EPA Pushes Back Against Low-Dose Testing of Endocrine Disrupters

Responding to a report last year that concluded the way EPA tests for harm from hormone-wrecking chemicals is out-of-date, the Agency itself published a review of its methodology last week that, not surprisingly, vindicated current practices.

Responding to a report last year that concluded the way EPA tests for harm from hormone-wrecking chemicals is out-of-date, the Agency itself published a review of its methodology last week that, not surprisingly, vindicated current practices.

In its annual "State of the Science" report, the EPA said that non-linear effects from exposure to endocrine disrupters have been documented, but concluded they were "rare" and did not constitute enough evidence to change the way the Agency assess toxic health harms.

“There currently is no reproducible evidence” that the low-dose effects seen in lab tests “are predictive of adverse outcomes that may be seen in humans or wildlife populations for estrogen, androgen or thyroid endpoints,” the agency report said. “Therefore, current testing strategies are unlikely to mischaracterize…a chemical that has the potential for adverse perturbations of the estrogen, androgen or thyroid pathways.”

Written by EPA officials with input from a team of scientists and managers from the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Institute of Child Health and Development, the draft was signed by Robert Kavlock, the EPA’s Deputy Assistant Administrator for Science.

Laura Vandenberg, the Tufts University researcher who headed up last year's study, "Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses", responded by saying EPA's acknowledgement of endocrine disruption is a step forward, but added that the Agency had made some “odd, and possibly political decisions” in the new report.

"(The EPA's conclusions) fly in the face of our knowledge of how hormones work. They [endocrine disrupting chemicals] are overtly toxic at high doses but act like hormones, with completely different actions, at low doses.”

Vandenberg said the EPA used out-of-date studies on atrazine, when they should have used a new publication with dozens of authors from around the world showing the “consistent, low-dose effects of this chemical on amphibians, reptiles, fish, birds and mammals.”

Downwinders know that they are the recipients of low-level doses of hundreds, if not thousands of different chemicals trespassing into their lungs. They know that constant exposure to these chemicals, even at "safe levels" is harming them and their families. There are no computer models that can adequately reproduce what it's like to breath the air downwind of a waste-burning cement plant, a compressor station, or a trailer park masquerading as a lead smelter. Things happen on a molecular level that we are only now beginning to understand because we had no knowledge of the physiology of hormones or DNA when the toxicity tests EPA still uses were first imagined. Small stuff adds up.

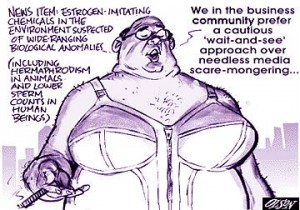

But EPA is loath to admit this because it would mean turning the regulatory world upside down. If there are no "safe levels," there is no status quo. The system depends on the premise, however obsolete, that little bits of poison over a long period of time won't hurt most of us. It's this premise that Vendenberg and her colleagues were aiming at last year and it's this premise that EPA is defending in this newest report.