means.

Instead, the City will still be making residents do all the heavy lifting of solving problems the City helped create. You’re not only assigning them the task of linking pollution levels to impacts but also making it their responsibility to come up with the answer to cutting that linkage. This is what happened at Shingle Mountain. This is what’s happening in Joppa. This is what’s happening in West Dallas. Despite a fleet of new monitors, the City’s stance seems to be that we’re just collecting the numbers. What people do with them isn’t up to us.

Imagine that being the City’s response to finding levels of toxins in tap water faucets in Dallas neighborhoods. City Hall wouldn’t just publish the information in hopes of residents avoiding drinking the water. City Hall would take action to provide fresh water and eliminate the harm. But for some reason the City feels under no obligation to address toxic air quality in homes the same way.

There are a total of 20 slides in the two presentations. Here’s a brief annotated guide to the four slides that provide the crux of the City’s information:

The City of Dallas’ approach to air pollution in its city limits is reminiscent of the old Community Organizing story about the village that finds abandoned babies floating downstream along its river banks and decides to organize to do something about it. At first there’s only a few, but after a couple of weeks there’s hundreds. Adoption bureaucracies are established. Seal Teams of Baby rescuers are on call 24/7. Special baby dams are built.

Until one day some smartass villager asks: “Why don’t we go upstream to see why the babies are ending up in the river?”

Dallas is always responding after the fact to air pollution problems in a downstream way when residents want them to go upstream and solve the real problems. Problems its often responsible for creating in the first place.

Instrumentation without context and action is pointless. “Neighborhood monitoring” without neighborhood oversight is worthless.

If the City of Dallas wants to maximize the potential of so many new air monitors, it needs real public health expertise to tell residents not just to avoid the danger, but how the danger can be eliminated. And neighborhoods must be driving its monitoring deployment process, not just informed after the fact or consulted on a token basis.

But right now there’s absolutely no process in place at Dallas City Hall to ensure either.